Jabil Prepares for Production AM: It’s Down to the Basics Now

Jabil is getting ready for additive manufacturing to take its place as a production option in addition to conventional processes such as molding and machining. AM can and will fill this role, the company says — the focus now is on controlling cost and assuring quality and reliability.

For additive manufacturing (AM) to be truly interesting, it has to succeed in ways that are boring. That is, it has to compete on cost against other processes, it has to operate within defined quality standards, and it has to be a reliable option for day-to-day production. If it can do these things, then some of the most compelling promises of AM become attainable, including distributed manufacturing and manufacturing on demand. Manufacturing solutions provider Jabil expects to realize these promises soon. To do so, it is working on getting the boring details right.

HP Multi Jet Fusion 3D printers in the new additive manufacturing area of Jabil’s Auburn Hills, Michigan, plant.

“AM will be transformative,” says Tim DeRosett, director of product management with the company’s additive group. “It’s just a question of what the timeframe will be.” And the matter is urgent because there is increasing reason to believe the timeframe might be short. In terms of polymer parts, the company’s focus today, AM technology is ready for production right now.

DeRosett was my host during a visit to Jabil’s production facility in Auburn Hills, Michigan. A new additive manufacturing area at this facility currently includes three HP Multi Jet Fusion machines and one EOS machine for selective laser sintering, all intended for production parts. The room they occupy offers space for more than double this number of machines, and DeRosett says more production AM equipment will be added here before the end of the year. Previously, the Auburn Hills facility has been strictly for assembly, essentially without part-making capacity located here, but now AM will be in a position to allow assembly to operate economically in ways it never could. Molded or machined components were made somewhere else and shipped here. They were unloaded here, stored here and inventoried here until needed. Now, increasingly, in the cases of many components, 3D printing will be able to produce them as they are needed — taking the place of storage, taking the place of inventory. The supply chain will get that much simpler, adding to the benefits AM also brings in terms of design flexibility and subassembly consolidation.

The Auburn Hills plant previously had no part-making capacity; it was strictly for assembly. AM will change that. The room offers space for more machines, and it’s expected that more production AM equipment will be added here.

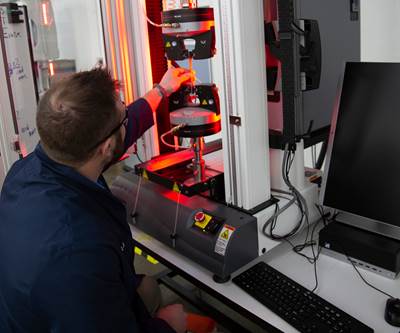

But the considerations right now focus on assuring quality, DeRosett notes — delivering the same consistency in 3D printing that all the other lines and processes at Auburn Hills already deliver. During my visit, this is the work I saw the Jabil personnel performing: the repetitive but vital work of printing and evaluating test pieces to validate the AM machines’ capabilities within the facility’s ISO 13485-certified quality system. The considerations right now also include controlling cost and assuring reliability. And in large part, Jabil is addressing these considerations through a special new facility opened in another state — more on this below.

But first, what is Jabil?

Major Manufacturer

Jabil generally needs to be introduced, because the company typically performs an unsung role in the service of other companies that are much better known. With over 200,000 employees across 100 facilities in 26 countries, Jabil is in fact quite likely the biggest company most people have never heard of — by one account the third-largest contract manufacturer in the world. It makes the products that brand-name OEM companies develop and market, and the facility in Auburn Hills is focused on performing this role for medical equipment. The identities of customers and their products are among the details Jabil asked me to guard, but to tour the Auburn Hills facility is to see (it can’t be missed) one well-known medical industry brand in particular held high, because serving this company is the reason for a large share of the facility’s current activity.

Yet medical was not always the focus here. Located near Detroit, this facility once served the automotive industry, finding a new industry focus only near the start of the previous decade as automakers shifted significant amounts of production away from the U.S. But now, with additive manufacturing, DeRosett sees it as likely that automotive work can be brought back. Distributed and on-demand manufacturing — that is, the chance to easily make parts precisely where they are needed and when they are needed — offer costs savings that are easily competitive with any advantage in sending work far away.

And this hope is not just speculative. Urging from customers in the automotive and heavy equipment industries led Jabil to invest in AM capacity. The demand from these customers for 3D printed parts provided the basis for Jabil to set up the new capacity within an existing assembly facility where 3D printing might also be able to — in some cases — replace injection molding or machining to realize an entirely different, more streamlined supply chain.

Take Its Place

But “replace” is not really the aim, or not the full aim. Jabil runs something like 15,000 CNC machine tools and 4,000 injection molding presses. Rather than replace, the company’s vision for AM is that it will take its place alongside other processes. Taking its place will mean expanding production opportunities by enabling some products and some components that might never have been possible without AM. But it will also mean taking on a share of work that today is an awkward fit for those other, established processes.

One example is plastic parts that today are overly expensive because their unit volumes do not justify mold tooling. Parts with these low quantities are a common characteristic of medical devices, which frequently serve a narrow market. Another example is systems for which assembly cost is high, where subassemblies might be replaced with single 3D printed pieces.

One important—and underappreciated—opportunity for AM will be inexpensive and even mundane parts.

But one other important opportunity for AM will be inexpensive and even mundane parts, DeRosett says. This opportunity is underappreciated. In medical devices, there are many components that are expected to be cheap and need to be cheap. And frequently, compromises are made in order to keep the cost very low.

Wheel sets illustrate this, he says. A product designer might accept off-the-shelf wheels just to save cost, whereas 3D printing might now make it economical to produce tailored wheel sets that are better for the product. Ducting is another detail offering this opportunity. Molding is a design-limiting process for producing ducts, but 3D printing can produce ducts that are both cost-competitive and precisely adapted to the overall product design.

