7 Takeaways on 3D Printing As a Pathway to Polymer’s Future

The Cleveland section of SPE hosted “Additive Manufacturing: Printing the Path for the Future” on October 17, 2024. Speakers signaled where AM is and where it is headed with session topics ranging from pellet-based 3D printing to qualification and commercialization of additively manufactured products.

Share

3D printing technology companies, additive manufacturing users and educators, and plastics professionals interested in AM gathered Thursday, October 17, 2024, for a one-day conference organized by SPE’s Cleveland section. Titled “Additive Manufacturing: Printing the Path to the Future,” the event covered a range of polymer 3D printing technologies, materials and applications.

I attended the event as a panel moderator and member of the media. Despite being a regional event attended mostly by professionals from Cleveland and the surrounding area, the conference offered a snapshot of successes and remaining challenges with 3D printing in plastics. (Although there was some mention of metal 3D printing for tooling, the content of the presentations focused primarily on the use of polymer-based printing for direct production of plastic parts or tooling). Here are seven takeaways from the event:

1. Pellet printing is on the rise.

Speakers from Arburg, 3D Systems, JuggerBot 3D and Additive Engineering Solutions (AES) covered 3D printing technologies that use extrusion, but all four focused on those that extrude feedstock supplied in pellet format. For Arburg’s Freeformer platform, this material choice was a natural one; as a manufacturer of injection molding presses, the company wanted to see if it could “print with the same material and similar technology” to injection molding, shared Sean Dsilva, Arburg USA AM manager. Users of this platform appreciate the availability of familiar injection molding materials on this printer, making new printed parts easier to qualify. Zac DiVencenzo, president and co-founder of JuggerBot, echoed that sentiment, sharing the company’s pivot from filament to pellet-based fused granulate fabrication (FGF) because of customer expectations to work with familiar materials.

Stump shared this case study in which the pellet-based Titan technology was used to manufacture a thermoforming mold for an RV fender skirt. Printing the part with an open fill structure negated the need to drill vacuum holes in the mold, and pellet extrusion enabled the tool to be completed in just 15 hours.

But for larger printers such as 3D Systems’ Titan platform and JuggerBot’s family of machines, pellets offer many practical advantages. “Injection molding pellets are as cheap as it gets,” for 3D printing material, said Haley Stump from 3D Systems, highlighting several case studies in which pellet material was used to save up to two-thirds the cost of filament to build the same geometry. She also shared the flexibility of pellets in two senses — flexible materials are difficult to print with filaments, but much easier to extrude from pellets, and “The sky’s the limit,” as far as material choice when 3D printing users have the flexibility to choose pellets. DiVencenzo also pointed out higher extrusion rates possible with pellets over filament, which can have impact on productivity and throughput.

2. Functional materials (regardless of format) are in growing demand.

Greg Constantino, senior materials and application development specialists at Stratasys, spoke about resin materials for the company’s Origin platform, citing rising demands for specialty materials like those rated for flame resistance and electrostatic dissipative (ESD) properties. But introducing new materials can be in vain if they can’t be qualified. “They’re not going to decrease the specification requirements just because it’s additive,” Constantino said, calling for AM users and material suppliers alike to embrace existing specifications such as SAE J2527, an automotive standard that is now being used by additive manufacturers in other industries such as electronics enclosures and outdoor furniture.

3. Process control is mandatory.

Speakers spoke candidly about challenges with polymer 3D printing, and how they or their customers are overcoming these issues. JuggerBot’s DiVencenzo emphasized the importance of material handling before feedstock even reaches the printer: “There is no true control without proper moisture in the material,” he said, calling for material drying as an initial step in the production process.

The robot-based 3D printer at AES. The company has learned that printing at large scale can reveal problems not seen in extrusion of smaller components.

