What Is Vat Photopolymerization?

Vat photopolymerization was the first AM process to be successfully commercialized. Three decades later, this technology has shown how AM is capable of scaling to volume production and making custom products on demand.

Share

Vat photopolymerization’s high resolution makes layering effects almost invisible, as seen in this side-by-side comparison of a Vortic watch case printed on a FormlabsForm2 (clear) and laser powder-bed fusion (metal). The vertical lines still remain, however, due to tesselation effects when converting from CAD to STL file format. Photo Credit: Tim Simpson

Powder-bed fusion (PBF). Directed energy deposition (DED). Binder jetting. How many additive manufacturing (AM) processes are there?

ASTM/ISO standards define seven basic AM processes, which include the three that I have named above as well as vat photopolymerization, material extrusion, material jetting and sheet lamination. While powder bed fusion and directed energy deposition are the most prominent methods for metal AM right now, it is worthwhile to dive into each one of these other processes so that you are aware of their capabilities and potential for use in your company.

The History of Photopolymerization

I’ll begin with vat photopolymerization because it was the first AM process to be successfully commercialized. This process was introduced to the market in the late 1980s by 3D Systems and called stereolithography based on Chuck Hull’s patent for the technology. Even though others had invented aspects of the technology earlier, Chuck Hull is credited by many as “The Father of 3D Printing” because he was the first to bring the technology to market. Thirty years later, he remains very active in the industry, serving as CTO for 3D Systems and deriving new AM technology from his initial patent application (see 3D Systems’ Figure 4 factory solutions).

How Does Vat Photopolymerization Work?

Vat photopolymerization uses a light source to activate a photopolymer, basically a liquid “goo” that hardens when hit by the right wavelength and intensity of light. Early systems had a large vat of liquid photopolymer (hence the name) that was selectively hardened by a laser layer-by-layer to form the part. Material advancements now enable digital light projection (DLP) systems — the exact same ones used to project movies on your wall from your computer — to initiate the cross-linking that hardness the polymers into a solid object.

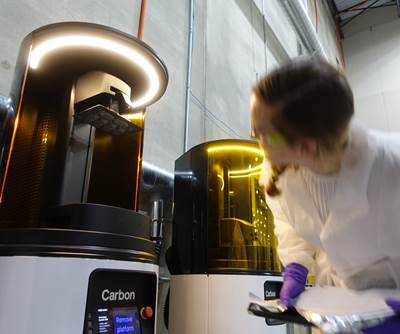

DLP systems are significantly faster than laser-based systems because you can solidify a whole layer at once versus waiting for the laser to trace and fill in the image in each layer. This is why newcomers like Carbon can additively manufacture soles for Adidas so quickly. Their patented Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP) technology enables their systems to look like they are pulling a part out of a puddle just like you might see in a movie. If you haven’t seen their technology in action, check out Carbon’s CEO, Joseph DeSimone’s TED talk where one of their systems additively manufactures a part during his 10:43 minute lecture.

Some vat photopolymerization printers print down onto a build plate, but others like this Carbon CLIP printer print upward from the resin vat. These nozzles for cleaning Vitamix blenders were made with CLIP at The Technology House. The process has also been used for Adidas shoes, medical devices, Ford car parts and much more. Photo Credit: Carbon

Microscale 3D printing is also possible with vat photopolymerization technology. Companies like Boston Micro Fabrication offer printers that can apply this process to very small parts, such as glaucoma stents.

Other opportunities are being realized by blending additives into the resin material. 3D Fortify creates strong mold tools and parts reinforced with fibers using its Fluxprint DLP platform. Ceramics blended into a slurry can be used to create tooling for casting through Admatec’s system. Lithoz and its sister company Incus mix powdered ceramic and metal into the resin, respectively, to create “green” parts that can then be sintered to completion.

These ceramic shells made on an Admatec 3D printer at Aristo Cast were printed in this orientation — the build was stopped prematurely for the sake of this photograph. The shells are used as sacrificial tooling in the metal casting process.

How Is Vat Photopolymerization Used?

