The Value of Design for Additive Manufacturing (DFAM)

Design is the “value multiplier” when it comes to additive manufacturing.

Share

It can be hard to put a value on something, particularly the products a company makes or the parts someone designs. Cost, on the other hand, is easy. We know exactly how much material or a machine costs because we have to pay for it when we buy it. We can even get a reasonably good estimate for the cost to develop a product (or part) because we can count how many hours it took to engineer it, the cost to make prototypes, the cost to test each prototype, etc.

While these efforts add value to the product (or part) as it is being developed, quantifying that value is challenging. If the product (or part) does well in the marketplace, then we know that those efforts did, indeed, add value, but how much value was added at each stage of development remains open to interpretation.

If you read my column last month, I proposed a simple cost equation for additive manufacturing (AM) using laser powder bed fusion (PBF), one of the more popular AM processes right now for fabricating metal parts layer-by-layer. While reading about an equation may not excite you, that equation helps us unlock the value of design for AM, or DFAM as it is called in industry.

What do I mean?

The four main components of my AM cost equation are:

- Material.

- Build time

- Machine cost.

- Pre-/post-processing costs.

The more material needed, the more the part will cost; that one is easy. Build time and machine cost are a bit more coupled. Longer build time equates to higher cost, but a more expensive machine (e.g., a laser PBF system with multiple lasers) costs more to operate but offers a faster build rate. Of course, the maximum height of the part being built also adds build time (and subsequent machine cost) since the recoater takes ~10 seconds to spread a new layer of powder. This “dead time” and associated cost may seem trivial, but when you are spreading 1,000’s of layers, it can become a significant. Finally, pre- and post-processing costs were estimated at roughly 40% of the overall cost for an AM part based on recent industry averages according to MaterialsToday.

While lower powder prices and faster build speeds are great, it is easy to see why DFAM is the best value multiplier when it comes to AM.

With this model, the total cost of a metal AM part made using laser PBF can be estimated as the sum of material and machine costs, the latter of which is a direct function of the build time and layer recoating time, all divided by one minus the percentage of cost attributed to pre-/post-processing. To make the math easy for now, let us assume that pre-/post-processing cost is 50% so that we simply double the sum of material and machine cost to estimate the total cost of a metal AM part.

Savings From Other Factors

With this simple equation in mind, it becomes easy to quantify the value of DFAM in terms of the savings it imparts on the cost of a metal AM part. We can also compare that savings to the savings from other factors, such as reductions in the cost of powder feedstock or the productivity gains (and hence machine cost savings) from having more lasers or other improvements that increase build speed (e.g., higher laser power, larger spot size, thicker layers).

Let’s start with the latter two. If the cost of powder feedstock is reduced by 10-20%, then the material cost is also reduced by 10-20% as well. These savings translate directly to the total cost when we apply our pre-/post-processing multiplier but only in proportion to the ratio of material cost to machine cost. For example, if material cost and machine cost contribute equally to the part cost, which may be the case for an expensive material like titanium, then the total cost is reduced by 5-10% after applying our pre-/post-processing assumption since only half of the costs are attributed to the material.

How Does Build Speed Impact Cost?

The same logic applies to build speed. If the build speed doubles (or quadruples), then the build time (i.e., the laser exposure time) is reduced, but not by 50% (or 75%) because we still have the recoating time (i.e., time to spread powder for each layer). A short part (low z height) may see a 45% (or 70%) reduction in build time while a tall part (high z height) may only a see a 30% (or 60%) reduction instead of the 50% or 75% savings you might expect. Unfortunately, the hourly cost of a multi-laser PBF system may be 50-100% more than a single laser system, and the cost savings from reduced build time are not as high as you would expect. For the sake of argument, let us say doubling the build rate leads to 30% savings in machine cost for a metal AM part. As with material, this savings translates to the final cost in proportion to the ratio of material cost and machine cost after applying our pre-/post-processing multiplier. Assuming a 50/50 split, the final cost would be reduced by 15% in this scenario.

