What Is Directed Energy Deposition?

Analyzing directed energy deposition and powder-bed fusion provides a thorough understanding of the extra machining necessary for a “near-net shape” versus a “net shape” manufacturing process.

In a previous post, I discussed the challenges of making large parts with additive manufacturing (AM), specifically, scaling powder-bed fusion (PBF) processes for large parts because of the inherent cost and build time limitations.

Directed energy deposition (DED) is similar to PBF because it uses a laser (or electron) beam to melt powder. However, the way in which powder feedstock is deposited and melted enables DED to scale more easily and cost-effectively to larger AM parts.

According to the ASTM/ISO standard for AM terminology (ISO/ASTM 52900-15), “DED is an additive manufacturing process in which focused thermal energy is used to fuse materials as they are being deposited.”

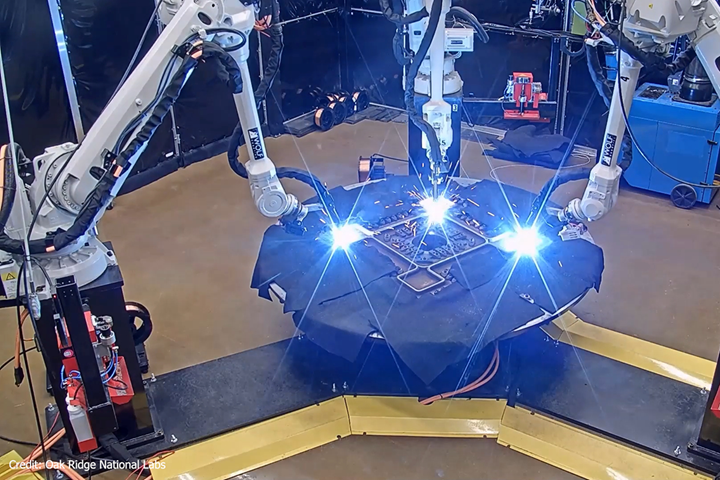

Robot arms are a common motion system for DED 3D printing. This configuratio at Oak Ridge National Laboratory is called Medusa. The three robots coordinate together to apply metal wire to build up the part on the turntable.

What Energy Sources Are Used in DED?

While lasers may be the most popular “focused thermal energy” source for DED, electron beam and plasma arc DED systems are readily available from companies like Sciaky and Norsk Titanium, respectively. For the rest of this piece, however, I am going to focus primarily on laser and powder-feed systems.

Sciaky’s enclosed DED machines use an electron beam to deposit metal wire and build up large parts quickly. Photo Credit: Sciaky

How Does Powder-Fed Laser DED Work?

In laser-based, powder-fed DED, the material being fused is deposited by “blowing” metallic powder through small nozzles or orifices into a melt pool created by the laser. Depending on the power and type of laser being used, the laser beam is focused to create a known spot size (for example, 0.5 or 1 mm for a 500-watt laser versus 1.5 or 3 mm for a 2.5-kilowatt laser). The depth and velocity of the resulting melt pool are dictated by the scan speed of the laser (or movement of the part on the build platform underneath the laser) and the energy absorption and thermal conductivity of the feedstock that is being deposited.

Directed Energy Deposition Equipment: Click here to view suppliers

The size of the melt pool, the speed at which the laser moves and the powder feed rate (the rate at which powder is blown through the nozzles toward the laser) dictate how much powder is captured in the melt pool and ultimately how much material is fused to the part — the layer beneath as well as adjacent material within the layer currently being built. A large, hot, slow-moving melt pool will have a higher powder capture rate (70- to 80-percent, which is the best case) than a smaller or faster moving melt pool (20- to 30-percent capture rate, which is the worst case). However, the thermal history and therefore the microstructure and mechanical properties of the AM part will be different in the two cases. This is one of the challenges with DED, namely, tuning your process parameters to ensure a fast build time, efficient use of powder and a part that is dimensionally accurate.

How Does DED Compare to Powder Bed Fusion?

Once optimized, build rates for DED tend to be a little faster than PBF. The laser spot size for DED is at least 10X or larger compared to what is used in PBF. This creates a larger melt pool target for the powder to hit, melt and fuse together. Can you imagine what powder-capture rates would be if you were trying to hit a 50- to 75-micron diameter melt pool in a PBF system?

Also, larger powder particles tend to be used in DED systems (50- to 150-microns in diameter in DED versus 20- to 50-microns for PBF), as they tend to flow better and provide more surface area to speed the melting process. Larger powder particles also enable thicker layers compared to PBF, which means fewer layers to build when using DED.

