The Challenges of Teaching Creativity in Additive Manufacturing

The extensive design freedoms offered in additive manufacturing can be paralyzing. With AM consistently pushing the boundaries of manufacturing, how do we teach people to take risks and be creative with AM?

Competitive design challenges provide external motivation for students to be more creative with AM compared to non-competitive, open-ended ones.

The design freedom of additive manufacturing (AM) is both a blessing and a curse. While many people are excited by the newfound freedoms that layer-by-layer manufacturing enables, an equally large number of people end up paralyzed by all of the freedom AM affords — where do I start?!?

I have seen this in my students as well as in industry, and some dichotomies have emerged. For instance, many engineering students struggle with all this freedom because the majority of their coursework focuses on problem solving, design specifications, meeting requirements, and avoiding failures. Meanwhile, artists and architects are taught to embrace ambiguity and uncertainty and challenge the assumptions and constraints for any problem they face. They search for opportunity while engineers satisfy constraints. Granted, this is an over-simplification to illustrate a point, but you can see how it predisposes students — and future employees — to how they will learn now and in the future.

Why Is A Hole Circular?

The same thing seems to happen in industry, although it manifests in a slightly different way. Those with, say, 20-plus years of experience designing parts for machining (or forging or casting) have intimate knowledge of the constraints associated with that process and have a tough time letting go of that knowledge to embrace the design freedoms of AM. I have literally seen people’s minds blown during AM workshops when they realize how many of their assumptions or biases are so intimately connected with their manufacturing experience. As I’ve said before, just ask someone, “Why is a hole circular?” and see how they respond.

But now that a hole can be any shape, what shape should it be? Therein lies the problem: we are used to designing to (and teaching about) so many constraints that once those constraints are removed or relaxed, we often don’t know where to start. Luckily, that is where a lot of engineering design education research is focused today, namely, how do we teach people to be creative with AM?

Study: Different Ways to Teach DFAM

Thanks to funding from the National Science Foundation, my colleagues Dr. Nick Meisel (project lead), Dr. Scarlett Miller, and I have been working with a Ph.D. student, Rohan Prabhu, to run experiments in our classes and labs to evaluate different ways of teaching design for AM (DFAM). Our studies thus far have focused primarily on the ordering and sequencing of DFAM knowledge and the nature and content of the ensuing design challenge.

We divide DFAM into restrictive (design strategies to mitigate the limitations of an AM process, e.g., thin walls, overhangs, warping/distortion, anisotropy) and opportunistic (design strategies to innovate with AM, e.g., part consolidation, lattice structures, topology optimization, mass customization). The design challenges range from open-ended (e.g., design a solution for hands-free viewing of a smartphone) to highly constrained (e.g., tolerances for mating interfaces, build time or material restrictions), and some are competitive in nature (e.g., the tallest and lightest weight structure will win) while others are not.

The work is still in progress, but with over 740 students participating thus far, some interesting results are starting to emerge — and they parallel what I’m seeing in the industry workshops that I have been running for the past five years.

Restrictive vs. Opportunistic

First and foremost, it is a lot easier for students to learn, use and recall the restrictive aspects of DFAM (i.e., the constraints) versus the opportunistic ones. This shouldn’t come as a surprise given how accustomed we have become to dealing with constraints. This is almost always the first thing that most practicing engineers want to know, i.e., what are the design guidelines for a given process so that I can make sure my part doesn’t fail. This is the same mentality that exists for any other manufacturing process, and it is one of the toughest to break when it comes to AM.

