Is There a Larger Role for Additives in Additive Manufacturing?

Terminology confusion might be coming, because the answer is likely yes. A provider of glass flake for plastics foresees applications to AM, specifically as a reinforcement within 3D printing filament.

Are additives a solution whose full promise is yet to be realized for additive manufacturing (AM)? Almost certainly yes, says Ed Malison, business development manager with NSG, provider of glass flake additives. In plastics manufacturing, solid additives — elements within the melted polymer such as beads, fibers and flake — have long been used to provide bulk in some cases, and more relevant to 3D printing, reinforcement and stability. As AM expands into more and more plastics production, finding ways to incorporate additives into raw stock such as 3D printing filament will become increasingly valuable.

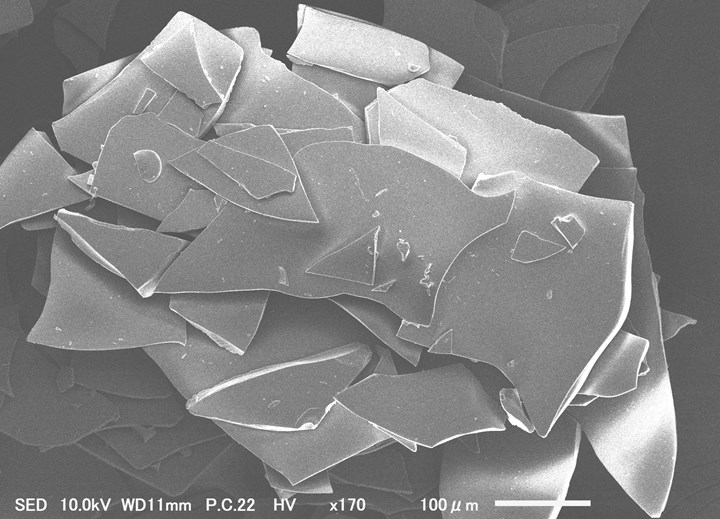

Malison says he is looking for the chance to work with filament makers on applying glass flake to 3D printing. This additive is ready for AM, he says. The most common glass flake used in plastics manufacturing such as injection molding is about 160 microns in diameter by 5 microns thick, which is potentially too large for use through the nozzles of fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D printers. But more recently developed technology allows his company to produce glass flake an order of magnitude smaller — down to 8 microns in diameter by 0.5 micron thick.

Glass flake even smaller than the flakes seen here can flow easily through the nozzles of FFF printers, providing reinforcement for polymer AM parts. Photo Credit: NSG

Glass flake is perhaps the most promising plastics-industry solid additive for application to 3D printing. Acting as a multidirectional anchor within the material, glass flake tends to compensate for both the anisotropic strength and the distortion tendency of parts made through FFF. Chopped fiber, a solid reinforcing additive currently used in 3D printing, does not accomplish this as effectively, he says, because the fibers tend to orient in parallel as they follow the flow of material deposition. Glass flakes throughout the material orient randomly, essentially holding the material in place along every direction at once.

It will take testing to see just how much value this can bring to 3D printing filament, he says. But the widespread application to plastics in general suggests glass flake will be a natural area of development for material for additive.

Indeed, the way we communicate about 3D printing and its materials might therefore need to change, he notes. Today, “additive” is often used as a shorthand for additive manufacturing (as I used it at the end of the preceding paragraph). This shorthand might become confusing in the future, when additives become a commonplace element of AM applications.

Related Content

-

Savage Automation Delivers 3D Printed Commercial Manufacturing Aids

The company's approach to designing end-of-arm tooling and other devices has evolved over the years to support longevity and repairs.

-

Evaluating the Printability and Mechanical Properties of LFAM Regrind

A study conducted by SABIC and Local Motors identified potential for the reuse of scrap reinforced polymer from large-format additive manufacturing. As this method increases in popularity, sustainable practices for recycling excess materials is a burgeoning concern.

-

3D Printed Preforms Improve Strength of Composite Brackets: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

On this episode, we look at a pin bracket for the overhead bin of an airplane made in two composite versions: one with continuous fiber 3D printed reinforcements plus chopped fiber material, and one molded from chopped fiber alone.