3D Printing Helps Close the Loop for Armor’s Circular Economy

Manufacturing 3D printing filament was first a way for Armor to recycle its own reclaimed plastic waste. But now, this business unit is helping to close the loop on sustainability for plastic 3D printed products.

Armor first began making 3D printing filament from its own post-industrial scrap. Now, the company is recycling waste from other sources, including products made with its filament.

With the rising buzz around sustainability and green initiatives, selling 3D printing filament made from recycled materials seems like a savvy business choice today. (Indeed, we’ve recently reported on companies both manufacturing and using such filament.) Yet in 2014 when The Armor Group launched its first recycled filament — made from used inkjet printer cartridges — the product was a little ahead of its time.

“There wasn’t much need or demand for recycled materials four or five years ago,” says Pierre-Antoine Pluvinage, global business director of Armor’s 3D printing unit. “There were already lots of suppliers of conventional materials, and the industry was more looking into technical and high-performance materials to serve production of final parts.”

Another person might have been discouraged by this early lack of demand for the product, but Pluvinage was already looking to the future. He and others saw that 3D printing offered not just a new potential business opportunity, but a step forward in Armor’s ongoing pursuit of the circular economy. Today, that initial effort to find a use for internal scrap is rapidly becoming a much larger endeavor, one that could help shape the future of plastics manufacturing.

A Circular Economy from 2D to 3D Printing

In a conventional linear economy, resources are converted into products and sold on to consumers. OEMs source raw materials, design and manufacture their products, and then market and ship them to consumers. Once a product is purchased, though, its value chain effectively ends; the manufacturer no longer has a vested interest in that product or the materials it contains.

A circular economy, by contrast, is one that closes this loop. In this model, the manufacturer assumes responsibility for the product from its creation through the end of its life. When an item is no longer functional or needed, its maker must have a plan for how that used material will be recaptured and then repurposed or recycled into something new.

Pierre-Antoine Pluvinage saw the potential for recycled 3D printing filament early on, before the market truly existed for the product.

Armor has been pursuing a closed-loop circular economy for more than a decade. Headquartered in France, the company is a provider of printer cartridges, thermal tape, industrial inks and other 2D printing supplies. Sustainability efforts, including reclaiming used product, have been a part of its corporate social responsibility platform for years. In 2006, one of these initiatives was collecting used inkjet cartridges for the purpose of remanufacturing them into fresh ones. The idea was a good one, but the system couldn’t handle all the waste generated. Only about 4 out of 10 recovered cartridges were suitable for reuse, which still left behind a significant amount of scrap.

It was Pluvinage (then-strategic project manager) who proposed transforming the 2D printing cartridges into 3D printing filament. As already described, the recycled filament wasn’t an overnight success in 2014. But it was a start, and one that helped the company close the loop on an existing product while exploring a new business opportunity.

Ryan Heitkamp is VP of Armor operations in North America. The company’s Kentucky location will soon be another manufacturing site for Kimya filament.

Shortly after the launch of that first material, the newly established Armor 3D business unit led by Pluvinage also introduced lines of technical and high-performance 3D printing filaments made from virgin stock, under the Kimya brand. (The brand’s name comes from an Arabic word that is the root of “alchemy” — a fitting moniker.)

Those conventional materials provided a foothold for entry into the 3D printing marketplace. Today Kimya encompasses a “three-legged approach” says Ryan Heitkamp, Armor VP of operations in North America. The company continues to offer standard formulations of Kimya-branded filament, while Kimya Lab creates custom formulations and Kimya Factory provides 3D printing services. Filament is produced in France, with production due to expand to the United States in 2020.

3D Printing Is Part of Both the Problem and the Solution

Current Kimya filament offerings include materials made from both virgin and recycled stock. Demand for the latter has grown in recent years, Pluvinage says, with more additive manufacturers not only accepting but now seeking out recycled materials.

He attributes this shift to increasing awareness about sustainability and waste in general, but also to how 3D printing’s rise has democratized manufacturing. When people bring 3D printers into their homes, schools and offices, they become manufacturers — and then have to grapple with the same challenges as manufacturers, including dealing with waste from failed prints or items no longer needed. The same happens in manufacturing facilities that are suddenly able to print items at a moment’s notice, and find themselves accumulating more scrap as a result.

“Even though 3D printing is about making parts using only the material you need, you still make waste like prototypes and items that won’t be needed long-term. Prototyping is still 70 to 80% of the market today,” Pluvinage says. “Companies now see the waste being produced easily, quickly and everywhere. 3D printer users see it with their own eyes, and become more conscious of better reuse of materials and what you do with prints afterward.”

Manufacturers are under growing pressure to operate more sustainably even as this scrap becomes more conspicuous. But this pressure also potentially makes them more open to exploring 3D printing as an alternative production method or as a means of dealing with scrap. Armor 3D has seen an uptick in manufacturers requesting custom materials made from their own post-industrial waste. In such situations, the company can pull together its recycling and materials expertise to create a suitable solution.

As a way of scaling this scrap-to-filament model, the company launched a recycling program in early 2019 to reclaim spools, filament scraps and unneeded prints from its largest filament customers in France. L’Oreal is one example — postproduction plastic waste from the personal care company is converted into filament that it can then use to print future prototypes and tooling.

