Divergent Technologies Eyes High-Volume, Optimized Automotive Production Through Additive

While some automotive OEMs are using additive here and there, Divergent Technologies is basing its vehicles on 3D printed structures.

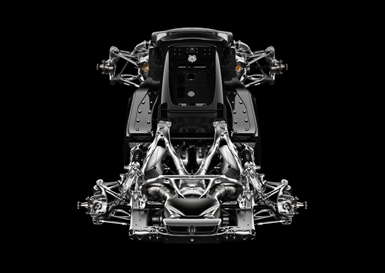

For the chassis of the Czinger 21C there are some 350 parts printed, most with aluminum alloys. The parts are assembled in a fully automated cell. Adhesive bonding is primarily used.

Photo Credit: Divergent Technologies

One of the most notable vehicles at the 2016 Los Angeles Auto Show didn’t come from a major OEM.

Rather, the Blade, an exotic hypercar, was staged by a Torrance, California-based company named Divergent Technologies.

The reason the car garnered so much attention — in addition to the exceptional execution of the body — was because it was promoted as being “3D printed.”

At that time, the whole notion of a 3D printed car was as exotic as the vehicle itself.

Kevin Czinger, founder, lead inventor and CEO of Divergent had a hit on his hands.

Mike Kenworthy, chief technology officer at Divergent, says that what was meant to be a technology demonstrator had such positive feedback that the decision was made to fully develop the car, which is now known as the 21C and produced by Czinger Vehicles, a separate company that was created in 2019 and shares space with Divergent.

After the 21C, Czinger didn’t have just the creation of a car in mind. He worked to develop a different way to design, engineer and manufacture vehicles.

A Whole Systems Approach

The 21C is a hybrid — the total output is 1,250 hp. The additive-intensive car has a curb weight of approximately 2,910 pounds. It has a base price of approximately $2 million.

Photo Credit: Divergent Technologies

The Divergent Adaptive Production System (DAPS) was created, a system that includes artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced materials and, arguably at the heart of it, additive manufacturing.

One of the fundamentals of DAPS, Kenworthy says, is that there is no design-specific tooling. If something needs to be changed, then it is a matter of programming, not cutting metal for new tools, whether these are tools to create or process the components.

This is why additive is essential to the process.

“We’re doing around 350 parts per vehicle,” Kenworthy says, “primarily aluminum printed components.” There are some nickel- and titanium-alloy parts and a “handful” of fiber-reinforced plastic parts.

While traditional OEMs are using additive mainly to produce trim pieces or assembly aids, Divergent is printing the 21C’s chassis, as well as structural components such as rear frames and engine cradles for the company’s other automotive customers.

Creating the Code for Optimization

Kenworthy says that Divergent personnel spent a number of years developing the ways and means to create components to the extent that they created the company’s own topology optimization software called Bi-directional Evolutionary Structural Optimization.

Kenworthy says that because a given structure, such as a rear frame for a vehicle, is too large to be printed in a single piece, it is designed so that it will be constructed of X-number of pieces. The design software takes into account not only how to partition the overall component but the requirements of the automated assembly cell that will put those parts together, as well as the assembly sequence.

“We’re looking at the overall Pareto optimization — the Pareto frontier of that massive set of system constraints and then picking the best overall solution. This is where the humans come into the AI design —picking the design that will be used.”

Faster Processing

Then there is the additive process. The primary type of equipment that Divergent is using is an SLM Solutions NXG ZII 600, a machine that deploys 12 1,000-W lasers and provides a work envelope of 600 x 600 x 600 mm. Divergent has five systems and Kenworthy says the company has been working with SLM for about five years.

“We’ve been operating it for about two years now,” he says, and that compared to firms using other state-of-the-art, four-laser systems, “We’re generally printing, depending on the circumstance, 10 to 20 times faster than service bureaus operating with that other equipment.”

He says that Divergent is printing, on average, “around a kilogram or a kilogram-and-a-half per hour.”

Materials and Adhesives

Which goes to the materials. “When it comes to aluminum, this is where we focus our development. We invented and developed a number of proprietary aluminum alloys optimized for our system and for different applications across a car.”

For example, Divergent developed an alloy for crash-energy management structures and another for high-temperature applications. It uses suppliers to create the powders to its specifications.

The parts are printed and move to the robot-based automated assembly cell. Kenworthy says that Divergent primarily uses adhesive bonding to put components together.

And the company developed its own adhesives. He says that in the assembly, components are put together initially with a UV-cured adhesive. “Think of these as tack welds,” he says.

The company personnel performed hundreds of adhesive tests, he says, and the best one they were able to find could UV cure in about 40 seconds.

The adhesive Divergent developed cures in about three seconds. What’s more, Kenworthy says, the primary structural adhesive used to fully bond the parts is heat cured and the UV curing adhesive is capable of doing its job during the heat curing.

While it may sound like Divergent has developed quite a few things, this is only scratching the surface. Kenworthy says it has extensive intellectual property, including over 500 patents, ranging from the software used to the materials to the part designs. “We spent a number of years engineering the joint architecture and the overall system to enable that.”

Growing the Volumes

Although the 21C is going to be limited to 80 units, Kenworthy notes that Czinger is going to be coming out with higher-volume models like the four-passenger Hyper GT.

Kenworthy says that DAPS is configured to be able to accommodate high volumes—and he’s talking in the thousands, not hundreds.

Not only are there the vehicles being built for the Czinger brand, but work being done for other OEMs: “Were focused initially on the luxury brands within larger automotive groups” — and he says these are companies anyone would recognize— “demonstrating the technology, then moving down into other segments.”

He emphasizes that Divergent is not a service bureau: “We’re a Tier One manufacturer. We do the full scope of design, engineering and validation. We become embedded in the overall vehicle timeline and processes.”

And he is a believer in the benefit of additive to automotive manufacturing on a larger scale. He points out the frame structures and suspension components the company is currently producing account for as much as 100 kg of printed mass on a car.

“The companies that deploy these types of solutions are going to be more successful and outcompete those that aren’t,” he says.

Related Content

BMW Group Vehicle to Adopt 3D Printed Center Console

A vehicle coming to market in 2027 will include a center console carrier manufactured through polymer robot-based large-format additive manufacturing (LFAM).

Read More8 Transformations 3D Printing Is Making Possible

Additive manufacturing changes every space it touches; progress can be tracked by looking for moments of transformation. Here are 8 places where 3D printing is enabling transformative change.

Read MoreA Tour of The Stratasys Direct Manufacturing Facility

The company's Belton manufacturing site in Texas is growing to support its various 3D printing applications for mass production in industries such as automotive and aerospace.

Read More8 Cool Parts From Formnext 2024: The Cool Parts Show #78

End-use parts found at Formnext this year address various aspects of additive's advance, notably AM winning on cost against established processes.

Read MoreRead Next

Video: Topology Optimization versus Generative Design

Why do these strategies matter in design for additive manufacturing (DFAM), and what’s the difference? A conversation with PADT’s Eric Miller explores AM and design, including its human element.

Read More3D Printed Tool for Machining Electric Vehicle Motors: The Cool Parts Show #39

Additive manufacturing achieves a large-diameter cutting tool light enough for fast, precise machining of the motor housing’s stator bore.

Read MoreProfilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)