How a Solid-State Process Stood Firm Until Additive’s Moment

Early on, this company saw the promise of friction stir welding for building forms in layers. Few understood at the time. They understand now, in part because this process offers benefits such as blended materials and freedom from stress that other metal AM approaches can’t match.

FRICTION STIR WELDING ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING

Nanci Hardwick of Meld Manufacturing bought out both the partners she founded the business with, first one and then the other, during a trying period of just two months. Buying out one strained her finances. Buying out the other left her nearly broke. Both had separate reasons for leaving. She had her continued confidence in the promise of the business keeping her in. Her choice was vindicated years later, when the world caught up with her in part because it found a name for what she was doing—additive manufacturing.

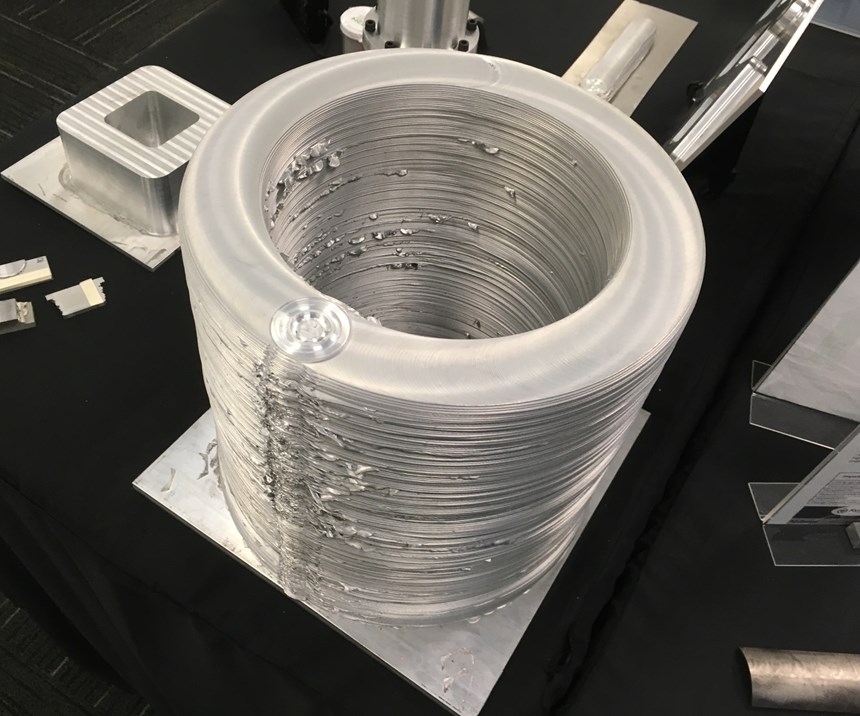

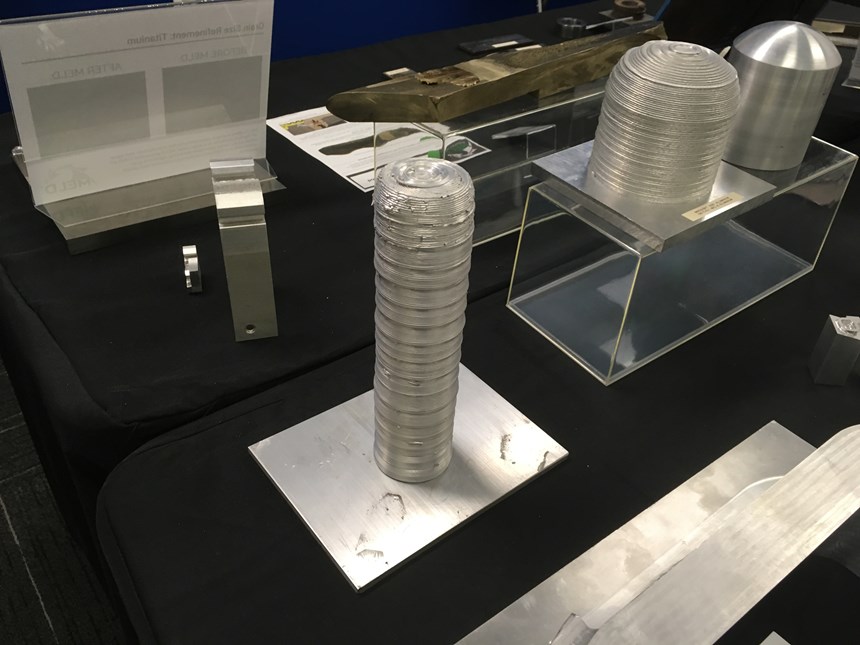

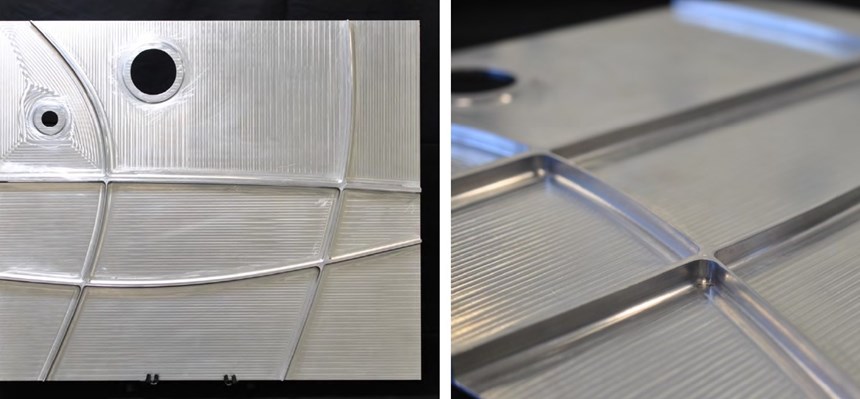

Meld was founded on the idea of doing friction stir welding better, she says, enabling more of the promise that friction stir welding can achieve. Part of that promise: Friction stir welding can be a means of depositing metal along a precisely controlled path in order to build 3D forms in layers. To early observers, this was seen as a weird or even ludicrous use of the process. Why stack up layers of metal? The idea of 3D printing as a concept within metal parts manufacturing had not yet taken hold. Meld therefore has a metal additive manufacturing (AM) process that is hardly new, yet it remains distinct like a newcomer today because of benefits it brings that other metal additive processes cannot match.

