Can Microscale 3D Printing Reduce Surgeries for Glaucoma Sufferers?

Boston Micro Fabrication (BMF) is exploring this promise. Eye stents are made of metal today. Fine-detail additive manufacturing can enable polymer instead, improving patient experience.

Additive manufacturing (AM) sometimes offers a simpler approach to production compared to conventional manufacturing, but just as often, AM is chosen because it permits a design advantage other processes cannot achieve. Eye stents used in glaucoma surgery might be an application that achieves both. Microscale 3D printing promises to simplify how these eye stents are made, while also improving the experience for the patient by reducing the number of glaucoma surgeries from two to only one.

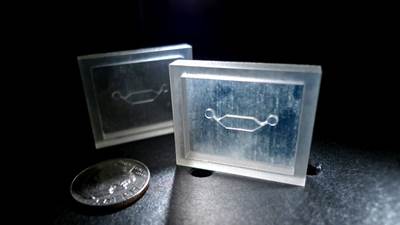

The 3D printed eye stent for glaucoma surgery is about 1 mm long. Photo courtesy BMF.

All this is still speculative. 3D printing technology provider Boston Micro Fabrication (BMF) has been working with a maker of eye stents to explore and validate the possibility. But BMF CEO John Kawola recently described to me the promise of this application.

Glaucoma stents today are tiny precision implants about the size of an eyelash produced through microscale CNC machining of titanium. The purpose of the stent is to provide small channels in the patient’s eye that can drain fluid to reduce pressure. Micromachining these fine parts is a challenging operation relatively few manufacturers are equipped to do, Kawola notes.

BMF sees an opportunity because the company’s focus is 3D printing technology for microscale work. It has developed a microscale 3D printing platform employing digital light processing (DLP), or curing resin to produce solid parts, a technique others have proven for production. BMF adds to this process precision optics and a machine bed with precise X-Y movements, all to enable 3D printing to an X-Y resolution of 2 microns. The result is much easier microscale production. Micromolding and micromachining are both more difficult than their macro-scale equivalents. But 3D printing a tiny part on BMF’s machines can be just as straightforward as 3D printing a larger part.

Parts that require “holes down to 20 or 30 microns in diameter, or walls down to 30 or 40 microns in thickness” represent “a portion of the market we feel has not been served well by 3D printing in the past,” Kawola says. Implants such as eye stents for glaucoma surgery are part of this portion of the market, as are tiny electrical connectors and microfluidic components. Indeed, the 3D printed eye stents under evaluation are smaller than eye stents used today.

But rather than the chance to make the tiny part easily, arguably it is the chance for a material change that brings the most striking advantage to the stents for glaucoma surgery. Machining in metal is the only practical way to produce the stents today with the necessary fine precision and to the relatively low quantities needed. Microscale 3D printing on the BMF platform opens the way to making the parts from polymer instead. The stents can therefore be made to dissolve in the body. Today, glaucoma sufferers need one surgery to implant the metal stent, another to remove it. In the future, the second surgery might be eliminated.

Micro 3D Printing for Tiny Connectors: The Cool Parts Show S3E4

Microscale AM offers an alternative to micromolding and micromachining. On this episode of The Cool Parts Show, 3D printed electrical connectors are our smallest cool part yet. WATCH

Related Content

Possibilities From Electroplating 3D Printed Plastic Parts

Adding layers of nickel or copper to 3D printed polymer can impart desired properties such as electrical conductivity, EMI shielding, abrasion resistance and improved strength — approaching and even exceeding 3D printed metal, according to RePliForm.

Read More3D Printed Spine Implants Made From PEEK Now in Production

Medical device manufacturer Curiteva is producing two families of spinal implants using a proprietary process for 3D printing porous polyether ether ketone (PEEK).

Read More3D Printed Lattices Replace Foam for Customized Helmet Padding: The Cool Parts Show #62

“Digital materials” resulting from engineered flexible polymer structures made through additive manufacturing are tunable to the application and can be tailored to the head of the wearer.

Read More3D Printing with Plastic Pellets – What You Need to Know

A few 3D printers today are capable of working directly with resin pellets for feedstock. That brings extreme flexibility in material options, but also requires greater knowledge of how to best process any given resin. Here’s how FGF machine maker JuggerBot 3D addresses both the printing technology and the process know-how.

Read MoreRead Next

Where 3D Printing Makes Sense for Micro Medical Devices

A contract manufacturer uses stereolithography to produce high-quality medical devices on a micro-scale for prototyping and end use.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More