Additive Manufacturing in the Age of COVID-19: Ramping Up for a Fight

Reporting from the front lines of the fight against Coronavirus.

Thought we were out of the woods yet? Think again. After a brief respite, COVID-19 infections are on the rise again, with staggering daily increases coming from more and more states across the U.S. We remain lucky in central Pennsylvania to have not been overrun by the initial surge, although we are seeing a steady rise in cases — think slowly rising tide versus a tidal wave.

Fortunately, we did not let our guard down and planned for the short-, medium-, and long-term implications of Coronavirus and continued volatility to our supply chain as part of our ongoing Manufacturing And Sterilization for COVID-19 (MASC) Initiative at Penn State. Like many, we have been “in it” for over 100 days now, and we recognize that the fight is not over. In fact, it looks like it is ramping up yet again, and we continue to do everything we can with 3D printing, but one can only scale additive manufacturing (AM) so far so fast. Every technology has its limits, and time and cost are two that continue to throttle the adoption of AM.

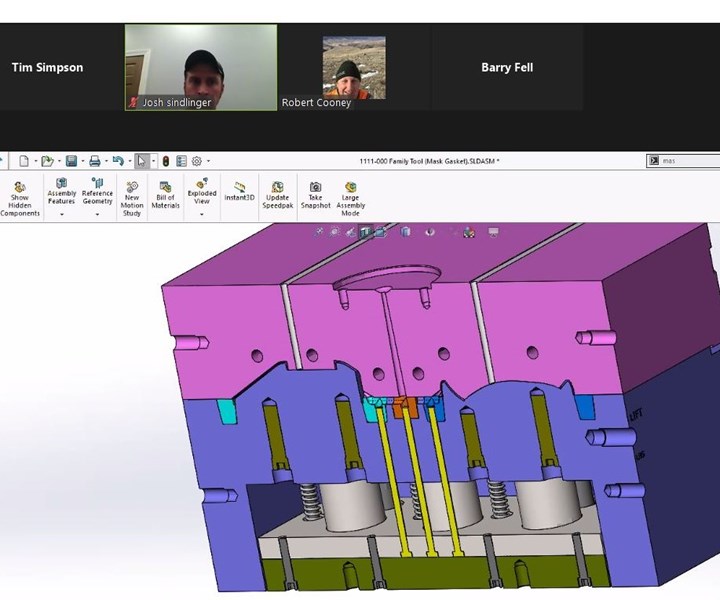

Due to social distancing guidelines, our team had to collaborate remotely to review and finalize tooling design for the injection molded version of our 3D printed filtration mask.

Consider the 3D printed stethoscope that I discussed last month. In response to supply chain disruptions, Penn State’s healthcare workers were facing critical shortages in many personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices like single-patient stethoscopes. Supplies from overseas were still only trickling into the U.S., and domestic medical device manufacturers were still ramping up production and delivering them as quickly as they could, but orders far exceeded the supply. It was literally “hand to mouth” as one manufacturer shared with me.

As our inventory levels dwindled to critical levels, MASC turned to an open source design for a 3D printed stethoscope, which Jessica Menold, an Assistant Professor in Engineering Design at Penn State, and a team of students and colleagues produced within a day. Working closely with the doctors and physicians at Penn State’s Hershey Medical Center, they quickly iterated on the design to improve acoustic quality. After six revisions, the design was finalized, and we began seeking quotes to 3D print and assemble the final components with a manufacturing company registered with the FDA (Remember: I work at a university, not a manufacturer, and we do not manufacture products nor do we have product liability insurance—except for ice cream).

Much to our dismay, the quotes that we received for the 3D printed parts to make the stethoscope were astronomical. Prices ranged from $30-$70 depending on who you talked to and what AM process you used, and that did not include the assembly, sterilization, and packaging that was required for a Class 1 medical device like a manual stethoscope. Granted, prices for single-patient stethoscopes had climbed from $1.25 each to $6.00 each (with a two-month backlog), but even at $30, 3D printing was a non-starter, no matter what volume we quoted. This was an unexpected downside of the economic curve being “flat” for AM, all too often heralded as AM’s main advantage over traditional manufacturing.