Distributed manufacturing is the other possibility AM realizes, he notes. Other part-making processes require hard tooling to be moved before production can be moved, which effectively means production is rooted in place. But with AM, all that needs to be relocated is a digital file. Jabil currently performs production in San Jose and Singapore on AM machines like those in Auburn Hills, and team members in all these locations have views into available AM capacity at all these sites. Production can be shifted digitally between sites and across borders instantaneously according to the location of not only machine availability, but also the location of demand, in search of reduction in shipping costs to the final destination.

Material Advantage

Indeed, for AM to operate in production is to operate in a mode of continually optimizing cost. DeRosett says Jabil sees four big cost components in the way it thinks about production economics overall: machine, facility, labor and materials. With AM, one of those cost areas in particular has been in the company’s sights — and it isn’t any of the first three.

He says, “In terms of the cost of the machine, the scale of what we hope to do with additive will give us buying power. The facility cost is fixed, but there are things we can do internally to continue to run leaner and more efficiently. And labor cost is locally determined.” But materials cost in additive manufacturing is still company-dependent. Therefore, Jabil has chosen to be the company on which the cost depends. To support AM — to support the full extent of its aims for AM — Jabil has created a new materials development facility for additive manufacturing in Chaska, Minnesota.

Here are three problems the company sees with AM materials right now: (1) There are not enough options in 3D printing materials on the market to meet the needs of customers accustomed to the material range of injection molding; (2) material prices in AM are artificially high because of limited sourcing; and (3) the same limited sourcing results in a supply that might not reliably support production once Jabil fully scales up. Jabil’s new materials facility aims to answer all three challenges. New AM materials are being developed here to meet customer application needs, which Jabil, as the owner of the materials created, is then in a position to see into production at scales the company is likely to need.

There is a lot more to say. The materials facility is so important to what Jabil hopes to do in applying additive manufacturing to production that in order to understand the company’s hopes for AM, the Additive Manufacturing media team visited Chaska first. Read our report after we were given the first look at this new facility.

3D Printing’s Preview

For Jabil, when it comes to AM, there are no major questions anymore. That additive will have a place in production is clear. It solves too many problems not to. It offers too many efficiencies not to. Instead, just the small questions need to be answered now. The fundamentals need to be addressed for AM to realize its promise, and Jabil is addressing them this year. By next year, production AM ought to be established and routine.

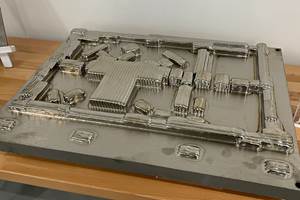

Additive manufacturing at the Auburn Hills plant began with tooling. These nine small 3D printers are still used to engineer and produce custom tooling within the facility.

I mentioned earlier that the Auburn Hills facility previously had no part-making capability. That is not quite true. For a over a year now, one of the resources in this facility has been a rack of nine desktop-size Ultimaker 3D printers used to make assembly jigs and other custom-engineered tooling for use within the plant. In the past, tooling such as this was made by vendors. The work was farmed out to local tool shops, with the distance and delay making tooling difficult to refine. But once the tool-making capacity came in-house thanks to 3D printing, custom tooling could be made with much less compromise. The originators of new tools now work to engineer precisely the tools that bring the most efficient use, and they use quick builds to iterate quickly through various designs to get to optimal solutions. Thanks to on-site 3D printing capability, tooling development now proceeds more rapidly, tooling designs have improved, tooling can now be obtained as needed, and the cost of tooling has gone down. This is how AM played out in a small-scale application in this facility, simply making tools. Now that AM will make full-scale production parts at this same facility, the expectation is that this work will also see these same advantages.

More on Additive Manufacturing for Production at Jabil

What does Jabil plan to do with these materials? What kinds of production AM will take place? And where is all this headed? Find more of our reporting at gbm.media/jabil.

Related Content

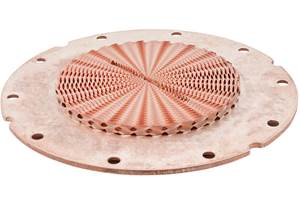

With Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM), Cooling Technology Is Advancing by Degrees

San Diego-based Fabric8Labs is applying electroplating chemistries and DLP-style machines to 3D print cold plates for the semiconductor industry in pure copper. These complex geometries combined with the rise of liquid cooling systems promise significant improvements for thermal management.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreWhat Is Neighborhood 91?

With its first building completely occupied, the N91 campus is on its way to becoming an end-to-end ecosystem for production additive manufacturing. Updates from the Pittsburgh initiative.

Read More3D Printed Titanium Replaces Aluminum for Unmanned Aircraft Wing Splice: The Cool Parts Show #72

Rapid Plasma Deposition produces the near-net-shape preform for a newly designed wing splice for remotely piloted aircraft from General Atomics. The Cool Parts Show visits Norsk Titanium, where this part is made.

Read MoreRead Next

AM at Jabil: From 3D Printing Materials to Distributed Manufacturing

One of the largest manufacturers in the world has made a significant investment in 3D printing — both as a user and an advancer of this technology. Our original reporting dives into the what and why of additive manufacturing at Jabil.

Read MoreJabil’s Additive Materials Innovation Center: First Look

Additive Manufacturing Media was the first press to tour the Chaska, Minnesota, facility originally intended to be a clandestine additive manufacturing (AM) materials lab. What this capacity means for Jabil and 3D printing users.

Read MoreHow to Implement Additive Manufacturing Across a Global Company: 5 Lessons

With more than 100 facilities and about 200,000 employees worldwide, Flex has a steep challenge in bringing 3D printing into its operations. Five things the company is learning.

Read More