Additive Manufacturing Versus COVID-19: The Race for PPE

Reporting from the front lines of the fight against Coronavirus – still deep in the trenches.

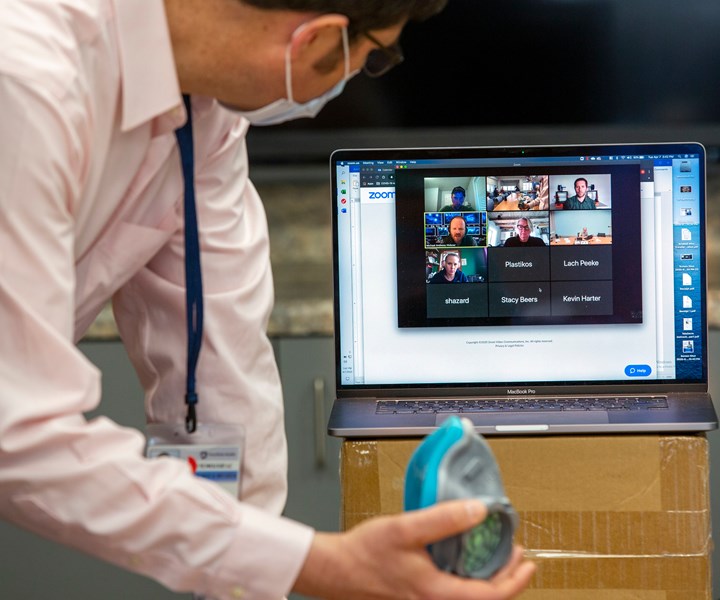

Design reviews and feedback sessions with the faculty, students, doctors, scientists, and industry partners were conducted remotely to practice good social distancing (Image credit: Penn State College of Medicine).

It’s hard to believe that it has been over a month since our lives were turned upside down in the United States by the Coronavirus. As I wrote in my column last month, the move to online classes at Penn State combined with seeing and sharing stories about 3D printed PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) with my network of colleagues, companies and healthcare workers at Penn State’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (PSHMC) landed me right smack in the middle of the fight against COVID-19.

Before I knew it, our informal “grass roots” efforts to help 3D print PPE connected with the University’s senior leadership push to ready the team at PSHMC for the impending “surge” in COVID-19 cases, and I was asked to lead the effort. We named it the Manufacturing And Sterilization for COVID-19 (MASC) Initiative to limit our work to meeting the manufacturing and sterilization needs required to protect healthcare workers and help fight COVID-19. Patient screening, vaccine development, antibody testing, etc. were thus out of scope for us—as they were way outside of my area of expertise.

Like many similar efforts springing up at universities and community makerspaces around the country, our first victory was the 3D printed face shields. We too leveraged the Prusa face shield design that was developed and open sourced by the team in Czechoslovakia. We redesigned it and optimized the processing parameters to reduce the build time by 60%, getting it well under 1 hour. Still, if you want to make 1,000 (or more) face shields a day, you need at least 50 3D printers running all out with minimal build failures and plenty of material on hand. As such, 3D printing provides a good “stop gap” when there is a shortage of manufacturing capacity, but faster production methods were still needed to meet the looming demand.

The 3D printed head band was only one part of the shield, and we reached out in our network to find available laser cutters, and polycarbonate sheet, to make the rest of the face shield design. We found that laser cutters were in short supply in our area, and polycarbonate sheet was soon sold out around the country; thus, we pivoted to the three-hole-punched version like everyone else and used transparency sheets to make the face shield. Unfortunately, as you can image, a face shield with a three-hole-punched transparency sheet will not meet FDA regulations, and it certainly does not pass the ANSI drop-test requirements for protective eyewear (ANSI Z871.1).

Dozens of filtration mask designs and material options were quickly prototyped, evaluated, and revised thanks to 3D printing (Image credit: Matt Briddell, Penn State Center for Medical Innovation).

