Shoe Manufacturing at Flowbuilt Is Reshored and Reimagined

The shoe store of the future is more like a digitized tailor’s shop than a warehouse. Flowbuilt Manufacturing is the flexible contract manufacturer that can serve this vision, using both 3D printing and injection molding.

In the shoe store of the future, a woman steps onto a scanner. The machine takes images of her feet from all sides, capturing the geometry of her arches, her toes, her soles. She walks across a mat that records the details of her gait, noting perhaps that one heel lands a little harder, one foot turns a little to the outside. She steps in front of a monitor, and, seeded with the biomechanical information she’s just provided, the computer presents a selection of running shoes recommended for her high arches and slightly overpronated gait, in precisely the right sizes to fit her feet.

But there is more. Alongside the off-the-shelf shoes, the kiosk presents other choices. The woman can order a set of custom insoles made from her scan data to make those off-the-shelf shoes fit better. Or, she can select one of the shoe options presented and have the pair made with her own geometry built right into the midsole. Within days, she could be lacing up brand new running shoes with all the style and flair of her favorite brand, but with a fit that is uniquely tailored to her feet.

This is a different way of buying footwear, one that relies on digital technology and personalization instead of choices presented as-is. A trip to the shoe store becomes less like a hunt through a warehouse and more like a visit to a digitized tailor’s shop. In this model, the customer is not overwhelmed by choice; she sees only the shoes that will fit her best, and options for improving that fit. She does not need to try on a dozen different pairs to find the shoe that fits, and so the store does not need to be overstocked with inventory to allow for this. The shoe store of the future is lean, sleek and streamlined, but it also needs something invisible to its customers: A contract manufacturer with the flexibility and capability to make these custom shoes locally and on demand. It’s a role that Flowbuilt Manufacturing was literally designed to fill.

The shoe store of the future has fewer shelves and less inventory. Instead of trying on many pairs of shoes, a customer could use scan technology to identify the brands and styles that will fit, and possibly have insoles or complete shoes made to order. Photos: Flowbuilt Manufacturing

An Off-Ramp to Personalized Production

“We brought together these people with all this experience, who have made shoes in every possible way, and built this model from the ground up,” says Chuck Sanson, Flowbuilt Manufacturing’s director of business development. “We asked, ‘If you had the opportunity to start over with the experience you have today, what would you do differently?’”

Flowbuilt’s parent company Superfeet is a specialty shoe and insole manufacturer with a focus on footwear for comfort and pain relief, in business since 1977. But Flowbuilt itself was established much more recently in 2018, bringing together a founding team of professionals from contract manufacturing, 3D printing and the footwear industry to come up with a better way of making shoes within the United States. The catalyst for its launch was Superfeet’s 2017 partnership with HP to produce a line of custom-made 3D printed insoles as part of its Fitstation initiative. Fitstation uses software from HP along with pressure plates and biometric scanning technology developed by RSScan to capture and analyze data about a consumer’s feet and gait that could be used to create unique insoles for each foot. The problem, however, was finding a supplier to produce those insoles.

RSScan pressure plates and biometric scanning technology are the core of the Fitstation platform, which makes it possible to capture the data needed to produce custom footwear.

“Flowbuilt initially was an off-ramp of that partnership, because there was nobody that could create these products,” Sanson says. “Personalized products are not something that you can effectively manage from 6,000 miles away. We needed a strategy that puts a manufacturing hub closer to consumers.”

This manufacturing “hub” was built next door to Superfeet’s facility in Ferndale, Washington. The custom insoles were developed to be manufactured with HP’s Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) technology which was the starting point for the facility. Flowbuilt today has three of these polymer 3D printers plus the necessary postprocessing and powder handling equipment.

Flowbuilt relies on its three Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) polymer 3D printers and this postprocessing station for manufacturing shoe components like insoles as well as mold tooling.

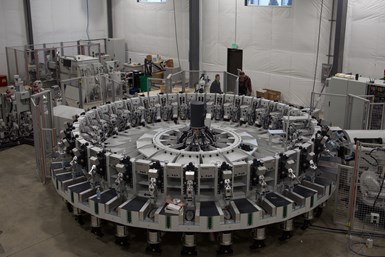

But it is also equipped with injection molding capability in the form of a Desma direct-attach machine — a rotary injection molding system that can hold multiple sets of tools to inject the polyurethane midsole in between a shoe’s outsole and upper.

The company’s robot-tended Desma injection molding system holds enough molds to make 15 different shoe variations at once. Each mold rotates past a single injection point where it is filled with precisely the right amount of material.

