Three major sectors seeing significant transformation from additive manufacturing are, of course, Aerospace, Medical and Tooling. Ready and waiting to join that list is Oil and Gas. But in the case of this latest major adopter, the force of the adoption is different. AM arguably pushed its way into the other sectors, asserting new possibilities for each. With this newest industry, the force is a pull. Oil and Gas has a multibillion-dollar problem it expects additive manufacturing to address.

That problem is replacement parts, including the lead time for conventionally manufacturing critical components used in oil and gas operations, and the inventory costs that come from storing parts to try to avoid this wait. “The oil and gas industry has billions of dollars of spare parts in inventory at any given time,” says Carlo De Bernardi, additive manufacturing lead for oil and gas producer ConocoPhillips. He believes AM can dramatically shrink this cost by providing the ability to print components as they are needed, even where they are needed. Thus, for the oil and gas sector, additive’s value is not primarily about part design. AM is instead seen as the enabler to a new and more efficient supply chain.

I recently spoke with De Bernardi about this.

“We are not a manufacturer. We don’t make the equipment,” he says. ConocoPhillips uses the equipment, and this is difficult enough — the nature of oil and gas means the work must be done where reserves are located, generally in remote parts of the world. Demanding applications for manufactured parts lead to frequent part replacement in these faraway places. The parts themselves might be straightforward; De Bernardi’s main area of concern is piping and valves. Yet components are often made of aerospace alloy, and getting them produced through casting or forging plus machining, then delivered to an oilfield in northern Alaska, might result in a wait of nearly a year. Hence the need for inventory as a buffer.

De Bernardi has moved from additive’s critic to its champion. When he first encountered AM years ago, he considered it too great a risk. “We have a codified approach to qualifying parts made through casting and forging,” he says. AM was nowhere near as mature as those processes. It still isn’t, but the rapid advance in capabilities and understanding of AM has brought additive to the point of being able to make needed oilfield parts to a level of performance and confidence commensurate with established processes.

In 2019, De Bernardi brought together a group of nearly 200 manufacturing experts in and out of the oil and gas industry to help him author a proposal to the American Petroleum Institute (API) to create this industry’s first standard for qualifying metal AM parts. His success with this proposal suggests the first of five points about AM for oil and gas parts that struck me in our conversation:

1. Standards are needed, but coming fast

The industry needs its own standards, separate from those for aerospace and medical. However, the widespread recognition of additive’s potential in this industry has spurred standard development. The metal AM parts standard, API 20S, was published within two years of De Bernardi’s proposal. A standard for polymer AM components, API 20T was published a year later.

2. Supply chain flexibility is the big win

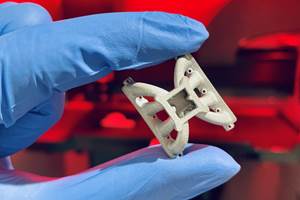

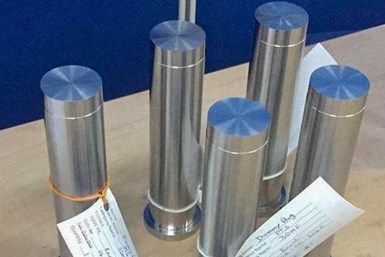

Burner plugs made of Inconel 718 can take 30 weeks to source. Making the parts via AM can reduce this time to less than two weeks. Photo: ConocoPhillips

Part geometry is not always the win that is needed. Example: A burner plug is a simple component, essentially a 3-inch-diameter solid cylinder of Inconel 718. But this component can take 30 weeks to source to the Alaska North Slope where it is needed. Additive manufacturing offers the chance to produce the plugs and deliver them in under two weeks. A network of additive providers making parts such as this could replace warehouses keeping parts in inventory, offering dramatic cost savings even before further cost savings are explored through design changes made possible with AM.

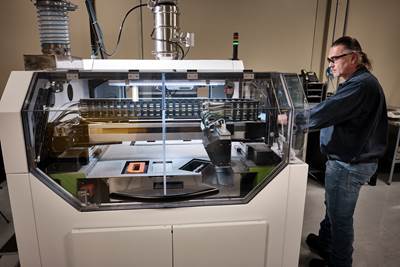

3. AM is a broad term entailing various processes

“We spent a lot of time on laser powder bed fusion,” De Bernardi says. “We might have been better starting with directed energy deposition. We make a lot of big stuff.” And the possibilities of DED are advancing.

In particular, DED via wire arc additive manufacturing is appealing because of the range of established materials it allows given its nearness to conventional welding. Indeed, the process might have been already close to the qualification standards needed. “Rather than ‘additive manufacturing,’ we could have seen this as structural welding,” he says. The qualification requirements of structural welding are to some extent already defined.

The nature of oil and gas work is that critical replacement parts have to be delivered to remote locations such as the Alaska North Slope, seen here. Photo: ConocoPhillips

4. For AM, local manufacturing is a way in

“Wherever we do business, we would like to be able to manufacture locally,” he says. OEMs in many industries increasingly want this. For oil and gas producers, this aim is difficult: Valve parts are cast, and it is not practical to establish numerous new foundries. Establishing AM facilities is a different matter. With additive, ConocoPhillips can have a supplier network that is more locally sourced than ever before, and this benefit alone offers a compelling reason to urge additive forward.

5. Suppliers need to know the industry

This last point describes arguably the biggest gulf ConocoPhillips still faces in developing an AM supplier network. Today, there are oil and gas manufacturing suppliers; there are additive manufacturing suppliers. They are two different things, and somehow, one must become the other.

“We need suppliers that can understand our supply chain and their role in it,” De Bernardi says. “If you are intent on bringing disruption from the start, this won’t take off.” Change is coming and suppliers will enable it, he says, “but you need to know the rules before you can change the rules.”

Related Content

For Coast Guard, AM Adoption Begins With “MacGyver-ish” Crew Members Who Are Using 3D Printing Already

AM suits the Coast Guard’s culture of shipboard problem-solving, says Surface Fleet AM lead. Here is how 3D printers on ships promise to deliver not just substantial cost savings but also an aid to crew capabilities and morale.

Read MoreUPM Additive Solutions and Authentise Develop Vendor Managed Inventory Solution for Additive Manufacturing

The Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) solution for additive manufacturing streamlines inventory management, ensuring that critical materials are always available and minimizing the need for manual intervention.

Read MoreWürth Additive Group Launches Digital Inventory Service (DIS) Platform to Simplify Supply Chains

The DIS enables distributed, on-demand manufacturing for OEMs and companies of all sizes through secure data transfer and detailed production processes.

Read MoreIncus Successfully Tests Lithography-Based Metal Manufacturing for Lunar Environment

The project aim was to develop a sustainable process that uses lunar resources and recycled scrap metals (eventually contaminated by lunar dust) to produce spare parts on-site which could help and enhance human settlement on the moon.

Read MoreRead Next

The Way Ahead for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing

Tooling today, production tomorrow. The capability will advance as value is increasingly seen in lead time savings and design opportunities. Parts that today are cast offer a particularly promising application for a process that is “welding, except not.”

Read More3D Print or Stock? A Model for Spare Parts

3D printing provides a way of manufacturing spare parts on demand, in situ. But is it always the best solution? A new model from a Duke University professor aims to help companies make these decisions.

Read MoreCutting Tool Maker Succeeding With 3D Printed Carbide for Oil/Gas and Other Applications

Powders, parts and products are different ways the company is advancing with AM. Carbide and tools are separate areas of success.

Read More