Andrew Bader of AES shared challenges with large format additive manufacturing (LFAM), which the company performs on both gantry-style and robot-driven systems. A primary lesson for AES has been understanding thermal management at scale. “The stakes in large format are pretty big,” Bader said, describing how scale exacerbates potential problems that may go unexpressed at a smaller print size. “Maybe you printed something at 2 feet and it was fine, but it doesn’t print the same at 10 feet.”

Other speakers dug into the specifics of qualifying and maintaining an additive manufacturing process in polymers. Tracy Albers, president and CTO of RP+M, described how the contract manufacturer has become a qualified supplier of FDM-printed aerospace parts for Boeing through extreme process control. “Every time I replace a major component of a printer, I have to requalify that machine,” she said, making the point that this is a reality of production AM for critical parts in a regulated industry. “AM is inherently variable,” she stated, but this is not necessarily a weakness — simply a reality that manufacturers must accept to produce critical qualified parts.

4. The promise of multimaterial 3D printing continues to grow.

Arburg’s platform supports combining multiple materials such as this clip which uses rigid PC/ABS for the body and flexible TPU for the jaws. (Another potential advantage from pellets: more homogenous parts.)

Dsilva showed several examples of multimaterial prints made with Arburg’s Freeformer, which can support up to three processing units for material jetting. One is typically reserved for support material, but many users choose to apply rigid and flexible materials with the remaining two, producing parts such as robot grippers or handles in an overmolding fashion.

Michael Ponting, chief science officer of Peak Nano Systems, shared his company’s process for 3D printing lenses by layering nanofilms in a precise sequence; the company has created a catalog of refractive index properties for these films, which it also produces, and can create lenses that are lighter weight and more compact than traditional lens production processes. The films are thermoformed together, and then cut into lens shapes and optionally turned or molded to produce three-dimensional shapes. The layer-based technique allows for precise tuning of lens properties, as well as the production of lenses with a consistent refractive index across the entire volume, something not possible to achieve through injection molding.

5. High-touch applications are ripe for 3D printing adoption.

Peter Jung of PPG described the company’s Ambient Reactive Extrusion or ARE technology, which uses two-component chemistries to 3D print polymer parts that cure at room temperature, without melting. The process is particularly suited to flat designs and simple geometries in flexible materials. One early application is producing seals and gaskets for Lockheed Martin aircraft; in the past, technicians mixed sealant and applied it by hand in a process that could take multiple shifts to complete. Now, PPG manufactures these seals using ARE, reducing the cost of the seals by 30% and the installation time by 90%.

But even less critical parts can benefit from the automation and repeatability of a 3D printing process; Stump for instance shared how Titan printers have been used to produce patterns and end-use mannequins for display, items that are very often sculpted by hand.

6. Commercialization is happening.

Owen Timlin of BASF Forward AM told the story of the Orbit X Pro football helmet, developed with 3D printed lattices for padding. The helmet is now on the market and being used by NFL players, including Nick Chubb of the Cleveland Browns.

Alongside candid discussion about ongoing material development and technology challenges, many speakers shared real examples of products that have gone to market with 3D printed polymers. Notably, Owen Timlin of BASF Forward AM told the story of the development of a new NFL helmet that uses 3D printed lattices produced with one of the company’s polymer powders through Multi Jet Fusion. BASF and helmet company Xenith were partners in 2019’s NFL Helmet Challenge Symposium and awarded funding for their initial concept; the product that resulted, the Orbit X Pro, is now available and even in use by some professional athletes this season. Other 3D printed products described throughout the event include seats for the Boeing Starliner printed by RP+M, night vision goggles using lenses manufactured by Peak Nano Systems, furniture produced on Titan printers, the ARE seals described above and more.

While there may always be a tipping point between polymer 3D printing and injection molding, Greg Pugh of Crown Equipment pointed out that the quantity at which that switch should happen is increasing. Nicki Gear of The Technology House pushed for manufacturers to consider tooling cost and part design as well as quantities in making an initial production decision. “Injection molding is not a cheap process,” she pointed out. “You might get cheap parts, but it’s not a cheap process,” which may indicate additive manufacturing as a better option.