With these capabilities plus some automation, Flowbuilt has the technology in place to manufacture completely custom shoes. Superfeet insoles and shanks remain a significant part of its production, but the company’s capacity is not held captive by its parent nor is its vision limited solely to these products. Flowbuilt is now pursuing partnerships with other brands to help introduce custom shoes in a number of verticals. Its first such partner is running shoe company Brooks, which has launched a line of customized Genesys shoes based on Fitstation data capture.

“Although Flowbuilt started as a development center and a proof of concept for personalized products, it’s quickly grown and its value has been demonstrated in a full contract manufacturing model with 3D printing,” Sanson says. “We are a scan-to-production partner for Fitstation, and also a contract manufacturing partner for in-line goods.”

Automated, Local Footwear Manufacturing

It’s difficult to appreciate just how innovative Flowbuilt Manufacturing is without the context of the wider shoe manufacturing industry. The Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America (FDRA) reports that in 2019, 2.5 billion pairs of shoes were imported to the U.S., an average of 7.5 pairs per person. Many of those shoes were made in Asian factories, particularly in China and Vietnam. It is not uncommon for brands to design and develop a shoe in the U.S. but then contract with factories overseas for production, often turning over even mold design to these manufacturers. (While this model works when business runs as usual, it introduces some challenges when international trade becomes strained as during the coronavirus pandemic, as Flowbuilt and others share.)

The reasons for footwear companies to make their products overseas boil down to the usual suspects — primarily ramp-up speed and abundant labor available at an affordable price. The latter is particularly important given the amount of handwork that still goes into making most shoes. Many athletic shoes are made with EVA foam, for instance, because of its light weight and durability; however, the material requires hand postprocessing and doesn’t bond readily to other materials.

“We can’t compete on speed with China,” says Chuck Sanson, Flowbuilt Manufacturing’s director of business development. “We’ve had to find other points of differentiation.”

“With EVA foam, you mix the material and pour it into a mold where it expands, almost like spray foam,” Sanson explains. “You trim it, and the foam becomes the midsole. Then you have to use a cold cement process to attach the upper and the outsole, basically creating a sandwich. You can’t put a lot of automation into that process — it could take 100 people on a finishing line to make that shoe.”

Flowbuilt, on the other hand, has closer to 50 employees total, not enough to do the kind of high-touch shoe manufacturing that takes place in Asia at breakneck speeds. “We can’t compete on speed with China, so we’ve had to find other points of differentiation,” Sanson says.

One of those points is its more automated process, enabled by the rotary injection molding system mentioned above. The Desma machine is tended by a robot, and can hold enough molds at once to produce 15 different pairs of midsoles — about the average number of sizes in a typical shoe line. The machine rotates each mold past a single injection point, injects it with a computer-controlled amount of material, and ejects the finished piece within about 12 seconds. The ability to manufacture a high-mix batch with a single, automated machine gives Flowbuilt flexibility to serve multiple customers and make small runs quickly.

Flowbuilt Manufacturing’s robot-tended Desma system rotates each mold past a single injection point. Production can continue while parts cool and molds are changed out, supporting the kind of low-volume, high-mix shoe manufacturing the company was designed for.

But this system is particularly valuable because it can do more than just make the midsoles, as a result of the material choices Flowbuilt has pursued. Rather than EVA, Flowbuilt molds its midsoles with polyurethane — a material that can be chemically bonded with other shoe components. With the Desma machine, Flowbuilt can place a shoe upper in each mold (including a custom 3D printed insole or shank if called for) and injection mold a polyurethane midsole that will bond directly to it. With this process there is no trimming, no cold cement and greatly reduced hand labor.

Using the direct-attach machine, Flowbuilt Manufacturing can inject polyurethane between 3D printed insoles and other shoe parts, bonding them together without any manual gluing or trimming steps.

Of course, this automated system still requires tooling to mold the midsoles. A set of steel or aluminum molds costs somewhere in the neighborhood of $7,000 to $10,000, and that’s just for one size in a shoe line. 3D printing is a win here too — Flowbuilt Manufacturing has found proprietary methods for building short-run tooling with its Multi Jet Fusion printers. A set of these molds can be 3D printed from nylon and installed into the Desma machine within about a day, allowing for a rapid turnaround on custom shoes.

“We took a traditional business and fundamental machinery, and dropped innovation on top of it,” Sanson says. “Current footwear factories would have a difficult time bringing in an innovation project to figure out how to 3D print tooling. They’d have to make the investment in the 3D printers without seeing much of a return. In our case, the 3D printers have been operating almost continuously from Day One making parts so we can derive revenue from them and build the tooling we need.”

