Guide for Health Care Providers: How to Find (and Talk to) 3D Printing Professionals

If you are a medical professional in the U.S., you've likely heard that 3D printing can be an answer to equipment shortages. Here's how to find local 3D printing specialists and how to talk to them once you have.

Are you a hospital using 3D printed PPE? If you can spare a few minutes to talk about your experience, we’d like to hear from you: Email us.

There’s been a whirlwind of reports about how 3D printing could be a solution for manufacturing health care items in high demand because of coronavirus. 3D printing hobbyists and professionals alike are offering their skills and resources to hospitals in this time of crisis, recognizing the need that 3D printing can potentially fill. We’ve even published a map showing locations of professional service bureaus in the U.S.—while its original purpose was to help OEMs and other companies fill supply chain gaps with 3D printed parts and tooling, this could also be a resource for hospitals, clinics and other health care providers who need critical items to care for patients.

Welcome! You’ve unlocked premium content.

But if you are a medical professional, how do you use this information?

So, regular readers of Additive Manufacturing, sit tight for a moment. This post isn’t really for you. It’s for hospitals, clinics and other health care providers looking for help in this moment in time (but I hope it proves useful beyond this pandemic — maybe the questions under the “What to Expect” heading will be useful to share with new customers).

Professional service bureaus can help fill medical equipment shortages by 3D printing needed parts, broken components, tools and more. Here’s how to find one near you, and how to prepare for the conversation. Pictured: Forecast3D | Photo: HP

First, Adjust Your Expectations

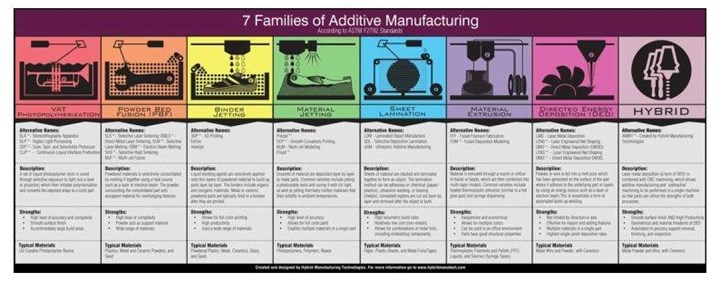

3D printing describes more than just one method of manufacturing. The desktop 3D printers now ubiquitous in schools and libraries use a process called material extrusion — plastic filament is heated, squeezed out through a nozzle and deposited on a plate layer by layer to build up a part. But this is just one kind of 3D printing. In fact, there are seven different categories of 3D printing technologies. There are other plastic printers that use powder or liquid resin; likewise there are machines that print with metal powder or wire, and some that can print with composites or layer multiple materials on top of each other. 3D printing companies might specialize in one technology or material, or they may work with a broad range.

I’m starting with this to say that 3D printing can probably do more than you think, but its strengths may not be what you expect. 3D printing is a good choice for replacement parts, small batches, rapid development of new items, and situations where a tool (like an injection mold) will be too costly or time-consuming to source. It can build complex geometries that might not be possible with other methods, and potentially offers other benefits — like the ability to combine multiple parts into one or to produce a lighter end product using less material.

While 3D printing has many advantages, though, it is not the best or even a good solution for all parts. Many of the 3D printing specialists I’ve spoken with recently have been inundated with questions about personal protective equipment (PPE) like respirator masks and gloves, and are doing their best to articulate why these items may not be a good fit for 3D printing. For one, 3D printing is not generally the fastest or cheapest solution for making mass quantities of a given part, especially one that could be easily and quickly produced with a more conventional process.

3D printers that extrude filament with a fused filament fabrication (FFF) or fused deposition modeling (FDM) process produce parts with layer lines — which may or may not be acceptable for a given application.

Or, 3D printing could introduce other limitations given the application. Early in the crisis, for instance, 3D printed respirator masks had a moment. The thinking was that a flexible or rigid plastic mask with a filter can be sterilized and reused more easily than a conventional N95 mask. Without even getting into considerations like fit, sensitization and appropriate materials, a major hurdle was that most of the mask designs circulating the internet were intended to be made with extrusion-style 3D printers — but this process invariably leaves layer lines in the part. Without postprocessing to remove them (which adds time and complexity to manufacturing), such a mask would be left with small crevices where microbes could potentially gather, making it difficult or even impossible to fully clean between uses.

(While no 3D printed N95 equivalent has been accepted by the FDA yet, there are currently designs for surgical and first responder masks made with selective laser sintering [SLS] technology, as well as extrusion-based designs that function as frames for filter materials and which pose fewer risks. For more on masks, see the FDA’s FAQ regarding 3D printed PPE and medical devices.)

So, what kinds of items are good candidates for 3D printing? Replacement parts for legacy or broken equipment. Components to improve existing systems — ventilator parts potentially fall into this category, as a result of the FDA relaxing certain restrictions to allow for easier changes to existing products. Visors for face shields. Non-medical items such as hands-free door openers. Note that these are just a few examples; for specific needs, it’s best to check with your local service bureau about their expertise and capabilities, which leads to this next section:

How to Find a 3D Printing Professional

Note: professional. There are many hobbyists, students and others offering their skills right now — it’s a noble cause, and there are certainly applications that can be produced with a home 3D printer with little to no steps needed outside of the actual printing.

A company offering reverse engineering services may have laser scanning technology (pictured) and other tools to recreate a needed part. Photo: Exact Metrology

But, a professional service bureau is going to be better equipped to deal with, say, a broken valve in a ventilator. An industrial 3D printing firm is likely to have reverse engineering capabilities like 3D scanning and CAD expertise to recreate a needed part. They may have experience making similar components in the past, as well as running a range of different materials. These service providers will be able to help with parts that require finishing like polishing or cleaning (and just about any part that needs to be sterilized will likely require finishing). They can help inspect parts and ensure quality. A service bureau that focuses on medical items should be FDA registered (a requirement for 3D printing of swabs, for example) and may even have cleanroom facilities, sterilization and packaging capabilities. If the need is for a medical device subject to FDA approval, a professional service bureau is going to be much better positioned to deal with that qualification process.