7. Collaboration is key.

Many speakers pushed for more open conversations between AM users and technology and material suppliers. Gear argued for letting users get free of “painful” service agreements on their equipment and better bulk pricing from material manufacturers. On the supplier side, Dana McCallum, vice president of North American sales for Xact Metal, welcomed this, saying that open conversations with customers give OEMs grounds to discuss pain points internally and with their own supply chains to work toward solutions.

I moderated a conversation during the event focused on AM adoption and resources for Northeast Ohio manufacturers. From left to right: Me, Stephanie Gaffney (Youngstown Business Incubator), Ben DiMarco (America Makes), Steve Fritsch (Team NEO) and Mike O’Donnell (MAGNET). Photo: Susan Montgomery, SPE

On the panel which I moderated focused on AM resources for Ohio manufacturers, speakers encouraged audience members to reach out to local and national manufacturing organizations (including those represented on stage: America Makes, MAGNET, Team NEO and the Youngstown Business Incubator or YBI) early in their journeys for guidance, training and funding. Stephanie Gaffney, director of advanced manufacturing programs for the YBI, pointed out that many of these organizations have their own 3D printers and can even provide test parts and other services as manufacturers explore their options. Panelists also encouraged early users to tap into the existing supply chain and use external service providers for 3D printed parts to build a business case before adopting the technology internally.

Taken as a whole, the event offered a realistic picture of additive manufacturing in plastics, including both its successes and ongoing challenges. But speakers were optimistic about the technology’s growth potential as a manufacturing method. David Tucker of ImplementAM described a trajectory for additive in which its current status as an “enabling technology” will give way to making it a “background technology” that goes virtually unnoticed because it has reached such a level of ubiquity that manufacturers can take it for granted.

Related Content

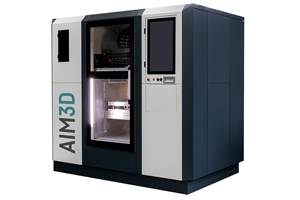

AIM3D Study Shows 3D Printing Ultem 9085 Pellets Offers Lower Cost, Higher Tensile Strength

The material qualification testing indicates many benefits of creating components with AIM3D’s ExAM 510 printer using the composite extrusion modeling process, which uses standard pellets rather than the more expensive filaments required by other platforms.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing for Defense: Targeting Qualification

Targeting qualification in additive manufacturing for the defense industry means ensuring repeatability as well as reliability as there is much at stake, including human lives. Certain requirements therefore must be met by weapons systems used by the defense industry.

Read MoreA Framework for Qualifying Additively Manufactured Parts

A framework developed by The Barnes Global Advisors illustrates considerations and steps for qualifying additively manufactured parts, using an example familiar to those in AM: the 3D printed bottle opener.

Read MoreAM Materials Consortium Selects Partners for LPBF Fabrication and Testing

The consortium is developing open LPBF parameter sets to streamline machine, material and process qualification, with the goal of expediting customers’ process development leading to serial production.

Read MoreRead Next

The First Choice Was Right: How RP+M Succeeded With Production FDM

This additive manufacturing company narrowed its focus onto the 3D printing capability it knew best and the industry sector best able to benefit from FDM production parts. Characterizing and controlling the process was the breakthrough that has led to production work from Boeing and others.

Read MoreVideo: Orbit X Pro Football Helmet Uses 3D Printed Lattices

The lightweight helmet from Xenith will be used by NFL and collegiate football players beginning in fall 2024.

Read MoreLFAM Phase Two: How Companies Are Going Farther With Large-Part 3D Printing

The freedom to produce very large components more easily is an underappreciated AM advantage, but one that is now established. Recently posted articles show the way forward for large-format additive manufacturing (LFAM) in contract and in-house production, as well as in construction.

Read More.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)