Arcam CEO Speaks of Promise and Progress in Aerospace and Orthopedic Industries

Growth is expected as both industries transition more production components to AM.

At Arcam’s Investor Day last week, the company welcomed investors in the NASDAQ-listed firm to the company’s new U.S. headquarters in Woburn, Massachusetts (near Boston). President and CEO Magnus René, who spoke at length at the event, recently relocated from the company’s home in Sweden to be based at this new office. The reason for his move, he told the group, is because the United States is the company’s “biggest market and biggest opportunity.”

The move also brings him nearer to Arcam’s two acquired business units, both based in North America. AP&C in Quebec supplies powder metal for additive manufacturing. DiSanto Technology in Connecticut provides contract manufacturing services including both additive manufacturing (on Arcam machines) and CNC machining. Meanwhile, parent company Arcam makes AM systems building 3D metal parts through electron beam melting, or EBM. René says Arcam is therefore the only company to combine all of these different facets of metal AM under a single corporate ownership.

The chief market sectors for the company are orthopedic implants and aerospace components. These two product types have important traits that make them ideal for additive, he told investors. Both are characterized by high material costs and low production volumes, and both stand to benefit significantly from the expanded design freedom that AM provides. His message to the audience was that there is dramatic potential for the growth of AM in both of these sectors. Indeed, he says, the adoption of AM is at only the very earliest stages in both industries.

In orthopedics, Arcam’s point of entry has been improved part performance through design freedom. Specifically, implant surface geometries formed through AM provide for superior fusing with the patient’s bone compared to traditional implant surfaces created through spray technology. Additive implants have been adopted and are in use today for this reason. Building on this success, René expects AM to be adopted next for the production of “outlier” implant part numbers made in such low volumes as to be awkward to produce through conventional manufacturing. From there, he expects the implant makers to bring this same approach to manufacturing more standard parts, applying AM in many cases to eliminate the need for forging and dramatically reduce the need for machining.

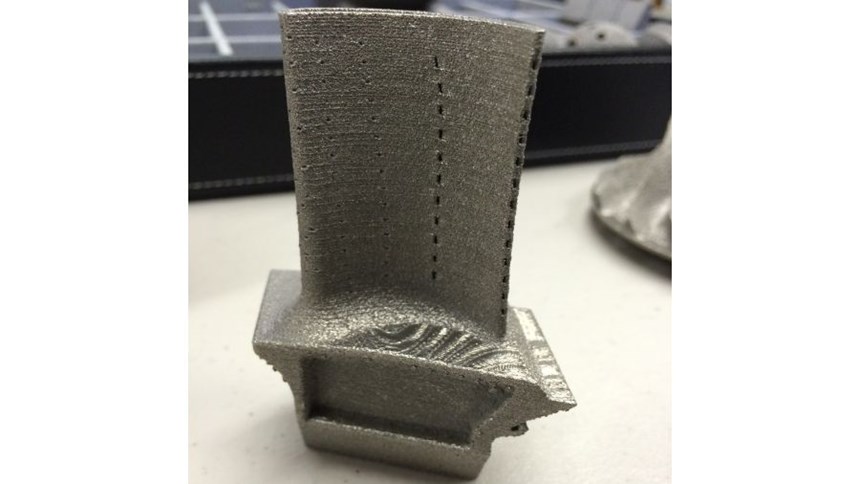

By contrast, in aerospace, he says the point of entry has been essentially at the opposite end of this progression. The initial uses of AM for aerospace parts have served primarily to replace standard processes in the production of parts that are particularly difficult to make. Examples of this are still coming—a titanium aluminide aircraft turbine blade made from EBM as a replacement for casting will go into production in 2018. Later, he says, aerospace companies will build on successes such as this with existing part designs by leveraging AM’s design freedoms to realize new parts that offer improved performance.

But even the volume of existing parts presents important challenges. Just the aforementioned blade—a single part number for a single aircraft engine maker—will require 30 to 40 EBM machines to satisfy the eventual production demand. René says this illustrates why the next step for Arcam will have to be a further “industrialization” of both the company and its technology. That is, the company will have to prepare to meet the demand as additive-manufactured parts increasingly move beyond development and into full production.

Related Content

ActivArmor Casts and Splints Are Shifting to Point-of-Care 3D Printing

ActivArmor offers individualized, 3D printed casts and splints for various diagnoses. The company is in the process of shifting to point-of-care printing and aims to promote positive healing outcomes and improved hygienics with customized support devices.

Read MoreFDA-Approved Spine Implant Made with PEEK: The Cool Parts Show #63

Curiteva now manufactures these cervical spine implants using an unusual 3D printing method: fused strand deposition. Learn how the process works and why it’s a good pairing with PEEK in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreUnderstanding PEKK and PEEK for 3D Printing: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

Both materials offer properties desirable for medical implants, among other applications. In this bonus episode, hear more from Oxford Performance Materials and Curiteva about how these companies are applying PEKK and PEEK, respectively.

Read MoreOvercoming Challenges with 3D Printing Nitinol (and Other Oxygen-Sensitive Alloys) Through Atmospheric Control

3D printed nitinol has potential applications in dental, medical and more but oxygen pickup can make this material challenging to process. Linde shares how atmospheric monitoring and the use of special gas mixtures can help maintain the correct atmosphere for printing this shape alloy and other metals.

Read MoreRead Next

Crushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read MoreProfilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read More