Luckily, the rapidly expanding network in our MASC Initiative included several companies that were able to pivot their manufacturing lines or set up entirely new lines to produce face shields, in volume, to meet the growing demands at PSHMC and other local hospitals. For instance, the team at Actuated Medical Inc. stood up an entirely new production line in their GMP-compliant facility in under 7 days to make reusable face shields that were compliant with relevant ANSI standards using more traditional manufacturing methods. Meanwhile, Universal Protective Packaging Inc. near PSHMC transformed one of their production lines to start cranking out several 1000 face shields a day using more traditional manufacturing and assembly methods. Both companies are now supplying healthcare workers regionally while also meeting the rising demands from nursing homes, public works crews, police services, and other individuals that are now finding themselves on the front lines of the fight.

While one of our teams was solving the face shield problem, another team was using 3D printing to prototype and test all of the N95-like filtration masks that were being shared online and open sourced. Figure 1 shows some of the filtration mask variations that we tested with doctors and clinicians at PSHMC, and Figure 2 shows one of the feedback sessions conducted over Zoom to adhere to safe lab usage guidelines and practice good social distancing. Based on this feedback, mask designs were quickly modified and revised to improve the fit, comfort, and breathability, and new prototypes were fabricated overnight and tested the next day.

This rapid design iteration and feedback cycle is where 3D printing really excels, and it became even more critical as shortages in supplies emerged—something we did not appreciate at first, but something that drove many of our design decisions. For instance, filtration material could no longer be sourced in the U.S., and alternative supplies of filtration media were quickly exhausted from the shelves of hardware stores. This meant designing a smaller opening in the mask to use less filtration material for the limited supply we had, but this reduced the effective surface area, which reduced the filtering capability of the mask.

A test set-up was developed to evaluate the filtration capabilities of different types and amounts of filtration material, and the mask team determined that adding 3-4 more layers would satisfy the requirements for N95 masks (although we have not been able to certify this given the backlog at NIOSH testing labs right now). Unfortunately, adding that much material made it too hard to breathe through the mask, and so, we went back to the drawing board.

As of this writing, we have solved the filtration problem with some creativity and good old-fashioned engineering, including a bit of advice from a fluid dynamics expert we pulled onto the team, and it looks like we may have found a viable solution that can be mass produced. This was accomplished by engaging an industry partner specializing in tooling and injection molding on the team. They have provided invaluable advice as we modified designs and started to think about scaling up production. As you might guess, 3D printing can make nearly any geometry that is injection molded, but the reverse is not true: complex features that are easily 3D printed will likely lead to exorbitant tooling costs for injection molding—but more on that next month.

Meanwhile, despite its many advantages, keep in mind that no open-source 3D printed PPE has received FDA or NIOSH approval for protecting healthcare workers. Regulatory guidelines have shifted a lot, but make sure that you know and follow the Health Guidelines for 3D Printing Medical Devices and PPE for COVID-19 Response developed by the COVID-19 Healthcare Coalition or other reputable source.

Related Content

SLM Solutions, Assembrix Work to Ensure Secure Remote Printing

Following the integration of Assembrix VMS software into SLM Solutions’ machines, both companies are now working to ensure the enhanced safety and full protection of customers' intellectual property, which is made possible through the utilization of blockchain and encryption technologies.

Read MoreAddUp Receives ASTM Additive Manufacturing Safety Certification

AddUp Inc. announces that it has received the ASTM Additive Manufacturing Safety (AMS) Certification, becoming the first OEM in the AM industry to achieve this significant milestone.

Read MoreChromatic 3D Materials' RX-AM Free of Volatile Isocyanates

RX-AM platform includes software and RX-Flow printers for use in standard and custom configurations.

Read MoreDesktop Metal’s Production System P-1 Features Optional Reactive Safety Kit

The kit features ATEX-rated components, as well as critical hardware and software updates that enable safe printing of ultrafine powders.

Read MoreRead Next

Crushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read MoreProfilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read MorePostprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read More