3D printing is changing the way that manufacturing happens, from start to finish. Just some of the changes are these: Where producing a new part traditionally might have necessitated a capital investment in tooling such as molds, 3D printing requires only a build file and raw material; where conventional manufacturing must deal with waste products such as fluids and chips, 3D printing generates little to no waste; and where parts that might once have been manufactured and held in inventory, the same parts can instead be 3D-printed on demand.

And as a result of changes such as these, the places where manufacturing happens are also changing. 3D printing makes it possible to manufacture virtually anywhere—even, as it turns out, in Brooklyn.

A graffitied building in the borough’s East Williamsburg district is home to Voodoo Mfg., a two-year-old startup producing polymer end-use parts within a 5,000-square-foot space, of which the production floor occupies just 2,000 square feet. Despite a limited footprint, the company is able to compete today with injection molding for batch sizes in the thousands of parts through a combination of 3D printing capacity—specifically, a fleet of more than 200 desktop printers—and manufacturing software developed in-house. With more equipment and planned automation integration, the company hopes to be able to compete with traditional molding for batches of 100,000 parts in the near future.

Hardware-Enabled

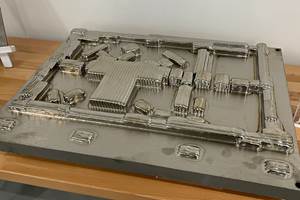

Currently, Voodoo Mfg. says its prices are comparable to injection molding for batch sizes ranging from 1 to 10,000 parts, but with faster turnaround times. This is possible in part just through a sheer quantity of 3D printers. The company’s Brooklyn microfactory is stocked with more than 200 MakerBot Replicator 2 3D printers, stacked two high in custom-built racks to fit within the compact production space. Parts can be printed in PLA or TPU, in a full range of colors.

The company is “aimed at high volumes of commodity parts with no high-end requirements for dimensional accuracy,” says Jonathan Schwartz, co-founder and chief product officer (CPO). Customers range from architecture firms ordering scale models, to industrial clients requiring prototypes or short runs of industrial hardware, to marketing agencies ordering thousands of promotional giveaways, all produced by these printers working in tandem.

Voodoo’s choice of printer is no accident. Its four founders—Schwartz, Max Friefeld, Oliver Ortlieb and Patrick Deem—were all previously employed by MakerBot, and so are intimately familiar with this printer and confident in its ability to produce end-use quality parts. Using the same printer model across the microfactory helps to ensure reliability and prevents any confusion that might come with changing machines from job to job. Owning so many also means there is built-in redundancy; when one goes down, jobs can be rerouted to other printers to allow for repairs or maintenance.

Importantly, though, while the company is engaged in production via 3D printing currently, Voodoo does not consider itself exclusively a 3D printing manufacturer. "We are a digital manufacturing company," says Schwartz, explaining that Voodoo is actually technology agnostic. The company’s philosophy is more about providing a service by hitting the right economics than staying loyal to any particular manufacturing method. For now, that method happens to be 3D printing.

Software-Driven

Though a manufacturing business that relies on desktop 3D printers is unusual in and of itself, perhaps the more significant characteristic of Voodoo Mfg. is the software that makes this “digital manufacturing” model viable. It’s one thing to own a couple hundred 3D printers, but it’s another to be able to receive and deploy jobs to them in an efficient manner. That’s where the software expertise of Voodoo’s founders comes in.

Three of Voodoo’s four founders—Schwartz, Friefeld and Ortlieb—started their first company together, a 3D printing portal called Layer by Layer, in 2012. At the time, there were a number of online services where users could buy and sell designs for 3D printing, but most required customers to purchase the actual 3D model file. This setup meant that many designers were wary of posting designs due to concerns about piracy, and those who did made them very expensive, Schwartz says. So, he and his partners developed a platform using digital rights management (DRM) software that enabled streaming files to customers’ 3D printers in such a way that they never actually held the 3D model, protecting the designers’ work.

Layer by Layer was purchased by MakerBot in February of 2014, and its founders became MakerBot employees. In May of 2015, the three founders plus Patrick Deem, formerly head of mergers and acquisitions at MakerBot, departed to launch Voodoo Mfg. Time spent at MakerBot had convinced the four that it was possible to 3D print quality end-use parts, and so 3D printing became the enabling technology behind a new business that would be based on the ease of online ordering and flexible, on-demand manufacturing.

Such an undertaking in mass customization might not have been feasible without the combination of 3D printing and sophisticated software providing a direct link from design file to production part.

After leaving MakerBot, the founders had to rebuild much of their software from scratch. Not only did they recreate an online ordering system similar to the concept for Layer by Layer, but they also developed the Voodoo Operating System (VOS), a program that Schwartz calls “the brain” of the operation. VOS now drives all parts of the business, from managing incoming orders to controlling the printers themselves. Each of the Replicator 2 printers is tied into this system via a USB connection.

VOS allows Voodoo to manage its full fleet of printers as well as to offer a variety of services for different types of customers. A direct print option, optimized for speed, enables customers to upload a design and have 1 to 100 units manufactured in as little as 24 hours, a good choice for rapid prototyping or one-off manufacturing scenarios. Volume production accommodates batch sizes ranging to 10,000 parts with a turnaround time of two weeks for parts that fit within the 11.2 by 6 by 6.1-inch MakerBot Rep2 envelope. Larger batch sizes and parts can be ordered through the Voodoo sales department, and an in-house design team supports customers needing design assistance.