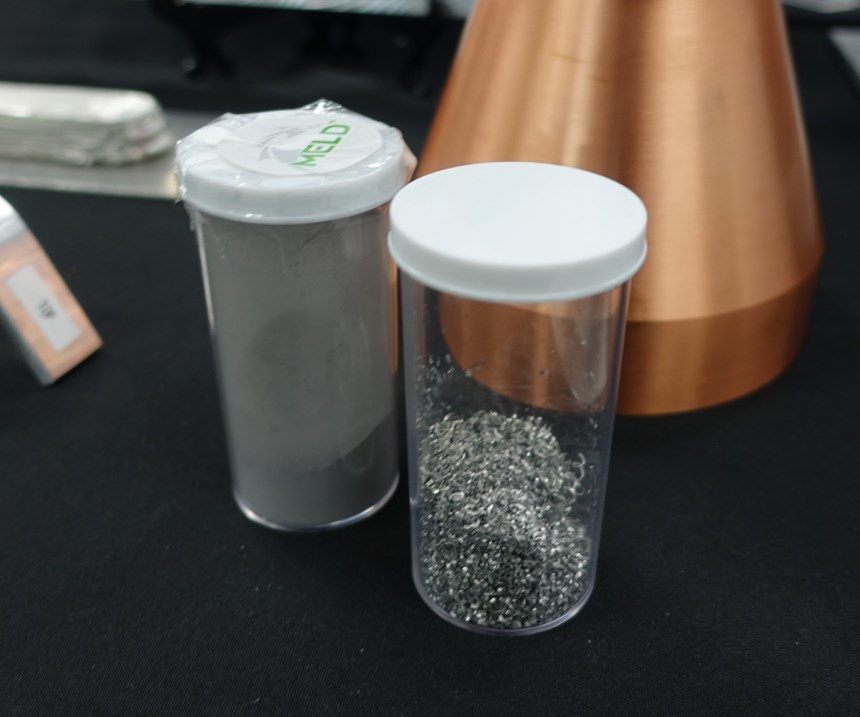

For example, since the mechanism is friction stir welding—plasticization using friction and pressure rather than melting—the original state of the material is, well, immaterial. Meld's process can print with powder, but it doesn’t need powder. It prints just as well using a solid bar as the starting material. It can even 3D print using the chips that are left over after machining.

Moreover, the build cycle using this mechanism can apply different metals in alternation. On the day I visited the company at its headquarters in Christiansburg, Virginia, a Meld machine was making a part for a customer by alternating thin layers of two different metals in order take advantage of the properties of both. The machine switched between applying friction stir welding first with one bar, then with another. The result was a part that would be hard to build using melted metal and impossible to achieve in a machine with a powder bed.

“Blending dissimilar metals is the real promise of this capability,” Hardwick says.

Turn and Press

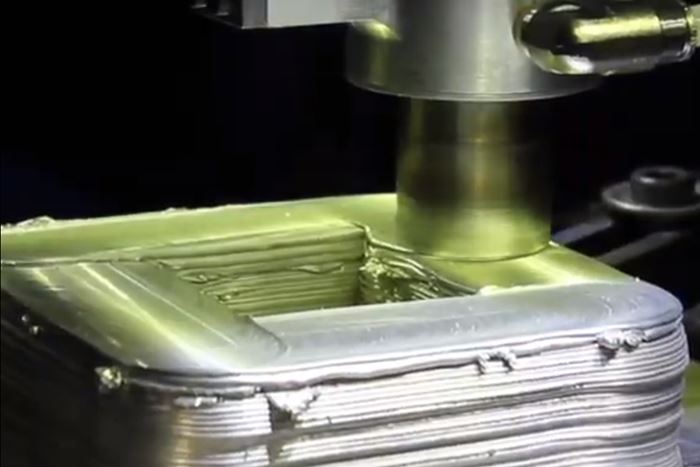

Friction stir welding is solid-state metal deposition that works by surpassing the metal’s yield strength. Metal stock is fed and rotated while pressed against a surface at high force. No liquification of the metal means no resolidification, meaning no introduction of kinds of residual stress that create distortion problems in other 3D printing processes. No melting also means this welding works well for non-fusion-friendly metals such as magnesium, copper and steel. Take a look at how this process works, below:

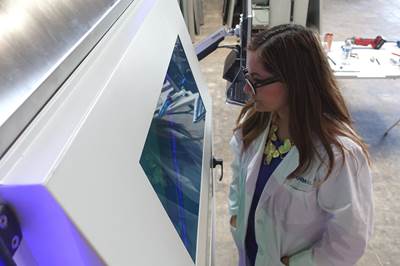

Meld’s process is friction stir welding with a third dimension, Hardwick says. It’s more than that, too—the company has patented various friction stir welding improvements. Hardwick came from the software industry to join her two cofounders in launching the company in 2007, intrigued by manufacturing and the prospect of “making something tangible and real,” she says. But the role Meld ought to play for its users was not clear to the founders at first and would not become clear for years. The technology can be used for building parts, building features, coating, joining, repair—but which applications were most worth focusing on? And at a more basic level, should the company supply parts or machines?

“We were a solution looking for problem,” she says. That changed when she discovered one particular category of solutions: AM. Or more accurately, the category discovered her. The struggle for acceptance she had faced since the beginning seemed suddenly to end one day, because suddenly there was a basis for understanding what she offered. The concept of additive manufacturing had taken hold and become widespread throughout industry, and suddenly both Meld's process and its promise were appreciated.

“The reaction was no longer, ‘What do you mean you deposit metal in layers?’” she says. “The reaction became, ‘Wow, you deposit metal in layers … and without residual stress!’”

The question of parts versus machines was solved soon after this. One of the most valuable applications the company encountered proved to be repair of large components that are costly to scrap. She heard a manufacturer in the defense industry describe the critical machining that had to be performed on a $600,000 part, and the risk of scrapping this part if the machining was in error. “As soon as I heard that figure, I thought, ‘Why are we standing here talking? Let’s build him a machine!’” A large machine for repair via the Meld process offered an effective way to undo those machining errors and save those expensive parts. Meld Manufacturing has been a maker of machine tools ever since.

And in this case, “machine tool” is the right word. The process requires spindle rotation and three-axis motion—the same requirements of a CNC machining center. The Meld machine therefore looks and acts like a machining center, including using a control interface any machine shop would find familiar.

The Problems Come

Far from offering a solution in search of a problem, Hardwick says she and her team now have the “pure joy” of problems coming in. “During the last two years, we haven’t had to explain,” she says. “Nearly all our conversations begin with an understanding of what our machine aims to do.” This is a big change. The idea of additive manufacturing has been sold; the questions now come down to the benefits and implementation of her approach.

“People actually come to us now who have been told by their bosses that they need to be in AM,” she says. Few new technologies get to enjoy a glow like this. She worked for a long time without this glow. A new or different technology typically faces an inherent resistance to change as its all-but-insurmountable obstacle. That’s what Hardwick used to face and for a time faced alone. Then something happened. She saw the coming of additive’s moment—this moment we continue to experience in which the opportunities for creating by layering material are still building.

Related Content

Postprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read MoreBeehive Industries Is Going Big on Small-Scale Engines Made Through Additive Manufacturing

Backed by decades of experience in both aviation and additive, the company is now laser-focused on a single goal: developing, proving and scaling production of engines providing 5,000 lbs of thrust or less.

Read MoreThis Year I Have Seen a Lot of AM for the Military — What Is Going On?

Audience members have similar questions. What is the Department of Defense’s interest in making hardware via 3D printing over conventional methods? Here are three manufacturing concerns that are particular to the military.

Read MorePossibilities From Electroplating 3D Printed Plastic Parts

Adding layers of nickel or copper to 3D printed polymer can impart desired properties such as electrical conductivity, EMI shielding, abrasion resistance and improved strength — approaching and even exceeding 3D printed metal, according to RePliForm.

Read MoreRead Next

Directing the Future of Laser Metal Deposition (LMD)

Formalloy is proving that LMD is for more than repairs and large parts. Fast deposition rates, fine detail capabilities and multimaterial support promise to change how parts are designed and made.

Read MoreVideo: How Additive Manufacturing Is Advancing the Space Industry

By making launch vehicles more efficient and easier to manufacture, AM lets small companies play a significant role in space. Here is a conversation with an aspiring startup.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More