“We’re sintering experts,” says Tom Freemer, plant manager at Alpha Precision Group (APG). “If it doesn’t involve sintering, we can’t set ourselves apart with it. We’re not interested.”

Tom Freemer, plant manager, shows me around APG’s facility for metal injection molding (MIM) and metal 3D printing. Trays of both molded and printed green parts are staged here for sintering, which the company considers its core competency.

Fortunately, APG has found there’s plenty of metal part production that requires this specialization. The company as a whole has been involved in conventional powder metallurgy processes including press and sinter and metal injection molding (MIM) for decades. But within the last few years, Alpha Precision Group has been realizing new opportunities with an emerging class of additive manufacturing (AM) processes that also rely on sintering.

Sintering is the operation that parts produced by APG have in common. This furnace at the Ridgway facility is used to sinter both MIM and 3D printed green metal components.

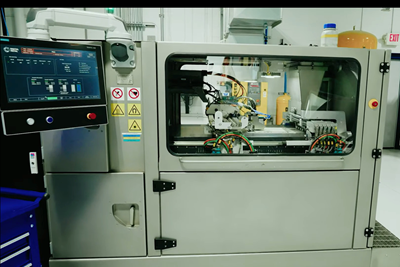

Among the technologies available at the company’s Ridgway, Pennsylvania, facility today are bound metal deposition (BMD) via a Desktop Metal Studio System, binder jetting with one Digital Metal machine and several Desktop Metal Shop Systems, and MoldJet 3D printing via the Tritone Technologies Dominant machine.

In each case, the 3D printer itself only forms the green part; additional processing, including a visit to a sintering furnace, is necessary to fuse the material together — the same requirement for the other powder metal parts made by the company. But the 3D printing capacity is opening new avenues for parts to reach production, whether that is through conventional methods or additive manufacturing at scale.

Metal injection molded parts like these are one of APG’s specialties. Its sinter-based additive manufacturing capability supports MIM by enabling faster, more flexible design iteration; bridge production; and full production for certain parts.

The Bridge to MIM

APG’s journey toward additive manufacturing, Freemer says, really started with MIM. The company acquired Precision Made Products, a metal injection molding specialist in 2016, which prompted a search for ways of quickly and economically developing parts for MIM before creating hard tooling. In many cases the company relied on machining to iterate and prove out designs before cutting molds, a process that could be time-consuming and complex, and did not always result in a one-to-one transfer to MIM.

In 2018, the company added its Desktop Metal Studio system, a desktop-sized BMD printer that extrudes filament carrying embedded metal powder to produce green metal parts. Initially, this machine was used to provide more durable jigs and fixtures for machining operations than what the company had previously been 3D printing in polymer. (One of those early workholding successes, a chuck jaw developed for machining cam gears pictured below, has actually evolved into a business opportunity in its own right.)

This metal 3D printed chuck jaw replaces a previously machined version that was heavier and provided more clamping force than was necessary. APG optimized the tooling to reduce its weight by more than 70% and clamping force by half.

But BMD also introduced Alpha Precision Group to the benefits of design iteration through metal 3D printing, as a development step before transferring production to MIM.

Using the Studio system, and Desktop Metal Shop systems for binder jetting added in 2020, APG began to apply metal 3D printing to iterate parts bound for metal injection molding. Compared to the previous strategy of prototyping through machining, BMD and binder jetting enabled the company to prototype more affordably and to develop designs that more directly translate to the MIM process.

Up to 85% of the MIM products made at APG are for the firearms industry. These components for a biocompatible firearm (which can only be removed from its docking station by a specific individual) went through three design iterations through metal binder jetting before tooling was made for MIM.

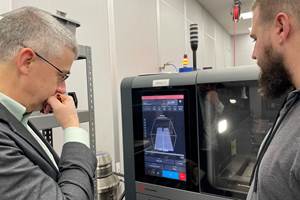

The Digital Metal machine is capable of printing with thinner layers than the company’s other binder jetting platforms, but results in a trade-off in speed.

APG was acquired by Nichols Portland Inc. (NPI) in 2022 and has continued to add to its capabilities with machines from other vendors, becoming an early adopter in North America for both the Digital Metal P2500 binder jet platform and the Tritone Technologies Dominant printer for the Moldjet process.

The former machine (pictured to the right) offers improved surface finish compared to the company’s other binder jetting options, with 42-micron layers possible. This resolution comes with trade-offs (each layer can take a minute or more to print) but for medical devices and applications where appearance matters, the added print time can be justified.

The additive manufacturing team at APG is small. Plant manager Tom Freemer (right) and manufacturing engineer Joe Taylor (left) devote about half their time to AM; Danielle Swanson (center) is the company’s additive engineering technician and only full-time additive-focused employee. Also visible in this photo (from left to right) are the Tritone Dominant system, Desktop Metal Studio for BMD and two Shop systems for binder jetting.