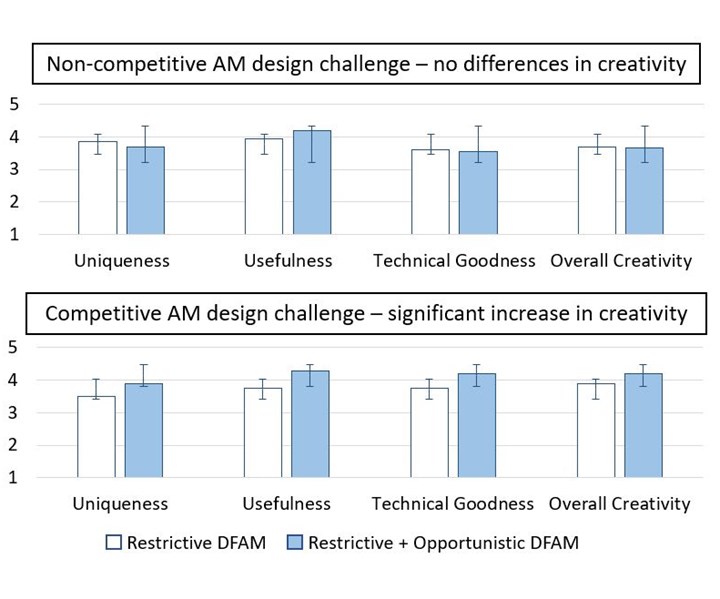

Second, we are not seeing huge gains in creativity once the opportunistic aspects of DFAM are introduced as we had initially thought. We have looked at the ordering of restrictive versus opportunistic, which gets introduced first versus second, in an open-ended challenge, and we are not seeing significant differences in our metrics for usefulness, uniqueness and overall creativity. Technical goodness (i.e., the feasibility of a successful print) does improve, but that is mostly attributed to learning the restrictive aspects of DFAM.

Technology Push vs. Market Pull

What seems to be a larger driving factor for using the opportunistic aspects of DFAM is the nature of the design challenge itself. In an open-ended challenge, the motivation is intrinsic to leverage the design freedoms of AM whereas in a more constrained problem, or better yet a competition, the motivation is external to be creative to reduce weight, build time or realize a clever solution to a complex problem.

Again, this parallels what I’m seeing in industry: is AM being driven within the company by a passionate few (i.e., technology push) or is it being used to solve challenging problems in creative ways while delivering new value (i.e., market pull)? The former leads to a burst of excitement that will fade away if it is not connected to the latter, and the latter will be difficult to achieve if the mentality focuses solely on design guidelines.

The willingness to be creative with AM on an existing project on which you will be evaluated is directly linked to the company’s culture of failure.

Underlying all of this is the culture of failure within the classroom or the company. If the design challenge is tied to a grade, then students will take fewer risks and be a lot less creative when it comes to AM. Same thing happens in industry as well. The willingness to be creative with AM on an existing project on which you will be evaluated is directly linked to the company’s culture of failure.

The attitude toward failure in an aerospace or medical company, for instance, is very different from a consumer products or industrial design firm, and while no one likes failure, those willing to embrace and learn from failures are also the ones pushing the boundaries and learning how to be the most creative with AM.

Related Content

3D Printed Cutting Tool for Large Transmission Part: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

A boring tool that was once 30 kg challenged the performance of the machining center using it. The replacement tool is 11.5 kg, and more efficient as well, thanks to generative design.

Read More3D Printed Lattice for Mars Sample Return Crash Landing: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory employs laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing plus chemical etching to create strong, lightweight lattice structures optimized to protect rock samples from Mars during their violent arrival on earth.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MoreVelo3D Founder on the 3 Biggest Challenges of 3D Printing Metal Parts

Velo3D CEO and founder Benny Buller offers this perspective on cost, qualification and ease of development as they apply to the progress of AM adoption in the future.

Read MoreRead Next

Video: Inside the Penn State Additive Manufacturing Master's Program, Part 4

Kevin White, mechanical engineer at the Naval Nuclear Lab and student at Penn State, shares how a higher education in AM provides benefits beyond technical training.

Read MoreInside the Penn State Additive Manufacturing Master’s Program, Part 1

PSU's engineering master's degree in additive manufacturing and design offers students and manufacturing professionals a higher education in a continuously maturing field.

Read MoreProfilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read More