Voodoo even offers API integration that allows customers to connect their customers directly with Voodoo's microfactory to place orders. As orders come in, VOS dispatches them to the available printers so that manufacturing can begin as quickly as possible. In a recent use case of the API, Voodoo manufactured 10,000 unique designs for Dixie To Go coffee stoppers that consumers created and ordered through Dixie’s website. Such an undertaking in mass customization might not have been feasible without the combination of 3D printing and sophisticated software providing a direct link from design file to production part.

Automation via Project Skywalker

Voodoo’s next goal is to increase its run sizes to 100,000 parts while maintaining prices competitive with injection molding. To get there, the company must cut costs by 90 percent while increasing productivity. It expects to achieve this within the next two years, and automation will be a vital enabler.

Voodoo has recently launched Project Skywalker, a three-phase plan for integrating collaborative robots (cobots) into its operation. The first phase has already begun, with the recent installation of a UR10 robotic arm from Universal Robots in Voodoo’s lab area.

The price point, ease of use and 10-kg payload made this model the best choice for Voodoo's foray into automation, Schwartz says. The UR10, Universal Robots’ largest model, offers six axes of movement and is equipped with force sensors that stop the arm when it encounters resistance—say, if it bumps into a human nearby. The cobot is slower than traditional industrial robots, but this safety feature makes it possible to run the robot without caging, even side by side with humans.

Mounted on a rack with caster wheels, Voodoo Mfg.’s cobot currently tends a group of nine MakerBots stacked in three columns of three. This robot is programmed to take care of the "harvesting" part of the process: once a print is complete, the arm removes the build plate and sets it onto a rack, installs a fresh plate, and presses "start" to begin the print cycle again.

Previously, all these steps would have been done by a human technician, but now the cell can run unattended, opening up the opportunity to run jobs overnight or on weekends without human supervision. Current shifts at Voodoo run 8 hours per day, 5 days per week, hours that could be extended substantially with automation. Parts that come off the printer still must be removed from the build plate and inspected by humans, but entrusting the harvesting step to a cobot will free up technicians to do more of this work.

This nine-printer cell with one cobot is only the first phase. Phase 2 will equip the cobots with vision systems, while the third phase will add motion. That may mean mounting robots onto track systems, or integrating them with automated vehicles for even more flexibility. Eventually, Voodoo envisions a future in which each of its cobots would tend as many as 100 printers. It's also possible that the robots’ role will expand beyond harvesting; cobots could take over refilling the filament of the printers, for instance, Schwartz says.

Outgrowing the Microfactory

Automation alone won't bring costs down by itself, though it will help. The full strategy will entail a combination of cutting expenses and simultaneously growing the business. For example, one potential area for growth could include increased marketing efforts to gain customers, especially those from outside the manufacturing industry such as marketing and events planning companies.

Among the changes to come may also be a shift in technology. 3D printing has been the best choice for production at Voodoo so far, but material costs for filament remain higher than that of injection molding pellets. The company plans to save money by buying larger quantities of filament at a time as production increases, and hopes to see more suppliers getting involved in manufacturing filament, which should help to drive its cost down.

Adding to or changing the production process is another possibility. A portion of Voodoo’s lab space is actually devoted to the testing of other 3D printing technologies at the moment. The business could add or be converted over to another 3D printing method, or integrate processes such as laser cutting or CNC machining. In fact, the company's accounting methods even support this; rather than depreciating its printers over a period of 7 years as is common, Schwartz says, its accounting department uses a timeframe of 24 months. This means any piece of equipment could be phased out after just 2 years if desired.

Physical growth is also a concern. With its 200+ printers, office space, filament storage, part processing area, lab and 21 full-time employees, Voodoo's 5,000-square-foot microfactory is beginning to feel cramped. The business will soon need to relocate, but the plan is to stay in the NYC area, Schwartz says. Many of Voodoo’s customers are in the city, and being close by helps speed delivery. Plus, there’s a wealth of talent for the types of positions the company will need to fill soon (software developer, 3D artist and automation engineer, to name a few). While there is still some room to grow in Voodoo’s current location (the building's high ceilings would allow for more rows of printers, for example), the impending addition of more machines and employees will likely mean a move for the company in the next 6 to 12 months.

Related Content

VulcanForms Is Forging a New Model for Large-Scale Production (and It's More Than 3D Printing)

The MIT spinout leverages proprietary high-power laser powder bed fusion alongside machining in the context of digitized, cost-effective and “maniacally focused” production.

Read More10 Important Developments in Additive Manufacturing Seen at Formnext 2022 (Includes Video)

The leading trade show dedicated to the advance of industrial 3D printing returned to the scale and energy not seen since before the pandemic. More ceramics, fewer supports structures and finding opportunities in wavelengths — these are just some of the AM advances notable at the show this year.

Read MoreDMG MORI: Build Plate “Pucks” Cut Postprocessing Time by 80%

For spinal implants and other small 3D printed parts made through laser powder bed fusion, separate clampable units resting within the build plate provide for easy transfer to a CNC lathe.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreRead Next

The Technology House Steps into 3D Printing for Production

The Technology House was founded on stereolithography for prototyping, but each step forward has been a move toward production. The company is now 3D printing end-use parts, enabled by Carbon’s SpeedCell line and durable materials.

Read MoreVideo: 3D Printing’s Role in the Plastics Industry

This interview from NPE2018 highlights uses of 3D printing technology for the plastics industry, from prototyping through volume production.

Read More3MF File Format for Additive Manufacturing: More Than Geometry

The file format offers a less data-intensive way of recording part geometry, as well as details about build preparation, material, process and more.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)