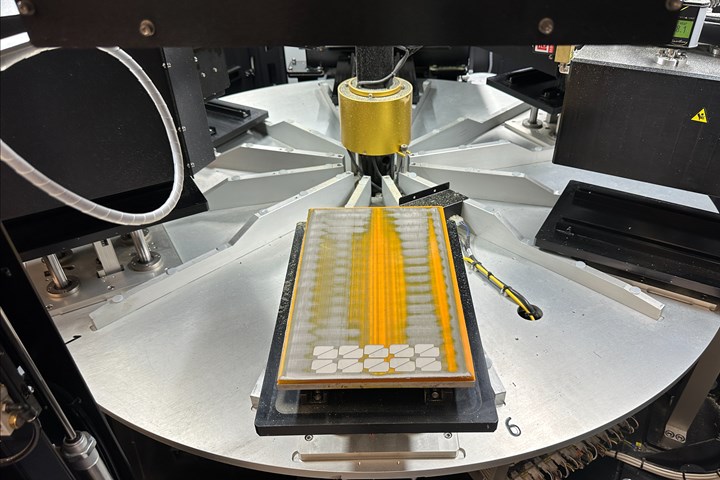

The Tritone machine, meanwhile, is used to develop parts with complex geometries that might be difficult to create without support structures. The multi-station carousel system begins each layer by 3D printing a wax mold which is then filled with a specialized blend of metal powder and binding agents. Each layer is dried and hardened, and then inspected before the process repeats. Post-printing, the support wax is removed with thermal processing and solvent; parts are then sintered in a batch furnace.

The Dominant machine supports up to six build trays running simultaneously, offering speed and productivity that also makes it attractive for rapid design iteration. Green parts built this way exhibit isotropic shrinkage during sintering much more like traditional MIM parts, making it fairly straightforward to convert a MoldJet part to the higher-scale process.

The Tritone Dominant machine operates as a carousel, with stations for depositing and machining the orange wax material that forms the part mold, filling the tool with metal paste, drying it, and inspecting each layer before repeating the process.

Sinter-Based Additive Manufacturing for Production

While the binder jetting platforms like the Shop System are primarily used for developing parts that will transition to MIM, APG is increasingly finding applications where metal 3D printed parts become end-use. The Shop system, Freemer says, can be used for production runs in the hundreds, while the Tritone platform is useful for fulfilling orders ranging to the thousands.

Recent examples of parts that have gone into production with metal 3D printing include the two halves of a shell for a training grenade (one half is pictured above). Creating tooling to mold the two halves of the component would cost up to $50,000, a high price tag given the quantity needed. Instead, APG has used binder jetting to produce several runs of 150 parts each more economically.

This banjo capo is a niche product that is more economical to produce through binder jetting than via MIM.

Another binder jetting application is this banjo capo, an accessory used by banjo players to easily change the key of their playing by clamping down on the instrument’s strings. APG expects to produce only about 1,000 of each part, making 3D printing the best way to deliver this niche product. Manufacturing the parts this way is proving to be cheaper than either molding or machining, and has made it possible for the customer to incorporate its logo without adding complexity to manufacturing.

Finding opportunities like this continues to be a case-by-case evaluation.

Right now Alpha Precision Group has more metal 3D printing production capacity than it typically can fill, which has led the company to offer its services through online providers like Hubspot. This work can be useful, but it isn’t ideal for finding the best applications of the technology which in APG’s experience comes from working closely with customers in the early stages of a product’s design. That ground-floor involvement is particularly useful because most customers aren’t aware that they could or should be using additive.

“I’m not sure we’ve seen a real ‘lightbulb moment’ with a customer yet,” Freemer says. “It’s difficult to break the mindset to get them to consider AM.”

Still, APG is able to bring clients around by demonstrating advantages of the processes including speed, design freedom, and the chance to avoid or put off purchasing tooling. Ongoing growth in this part of the business is leading the company to expand its equipment further — it expects to add a Lomi solvent debinding system later this year — and, Freemer says, could result in APG mixing its own MoldJet material by combining the MIM powders already on hand with additives from Tritone. However business comes, APG intends to stay true to its roots in sintering.

Related Content

Freeform: Binder Jetting Does Not Change the Basics of Manufacturing

Rather than adapting production methodologies to additive manufacturing, this Pennsylvania contract manufacturer adapts AM to production methodologies. In general, this starts with conversation.

Read MoreVideo: Binder Jetting Production Workflow at Freeform Technologies

Additive manufacturing via binder jetting includes a sequence of downstream steps. During a visit to the Pennsylvania metal 3D printing part producer, I had the chance to walk through this process.

Read MoreVideo: Multimodal Powders for Metal 3D Printing

Rather than uniform particle diameters, multimodal powders combine particles of different sizes. In this video, how and why Uniformity Labs produces multimodal metal powders for additive manufacturing.

Read MoreMultimodal Powders Bring Uniform Layers, Downstream Benefits for Metal Additive Manufacturing

A blend of particle sizes is the key to Uniformity Labs’ powders for 3D printing. The multimodal materials make greater use of the output from gas atomization while bringing productivity advantages to laser powder bed fusion and, increasingly, binder jetting.

Read MoreRead Next

From Polymer Tooling to Metal Production Via 3D Printing

As Azoth has adopted new additive manufacturing technologies, its work has transitioned from tooling to production parts for automotive, medical and defense.

Read MoreBinder Jetting Follows in Footsteps of Metal Injection Molding

For Smith Metal Products, additive manufacturing helps MIM customers finalize the design, but production opportunities are waiting.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)