Where can you find this 30-year-old AM technology? It has become commonplace in quite a few places now. While Adidas is ramping up production of its FutureCraft 4D shoes via Carbon’s AM platform, Invisalign has been using 3D Systems stereolithography machines to make molds for custom braces for decades. They reportedly make over 320,000 parts a day, showing that AM technology can be scaled to higher volumes when there is a good business case. Not surprisingly, many dentists’ offices are now buying and using vat photopolymerization systems to additively manufacture custom crowns, dentures, implants, etc. directly in their offices using FDA-approved AM materials. Meanwhile, companies like Sonova are using vat photopolymerization systems from EnvisionTec (now part of Desktop Metal’s portfolio) to additively manufacture custom hearing aids, transforming the hearing instrument industry thanks to AM’s ability to produce custom parts on demand with very high resolution.

The lab at Spectrum Dental features several Formlabs 3D printers that are used to make dental models, surgical guides, mouthguards and more, sometimes even as patients wait.

While 3D Systems, Carbon and others are chasing production-scale systems, companies like Formlabs have shifted the discussion to the other end of the spectrum, namely, affordable desktop systems for everyday users. Formlabs launched on KickStarter, a crowd-funding website designed to help bring fledgling projects — and a lot of start-ups — to life, and quickly raised nearly $3 million. They were inundated with orders, which led to numerous delays as they ramped up production, but they ultimately succeed in bringing vat photopolymerization to desktops (you can learn the story of Formlabs and other AM start-ups in the documentary, Print the Legend). Their boxy amber-covered silver systems are becoming ubiquitous, and I find one in nearly every makerspace that I have visited. Meanwhile, they have continued to raise venture funding, develop new materials and launch improved systems. They recently introduced their third-generation system, the Form3 and are offering materials such as “Tough,” which has all sorts of uses for tooling, fixtures and jigs in machine shops and on the factory floor. Recently, they even partnered with Gillette for RazorMaker, allowing users to additively manufacture custom razor blade handles on their systems before being made available on-demand to other consumers.

Vat Photopolymerization 3D Printer Suppliers

What Are the Benefits of Vat Photopolymerization?

As the first additive manufacturing process, vat photopolymerization has come a long way the past three decades. It offers the highest resolution of many AM processes. In many parts, it is nearly impossible to see the layering or staircasing effects that plague other AM processes. Build volumes continue to get bigger, and the latest advancements in software and hardware, combined with new advancements in materials, have opened new avenues for commercialization and profitability. Producing consumer items such as braces, crowns, hearing aids, razor blade handles and soles for your running shoes, vat photopolymerization has shown us that AM is capable of scaling to volume production and making custom products on demand — and sometimes at the same time. How many manufacturing technologies can claim that distinction?

Related Content

3D Systems’ PSLA 270 Creates Midsize, Production-Grade Parts Combining SLA Print Reliability

IMTS 2024: The PSLA 270 is engineered to deliver larger end-use parts more rapidly than similar platforms, bringing tremendous advantages for a breadth of industrial and health care applications.

Read MoreAltana Launches 10 Resin-Based Cubic Ink Materials for 3D printing

The new resins in the Cubic Ink family of 3D printing materials are focused on system-open and industry-applicable additive manufacturing across DLP, LCD and SLA technologies.

Read MoreIs Automation More Effective Than Size for Serial Production 3D Printing?

Micro Factory has developed an mSLA system that incorporates cleaning, curing and part ejection, not to mention 100 empty build plates, into the frame of a desktop machine. The result is a small unit for large-scale production.

Read MoreFizik Utilizes Carbon DLS Technology for One-to-One Program, Creating Customized Bike Saddles

Fizik’s customized bike seat program uses Carbon’s Digital Light Synthesis technology and personalized rider data to create a line of truly custom saddles, giving bike riders the best bike seat for their posterior — only made possible through additive manufacturing.

Read MoreRead Next

Injection Mold or 3D Print? How Resolution Medical Pivots Production

Minnesota manufacturer Resolution Medical is finding opportunities for additive manufacturing via Carbon 3D printers as an alternative to injection molding for production.

Read MoreAM 101: Digital Light Synthesis (DLS)

Digital Light Synthesis (DLS) is the name for Carbon's resin-based 3D printing process. How it works and how it differs from stereolithography.

Read MoreWhat Is Material Jetting 3D Printing?

Recent advances in materials processing capabilities have renewed interest in material jetting, the additive process that allows 3D objects to be built by placing different combinations of material drop-by-drop.

Read More