After collecting plastic waste and receiving the cleaned and pelletized material back from processors, Armor 3D extrudes the filament and packages it for sale. Photo: oioo.fr

Other recycling clients have contributed waste like flexible TPU tubes, PLA food packaging, and even organic materials like leather and oyster shells. These materials could be converted to return to the customer, or be used in a standard Kimya recycled filament. In addition to post-industrial scrap collected from outside manufacturers, the company also uses post-consumer plastic waste like yogurt cups as well as its own scrap and reclaimed product, like those original cartridges. In each case, Armor 3D collects the scrap materials, transfers them to a third-party processor, and then compounds and extrudes the filament itself to return to the customer or release into the marketplace.

Closing the Loop on Plastic Products

Manufacturing 3D printing filament from recycled scrap is a step in the right direction. So, too, is helping other companies reimagine their waste materials as potential feedstock rather than trash. But to truly close the loop on a circular economy, manufacturers will have to deal with post-consumer waste — used product — as well. When I spoke to Pluvinage and Heitkamp in January 2020, Armor 3D was already on a path to tackle this challenge.

“We are about to launch a program in France to start to collect waste from customers, at the end of the lifecycle of our 3D printing materials,” Pluvinage says. Ultimately Armor will collect and recycle not only 3D printing waste from its customers, but also the used 3D printed products that they make and sell. It is possible that future product lines could be made from Kimya recycled filament and recaptured at the end of their lifecycle to be converted back into that filament. This is a twist on the typically proposed circular economy scenario, with the material supplier rather than the product manufacturer taking responsibility for future waste, but it’s a strategy that Armor is well-positioned to execute.

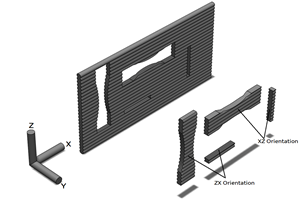

3D printed products like these made with Kimya filament could one day be recaptured and recycled back into filament, closing the loop on the circular economy for the material.

Will other manufacturers follow suit? What will it take to close the loop on a circular economy for plastics? Once again, the challenge that Armor sees is mindset. Manufacturers must get used to recycling their waste and reclaiming used product; likewise, consumers must get used to returning unwanted items.

“We have to make it simple all the way from the consumer to the manufacturer,” Heitkamp says. “That’s where sustainability will unlock itself.”

Pluvinage echoes the sentiment, pointing out that the barriers are primarily not technological, but psychological. “Companies will find a solution, but it’s a matter of deciding,” he says. “We can’t consume like we did before when we saw resources as ‘unlimited.’ We sense and feel now that they are limited, and this is making us move and think differently. Technology is here to help.”

3D Printing and Recycling

This article originally appeared in a recycling collection from sister publication Plastics Technology. Find more on recycling in the plastics industry in this special issue.

Related Content

Multimodal Powders Bring Uniform Layers, Downstream Benefits for Metal Additive Manufacturing

A blend of particle sizes is the key to Uniformity Labs’ powders for 3D printing. The multimodal materials make greater use of the output from gas atomization while bringing productivity advantages to laser powder bed fusion and, increasingly, binder jetting.

Read MoreVideo: A Mechanical Method for Metal Powder Production

Metal Powder Works has developed a method for producing powders from solid barstock, no melting required. This video covers how the process works and benefits of mechanical production of powders.

Read MoreGE Additive Helps Build Large Metal 3D Printed Aerospace Part

The research is part of an initiative to develop more fuel-efficient air transport technologies as well as a strong, globally competitive aeronautical industry supply chain in Europe.

Read MoreEvaluating the Printability and Mechanical Properties of LFAM Regrind

A study conducted by SABIC and Local Motors identified potential for the reuse of scrap reinforced polymer from large-format additive manufacturing. As this method increases in popularity, sustainable practices for recycling excess materials is a burgeoning concern.

Read MoreRead Next

Why “Recycled” Doesn’t Mean Inferior for 3D Printing Filament

GreenGate3D’s PET-G filament is made from recycled plastic, but that doesn’t diminish its quality. How a recycler found a new business opportunity in 3D printing, and how this success might point the way to a more effective recycling ecosystem.

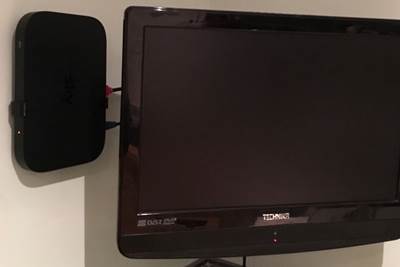

Read MoreHow 3D Printing Enables Sustainability in a High-Turnover Consumer Market

Pengraff UK built its business initially providing mounting solutions for routers and telecommunications equipment, hardware with built-in obsolescence. 3D printing and sustainable materials enable the company to live its values while manufacturing products with a limited lifespan.

Read MoreCarnegie Mellon Helps Industry, Students Prepare for a Manufacturing Future with AM and AI

Work underway at the university’s Next Manufacturing Center and Manufacturing Futures Institute is helping industrial additive manufacturers achieve success today, while applying artificial intelligence, surrogate modeling and more to solve the problems of the future.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)