Where do you find 3D printing professionals? Organizations like America Makes* and regional manufacturing or business associations often maintain lists of members and capabilities. For a quick visualization of 3D printing service providers nearby, though, take a look at our Google Map which is being updated daily with new information.

*3/30/2020 update: America Makes has launched a matchmaking service to connect health care providers with appropriate additive manufacturing capability. If you’d like assistance in finding providers, input a request here.

Once you’ve located some options, you may want to check the company’s website for more information. If the item you need requires FDA oversight, it’s a good idea to look for a supplier that is ISO 13485 certified. If it’s a broken component, you may need a supplier with reverse engineering capabilities like 3D scanning capability. Don’t rule out a supplier based on materials, however; we’ve seen a number of success stories where a plastic part could replace a metal one, for instance, and many service bureaus have relationships with machine shops and other partners who can help source something they may not be able to make in house. It’s best to reach out and talk to your local service bureau(s) to find out what they’re capable of.

What to Expect When Approaching a 3D Printing Service Bureau

When you do begin a conversation, there are a handful of questions 3D printing professionals are likely to ask in order to determine if and how they can help. Ginger Ruddy, Cimquest senior account executive and Women in 3D Printing ambassador, shared these application-qualifying questions with me:

- What is the item’s intended purpose? Understanding the part’s function is the first step in thinking through its design, materials and other considerations. Parts like ventilator components and medical devices in contact with skin or bodily fluids will have much stricter requirements than non-medical items. Something like a respirator mask would need to be made with a biocompatible material, cleaned thoroughly to remove any particulate that could be breathed in, and then postprocessed to ensure a smooth surface that can be sanitized.

- What are the anticipated volumes? Knowing how many items are needed helps a 3D printing expert decide between types of technologies or printers that may be available. If very large quantities are needed or the item could be more easily made with another process, he/she might recommend a solution other than 3D printing like injection molding or vacuum forming, perhaps with a 3D printed tool.

- What are the critical features and surfaces? Most 3D printing processes will build parts that have initial surface roughness. If any of the surfaces needs to be smooth, it will need finishing — like machining, polishing or coating — which will add to the time and complexity to the manufacturing process.

- Are there any tolerance or accuracy requirements? A ventilator component that has to create suction, for instance, has tighter tolerance requirements than a face shield visor. Again, understanding the function of the part will help to answer this question.

- Are there any environmental conditions to be considered? If yes, those conditions will shape material choice and other engineering decisions. Some questions to consider: Will this part be exposed to chemicals or liquids? Loads, torques, PSI or temperatures? Will it have sustained or cyclical skin contact or bodily fluid contact?

- Are you open to design changes? A part designed to be machined, formed or injection molded may not be a good fit for 3D printing as-is. A service provider may suggest changing the design to ensure that the part can be printed successfully and postprocessed easily. Sometimes design changes bring additional benefits; printing might mean that less material can be used, making an item lighter, or could make it possible to print a an assembly of parts as just one piece. Keep in mind that redesigning will add engineering time to the project.

- Are there any special regulatory requirements? Although the FDA is loosening requirements for medical devices in some cases as a result of the COVID-19 situation, any similar changes or parts will still need its approval. A service bureau who has worked with the FDA before is going to be better prepared to work out emergency alternatives like ventilator splitters. Note that “FDA approval” describes devices that have received this designation for a specified manufacturing process, not the material or machine alone. Simply using a biocompatible material is not enough.

- Is there a price point to hit? We are living through unusual circumstances, and I have spoken with many 3D printing service bureaus who would like to help by volunteering their time, resources and expertise in making necessary health care items. That said, not every needed item would meet these conditions and not every business can afford to help in this way. If there is a cost for the needed item, it is best to be up front about the realistic price point to help the service bureau decide whether and how to produce it.

Related Content

Video: 5" Diameter Navy Artillery Rounds Made Through Robot Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Instead of Forging

Big Metal Additive conceives additive manufacturing production factory making hundreds of Navy projectile housings per day.

Read MoreActivArmor Casts and Splints Are Shifting to Point-of-Care 3D Printing

ActivArmor offers individualized, 3D printed casts and splints for various diagnoses. The company is in the process of shifting to point-of-care printing and aims to promote positive healing outcomes and improved hygienics with customized support devices.

Read MoreMachine Tool Drawbar Made With Additive Manufacturing Saves DMG MORI 90% Lead Time and 67% CO2 Emission

A new production process for the multimetal drawbar replaces an outsourced plating step with directed energy deposition, performing this DED along with roughing, finishing and grinding on a single machine.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreRead Next

3D Printed Device Allows Multiple Patients on One Ventilator

Emergency authorization from FDA allows for use of device permitting four patients to use a shared ventilator. HP involved in mass production via additive manufacturing.

Read More3D Printing Fills Gap for Biocompatible Materials

With the Arburg Freeformer, the Aesculap division of medical company B. Braun has recently ramped up its high-volume AM production activities. This is because, particularly in medical technology, the main focus is on options such as the processing of biocompatible materials.

Read MoreStratasys Ramps up Production of 3D-Printed Personal Protection Equipment for COVID-19

Stratasys Ltd. has announced a global mobilization of the company’s 3D printing resources and expertise to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The initial focus is on providing thousands of disposable face shields for use by medical personnel.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)

.JPG;maxWidth=150;quality=70)

.JPG;maxWidth=400;quality=70)