We launched another redesign effort with Barry Fell, President of TPC Design and a long-time consultant to Center for Medical Innovation at Hershey, to simplify the design for 3D printing and reduce the number of components without adversely impacting acoustic quality. Through extensive redesign, he was able to get the costs of the 3D printed components down to just over $10, but assembly and packaging costs within a cGMP compliant facility was going to add at least another $2, putting our price point at double the going rate. There is no way to make a business case on that, and we are now forced to weigh the costs and benefits of shifting to more traditional processes like injection molding and vacuum forming to make the components that are now 3D printed. Despite our best attempts, we face the eternal game of chicken-and-egg that every product development team encounters, namely, how much do we invest in tooling and ramp up to bring a product to market versus the expected demand and volatility in the existing supply chain. While I certainly do not know how things will play out next month, let alone the next six months, I will share that our current planning horizon for supply chain disruptions is 18-24 months, and the importance of “supply chain continuity,” a relatively new term to me as an engineer, has never been higher.

On a more positive note, we have successfully turned this corner with the 3D printed filtration masks that I discussed in an earlier writing. Filtration masks, or to be consistent with the FDA, filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs), continue to be highly sought after, especially after the FDA barred nearly 60% of Chinese manufacturers making N95-style masks that did not meet filtration requirements. Luckily, we had long since finalized our design, and this change made it a no-brainer to invest in tooling to injection mold the inner and outer shell for our FFR. We worked closely with Rob Cooney, Manufacturing Manager at Plastikos, and Josh Sindlinger, VP of Evolution Molding Solutions, having been introduced to them by Alicyn Rhoades and Jason Williams, two colleagues at Penn State’s Behrend campus in Erie, PA.

Roughly two weeks and $6,000 later, we had tooling and injection molding capability under our control. Depending on the materials we shot, cycle time varied from 20-25 seconds for the hard plastics we were considering to 90 seconds for the softer plastics being evaluated. Piece-prices varied from about $7.25-$8.50 depending on the quantity being produced. If we amortize the cost of the tooling over its expected life of ~5000 uses, the unit price only rises by a little over $1, keeping the total cost under $10. Granted, this did not include the filtration media, assembly, packaging, etc., but it has certainly put us on a path to ramp up quickly for the fight that is looming.

How did this compare to the cycle time and cost of 3D printing our design? Desktop 3D printing took 6-9 hours for each half of the shell, depending on what system and material you used, and quotes from AM service bureaus were as high as $150 for the two parts to be 3D printed. Newer AM technologies reduced the built time considerably, but prices remained significantly higher than what we could now achieve with injection molding.

As you know, I am a big advocate and promoter for AM, but at the same time, I have to be realistic; otherwise, I would lose all credibility — just when 3D printing is one of the few bright spots within the ongoing pandemic. Knowing when to use AM is just as important as knowing when not to use it, and I hope sharing my story will help you on your AM adventure.

Related Content

3D Printing with Plastic Pellets – What You Need to Know

A few 3D printers today are capable of working directly with resin pellets for feedstock. That brings extreme flexibility in material options, but also requires greater knowledge of how to best process any given resin. Here’s how FGF machine maker JuggerBot 3D addresses both the printing technology and the process know-how.

Read MoreVideo: 5" Diameter Navy Artillery Rounds Made Through Robot Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Instead of Forging

Big Metal Additive conceives additive manufacturing production factory making hundreds of Navy projectile housings per day.

Read MoreMachine Tool Drawbar Made With Additive Manufacturing Saves DMG MORI 90% Lead Time and 67% CO2 Emission

A new production process for the multimetal drawbar replaces an outsourced plating step with directed energy deposition, performing this DED along with roughing, finishing and grinding on a single machine.

Read MoreHow Machining Makes AM Successful for Innovative 3D Manufacturing

Connections between metal 3D printing and CNC machining serve the Indiana manufacturer in many ways. One connection is customer conversations that resemble a machining job shop. Here is a look at a small company that has advanced quickly to become a thriving additive manufacturing part producer.

Read MoreRead Next

Additive Manufacturing Versus COVID-19: The Race for PPE

Reporting from the front lines of the fight against Coronavirus – still deep in the trenches.

Read MoreConsortium Aims to Print COVID-19 Test Swabs at Rate of Millions Per Week

Nasopharyngeal swabs are now available for order and immediate fulfillment through members of this consortium, including: Carbon, Formlabs, Envisiontec and Origin.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing versus COVID-19: Protecting Your Ideas for Protecting Others

Reporting from the front lines of the fight against Coronavirus – battling liability and IP issues.

Read More