How Thin Can I Make My 3D Printed Part?

Be smart and prototype fast when developing design guidelines for AM.

Share

Read Next

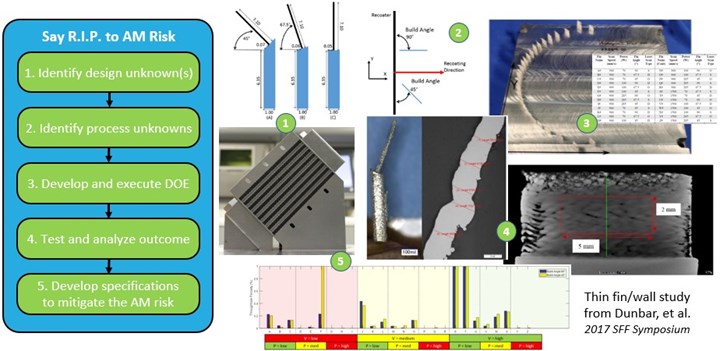

Illustration of steps undertaken by Dunbar, et al., to develop design guidance for thin fins used in AM heat exchangers.

Photo Credit: Dunbar, et al.

Rapid prototyping has been the predominant use case for 3D printing and additive manufacturing for over 30 years. With metal AM, being smart and fast is even more important when it comes to prototyping, given the cost of materials, machines and post-processing. Consequently, I introduced the notion of Rapid Intelligent Prototyping (R.I.P.) previously. In this column, I intend to dive deeper and share an example that may spark an idea or trigger a new way of thinking for users developing AM parts for production.

Consider a heat exchanger — a very “hot” application for AM right now (sorry, couldn’t resist the pun). Typically these are made by stacking layers of perforated or finned sheets on top of one another and then welding or brazing them together into an assembly. It is easy to make the sheets, it is easy to make the fins or perforations in the sheets and it is easy to stack them together into an assembly. The end result, though, is often a large, boxy structure that must be “designed around” if you want to incorporate it into a larger system. Look no further than the radiator in front of your car’s engine to see what I mean.

With AM, we can now reimagine what a heat exchanger looks like. For instance, it can be designed to conform to (that is, wrap around) the shape of the system or component that is being cooled (for example, a hot cylindrical pipe). An aircraft engine oil cooler, for example, no longer needs to look like a metal shoebox; instead, the surface area can be redistributed and made to fit within the natural spaces and gaps within an aircraft engine if you employ AM.

In redesigning such a heat exchanger, users may start wondering: How small can I make a wall or fin and still print it? In what orientation should they be arranged? What cross-section should the fins have? Can I vary the fin cross-sections, and if so, what is the best configuration for each fin and the fins as a whole? What is the impact of surface roughness on the fins? What if the fins are not fully dense; would a porous fin create more surface area and be more efficient?

These are but a few of the questions one encounters when (re)designing heat exchangers for AM. While they may appear straightforward and easy to answer, they are not, particularly when it comes to metal laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF). The interactions between the material feedstock being used, the processing conditions in the machine and the design geometry and print orientation are so tightly coupled that it is impossible to guess — and currently too complex to fully model and simulate — the best conditions for each. Worse, since designers have never had the ability to make such complex geometries and internal passageways before, the heat transfer coefficients and friction factors that they look up in a table or chart to size a heat exchanger do not exist. So now what?

Rapid Intelligent Prototyping

Enter what I call Rapid Intelligent Prototyping (R.I.P.) to address each unknown in a smart and efficient way — in this case, to develop AM design guidelines for a thin wall or fin and, more importantly, mitigate the risk of it not printing or failing during use. What follows is a brief synopsis of an R.I.P.-like study (although they did not call it that) carried out in our lab by Alex Dunbar under the supervision of Ted Reutzel, director of CIMP-3D.

As described by Dunbar, et al., any such study begins by defining the unknowns or uncertainties of interest. In this case, there were two:

- Fin thickness and fin angle.

- The build orientation of each fin with respect to the recoater blade. This is because a very thin wall built parallel to a recoater can be easily damaged depending on the L-PBF system.

The team also had the ability to vary some of the process parameters, opting to consider a range of scan speeds, laser powers and exposure strategies. Experienced AM users know that varying process parameters is critical when pushing the limits on printable geometry — look no further than Velo3D or SLM Solutions, two L-PBF companies that mastered the use of process parameters to enable support-free metal AM.

With multiple design geometries, build orientations and process parameters to vary, it is time to use design of experiments (DoE) techniques to vary different combinations of each variable intelligently to maximize the information gained with minimal effort and cost. Users also need to consider how many builds to run as part of the study, as these add time and cost. Finally, users must consider how to measure the output of each build outcome, as it is easy to get overwhelmed with too many samples given the capabilities of AM — another area in which to be “intelligent” when using R.I.P. to address unknowns and mitigate risks.

Once the DoE has been planned, the build — or builds — get executed, and the results are analyzed to identify the best combination of settings for, in this case, the thin wall geometry with respect to the process parameters and build orientations. In some cases, the parameters may be easy to control during a build (for example, laser power and scan speed) while others must be treated as “noise factors” that are uncontrollable (for example, build orientation of a thin wall within the final heat exchanger). In the latter case, pick settings that minimize variability to reduce risk as much as possible.

This study gave the team the knowledge necessary to develop a design guideline to make thin walls that are fully dense and robust to different build orientations. In the example by Dunbar, et al., varying process parameters, along with the design geometry and build orientations, enabled them to achieve a 70% thinner wall with no porosity using custom settings when compared to standard processing parameters. Not a bad outcome for a cost-effective, rapid and intelligent prototyping study. What would you do differently if armed with such an approach?

Related Content

PowderCleanse Concept Delivers In Situ Powder Analysis for Metal 3D Printing

A collaborative project developed a prototype solution for measuring particle size distribution on the production floor, as part of the sieving step typical to additive manufacturing processes using metal powders.

Read MoreIndyCar's 3D Printed Top Frame Increases Driver Safety

The IndyCar titanium top frame is a safety device standard to all the series' cars. The 3D printed titanium component holds the aeroscreen and protects drivers on the track.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing's Evolving Role at Fathom Now Emphasizing Bridge Production

Bridge production is currently the biggest opportunity for additive manufacturing, says Fathom Manufacturing co-founder Rich Stump. How this service provider leverages AM while finding balance with other production capabilities.

Read MoreComplete Speaker Lineup Announced for the 3D Printing Workshop at NPE2024: The Plastics Show

Presentations will cover 3D printing for mold tooling, material innovation, product development, bridge production and full-scale, high-volume additive manufacturing.

Read MoreRead Next

Profilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MoreCrushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read More