DFAM’s Impact on Cost

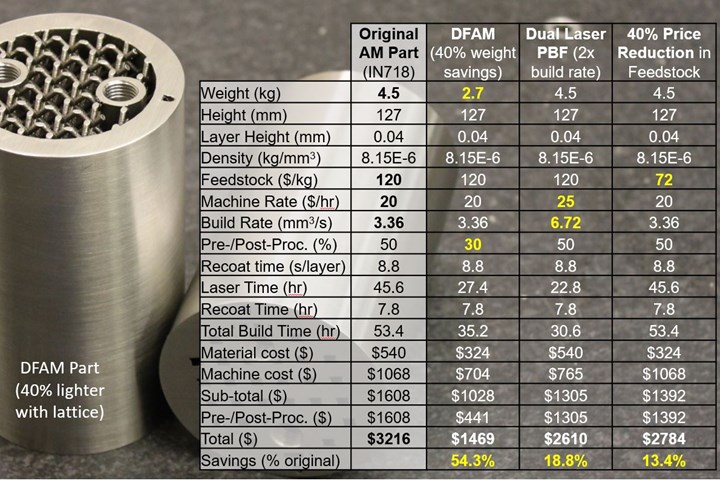

Now, how does DFAM compare? Well, if we use DFAM to lightweight a structure as is often done, then we save weight, which reduces material cost. It also means less volume to build, which reduces laser exposure and build time, lowering machine cost without increasing the hourly machine rate. DFAM also reduces the amount of support material needed, which further reduces material cost, build time, and machine costs. Assuming pre-processing cost lies in build set up and prep, not non-recurring engineering (i.e., design, optimization, analysis), then less support material means less build prep. More importantly, fewer supports means less post-processing costs because you do not waste as much time removing them after the build. As such, DFAM also reduces pre-/post-processing costs, decreasing the cost multiplier, saving more cost, and increasing the value of DFAM even more. The example in the figure shows how a 40% weight savings from using a lattice structure offers 3x to 4x the value compared to doubling the build speed or a 40% reduction in the cost of powder feedstock.

While lower powder prices and faster build speeds are great, it is easy to see why DFAM is the best value multiplier when it comes to AM. DFAM simultaneously reduces the cost of materials, the build time, the machine cost, and % of pre-/post-processing costs, compounding the savings many times over. More importantly, DFAM is something that you can control — you are not at the mercy of a powder supplier or a machine manufacturer to lower the price for you. In other words, if you are investing in AM, make sure to invest in DFAM (e.g., software, tools, training) as it will multiply the value of AM many times over.

Related Content

Velo3D Founder on the 3 Biggest Challenges of 3D Printing Metal Parts

Velo3D CEO and founder Benny Buller offers this perspective on cost, qualification and ease of development as they apply to the progress of AM adoption in the future.

Read More3D Printed Cutting Tool for Large Transmission Part: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

A boring tool that was once 30 kg challenged the performance of the machining center using it. The replacement tool is 11.5 kg, and more efficient as well, thanks to generative design.

Read More3MF File Format for Additive Manufacturing: More Than Geometry

The file format offers a less data-intensive way of recording part geometry, as well as details about build preparation, material, process and more.

Read MoreFlexible Bellows Made Through Metal 3D Printing: The Cool Parts Show #64

Can laser powder bed fusion create metal parts with controlled flexibility? We explore an example in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreRead Next

How 3D Printing Enables More Sustainable Designs (Video #2)

The circular economy needs the lightweight, optimized and efficient designs that only 3D printing can provide. More in this video, part of our series on 3D Printing and the Circular Economy.

Read More3D Printed Ceramics Serve As Both Bone Graft and Support

Bioceramics including tricalcium phosphate and zirconia have been used to replace and stabilize human bone in reconstructive surgeries. Now, 3D printing brings customization and new design opportunities to these medical devices.

Read MoreWhat Do These Flip Flops Say About Manufacturing's Future?: The Cool Parts Show #21

These 3D printed flip-flops are an example of mass customization, but they also hint at manufacturing's more sustainable, circular future. Find out why in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read More