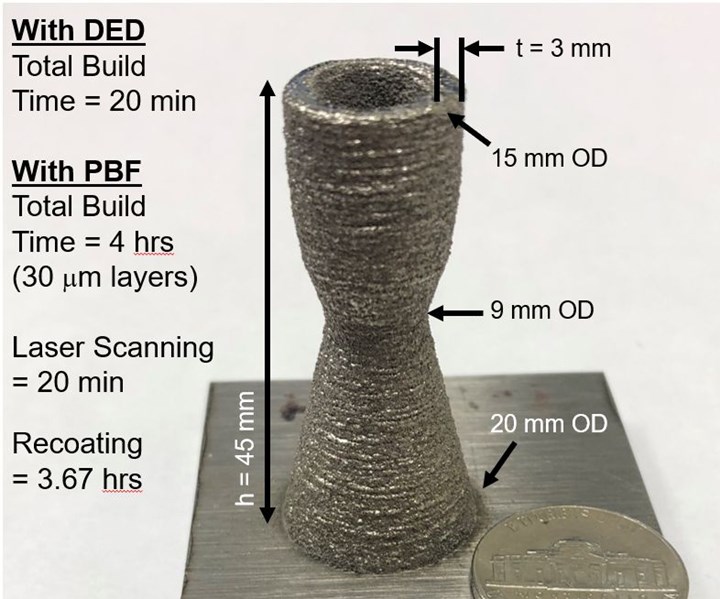

Consider the nozzle shown in the figure. This nozzle only takes about 20 minutes to build on our 500-watt laser-based, powder feed DED system in Ti-6Al-4V. Building the same part on our 400-watt laser-based PBF system also takes about 20 minutes of laser scan time, but the total build time for the part on a PBF system is nearly four hours when you factor in recoating.

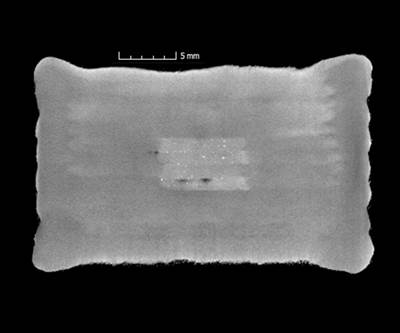

Build-time comparisons for laser-based DED and PBF for a small titanium nozzle. The material is Ti-6Al-4V. Photo Credit: Penn State CIMP-3D 2019

Why the large difference? With DED, you only deposit material where you need it. The laser simply moves three to four times around the circumference of the nozzle to build a layer and the next layer starts immediately after the laser is repositioned. With PBF, however, the next layer can only begin after a new layer of powder has been spread. So, if the part is built using 30-micron layers, then the 45-mm-tall nozzle has 1,500 layers. Multiply the number of layers by the time it takes to recoat a single layer (about 9 seconds for Ti-6Al-4V), and the recoating time is 3.67 hours. Granted, current laser PBF systems build Ti-6Al-4V parts using 60-micron layers (or 90 microns in some systems), but that still means the build time for the nozzle on a PBF system is nearly two hours (or 1.5 hours at 90-micron layers).

While the DED nozzle builds faster, you can see in the figure that the surface finish on the part is pretty rough (comparable to what is achieved when sand casting). You can see many of the actual layers, and the dimensional accuracy of the part is much less than what is possible on a PBF system. As a result, more machining will be likely needed to finish a DED part and meet specifications. Because of this, many consider DED more of a “near net shape” process versus a “net shape” manufacturing process like PBF, but as I said last month, that is good news for you machining professionals out there as AM with DED means more business for you.

Related Content

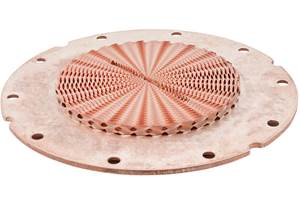

With Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM), Cooling Technology Is Advancing by Degrees

San Diego-based Fabric8Labs is applying electroplating chemistries and DLP-style machines to 3D print cold plates for the semiconductor industry in pure copper. These complex geometries combined with the rise of liquid cooling systems promise significant improvements for thermal management.

Read MoreThis Year I Have Seen a Lot of AM for the Military — What Is Going On?

Audience members have similar questions. What is the Department of Defense’s interest in making hardware via 3D printing over conventional methods? Here are three manufacturing concerns that are particular to the military.

Read MoreVideo: 5" Diameter Navy Artillery Rounds Made Through Robot Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Instead of Forging

Big Metal Additive conceives additive manufacturing production factory making hundreds of Navy projectile housings per day.

Read MoreDMG MORI: Build Plate “Pucks” Cut Postprocessing Time by 80%

For spinal implants and other small 3D printed parts made through laser powder bed fusion, separate clampable units resting within the build plate provide for easy transfer to a CNC lathe.

Read MoreRead Next

Three Cool Uses for Directed Energy Deposition

Most machining professionals don’t like to admit that they ever make mistakes, but every now and then wouldn’t it be nice to have an “eraser” to go back and repair a gouge or fix a nicked edge? Or maybe you took off a bit too much material on that last machining pass and you’d like to add it back? Well, directed energy deposition (DED) enables you to do that and more.

Read MorePostprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read MoreCrushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read More