Rutgers Engineers Create Faster, More Precise 3D Printing Process

Researchers says their Multiplexed Fused Filament Fabrication Process could be a game changer for the 3D printing industry.

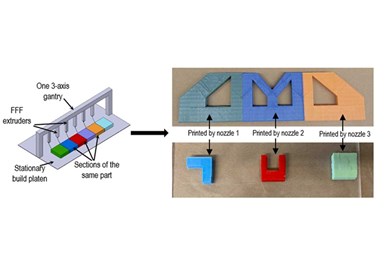

By programming a prototype to move in efficient patterns and by using a series of small nozzles to deposit molten material, researchers say they were able to increase printing resolution and size as well as significantly decrease printing time. Photo Credit: Rutgers School of Engineering

Rutgers engineers says they have created a way to 3D print large, complex parts at a fraction of the cost of current methods.

“We have more tests to run to understand the strength and geometric potential of the parts we can make, but as long as those elements are there, we believe this could be a game changer for the industry,” says Jeremy Cleeman, a graduate student researcher at the Rutgers School of Engineering and the lead author of the study.

The approach is called Multiplexed Fused Filament Fabrication (MF3), which uses a single gantry (the sliding structure on a 3D printer) to print individual or multiple parts simultaneously. By programming a prototype to move in efficient patterns and by using a series of small nozzles — rather than a single large nozzle, as is common in conventional printing — to deposit molten material, the researchers say they were able to increase printing resolution and size as well as significantly decrease printing time.

“MF3 will change how thermoplastic printing is done,” Cleeman says.

According to the researchers, the 3D-printing industry has struggled with what is known as the throughput resolution tradeoff — the speed at which 3D printers deposit material versus the resolution of the finished product. It is said larger diameter nozzles are faster than smaller ones but may generate more ridges and contours that must be smoothed out later, adding significant postproduction costs.

By contrast, smaller nozzles deposit material with greater resolution, but researchers say current methods with conventional software are too slow to be cost effective.

At the heart of MF3’s innovation is its software. To program a 3D printer, engineers use a software tool called a slicer — computer code that maps an object into the virtual “slices” or layers that will be printed. Rutgers researchers wrote slicer software they say optimized the gantry arm’s movement and determined when the nozzles should be turned on and off to achieve the highest efficiency. MF3’s toolpath strategy makes it possible to “concurrently print multiple, geometrically distinct, noncontiguous parts of varying sizes” using a single printer, the researchers wrote in their study.

Cleeman said he sees numerous benefits to this technology. For one, the hardware used in MF3 can be purchased off the shelf and doesn’t need to be customized, making potential adoption easier.

Additionally, because the nozzles can be turned on and off independently, an MF3 printer has built-in resiliency, making it less prone to costly downtime, Cleeman adds. For instance, when a nozzle fails in a conventional printer, the printing process must be halted. In MF3 printing, the work of a malfunctioning nozzle can be assumed by another nozzle on the same arm.

As 3D printing increases in popularity — for manufacturing and particularly for the prototyping of new products — resolving the throughput resolution trade-off is essential, Cleeman says, adding that MF3 is a major contribution to this effort.

Related Content

Concept Sneaker Boasts One-Piece 3D Printed TPU Construction

The Reebok x Botter Concept Sneaker Engineered by HP premiered at Paris Fashion Week, hinting at manufacturing possibilities for the future of footwear.

Read MoreQ&A With Align EVP: Why the Invisalign Manufacturer Acquired Cubicure, and the Future of Personalized Orthodontics

Align Technology produces nearly 1 million unique aligner parts per day. Its acquisition of technology supplier Cubicure in January supports demand for 3D printed tooling and direct printed orthodontic devices at mass scale.

Read MoreUnderstanding PEKK and PEEK for 3D Printing: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

Both materials offer properties desirable for medical implants, among other applications. In this bonus episode, hear more from Oxford Performance Materials and Curiteva about how these companies are applying PEKK and PEEK, respectively.

Read MoreActivArmor Casts and Splints Are Shifting to Point-of-Care 3D Printing

ActivArmor offers individualized, 3D printed casts and splints for various diagnoses. The company is in the process of shifting to point-of-care printing and aims to promote positive healing outcomes and improved hygienics with customized support devices.

Read MoreRead Next

3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More