Branded Footwear, Personalized

Superfeet’s ME3D sandals have custom 3D printed heel cradles embedded inside for support and stability.

Today Flowbuilt Manufacturing makes two custom products for Superfeet, 3D printed insoles and a personalized version of its Aftersport slides under the ME3D brand. Both items are tailored to the wearer based on data gathered through Fitstation kiosks. Flowbuilt’s customer breakdown is constantly shifting, but Sanson puts it at about 10% Superfeet work (custom insoles, braces, shanks) and about 90% contract brand manufacturing. R&D, he notes, is split about 50-50 between these two pursuits, because custom footwear tends to require proportionately more development time.

As its partnerships with Superfeet and Brooks suggest, Flowbuilt’s ambition is not to develop or sell its own line of products. Instead, the company is a neutral contract manufacturer committed to helping companies reshore shoe manufacturing closer to U.S. customers, and bringing more brands onto the Fitstation platform for customized shoes. The company is effectively the mediator between a customer’s individual data and the brand’s design.

“The challenge is not ‘Can I make a shoe custom to you?’ but ‘How do I enable that shoe to be custom and also express the personality of the brand?’”

“The challenge is not ‘Can I make a shoe custom to you?’ but ‘How do I enable that shoe to be custom and also express the personality of the brand?’” Sanson says. “We spend an awful lot of time working on bringing those two aspects together to understand how personalization becomes real, and how the product also meets the image of the brand that’s offering it.”

The Fitstation platform is brand agnostic as well and could support many different styles of footwear, Sanson says. Getting direct competitors to list their shoes side by side through Fitstation can be tricky, though, and so the project instead has focused on filling different footwear verticals. Brooks is the first partner in the running space; other footwear segments that could be added include outdoor, work and industrial.

The benefits to the brands? Aside from a fast and cost-effective way of adding personalized shoes to a brand’s offering, Flowbuilt Manufacturing sees its value add in a new model for doing business.

“We’re changing the fundamental nature of the way brands work with manufacturers,” he says. “We work in an open book. All of the tooling, all the materials, everything — that’s all owned by the brand. It’s a different way of doing business.”

For Flowbuilt, it’s not about choosing 3D printing over injection molding. It’s about utilizing both technologies together to deliver a more stable, sustainable method of footwear manufacturing closer to where customers are.

Brand ownership is about more than protecting IP or reshoring production; it’s also about bringing manufacturing closer to customers. Local production will be the key to enabling custom products made to order because without it, the shoe store of the future can’t deliver a tailored experience in a timely fashion — but there are lessons for standard products too. A stretched supply chain may save in manufacturing cost, but a shorter chain that distributes manufacturing reduces lead time, limits shipping and is more sustainable, both in the environmental and business senses.

“We can help brands lessen their dependence on outsourcing and de-risk their supply chains,” Sanson says. “We can give them a real, viable option to make a significant proportion of their shoes closer to the customer. That’s fundamentally better for the environment and for commerce. You can be profitable by manufacturing closer to where you live, to where your customers are, if you look at it through a different lens and have more ownership of the process yourself.”

Related Content

What Is Neighborhood 91?

With its first building completely occupied, the N91 campus is on its way to becoming an end-to-end ecosystem for production additive manufacturing. Updates from the Pittsburgh initiative.

Read MoreConocoPhillips Sees Oil and Gas Supply Chain Opportunity With Additive Manufacturing

Production of parts when needed and where needed can respond to the oil and gas sector’s multibillion-dollar challenge of holding parts in inventory. The supply chain benefit will justify additive even before the design freedoms are explored.

Read MoreVideo: 5" Diameter Navy Artillery Rounds Made Through Robot Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Instead of Forging

Big Metal Additive conceives additive manufacturing production factory making hundreds of Navy projectile housings per day.

Read MoreWhy AM Leads to Internal Production for Collins Aerospace (Includes Video)

A new Charlotte-area center will provide additive manufacturing expertise and production capacity for Collins business units based across the country, allowing the company to guard proprietary design and process details that are often part of AM.

Read MoreRead Next

Gantri’s 3D Printed Luxury Lighting Brings Designers Closer to Consumers

The San Francisco startup is changing designer lighting with a designer-forward online marketplace and just-in-time delivery enabled by 3D printing.

Read MoreThe New Normal? Resilient Supply Chains with 3D Printing

We were already headed toward expanded adoption of 3D printing, in HP’s view, when the coronavirus hit. The pandemic’s disruption will only get us there faster.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)