It was a situation that might be described as an OEM’s worst nightmare. The manufacturing line churning out agricultural equipment suddenly had to be stopped. The line was down, and it was unclear when it would resume production.

The problem wasn’t with the manufacturing equipment or even a piece of the engine itself, but with a plastic cap used for masking part of the engine during painting. While a simple piece of tooling, the cap was a nonstandard size and had become unavailable. To continue making engines, the manufacturer would need to find an alternative for this small but necessary part — and for that, it turned to Würth Group, a global distributor of products ranging from personal protective equipment (PPE) to industrial equipment to fasteners.

Most of the items that Würth provides are conventionally manufactured, but at the time that the missing masking caps interrupted engine production, the company was in the midst of experimenting with 3D printing for smaller runs of more specialized parts. Rather than reverse-engineer a tool and injection mold replacement caps, Würth applied its internal 3D printing capacity to make the caps more quickly and get the line running again. The customer received the printed caps for about $20 each — not necessarily a cheap alternative, but certainly far less expensive than stopping engine production entirely.

Würth’s successful delivery of these 3D printed plastic caps in record time served as a catalyst for the creation of a new business unit, Würth Additive Group. Like its parent company, this group is also a distributor, supplying a number of industrial 3D printers alongside materials, postprocessing machines and safety equipment. But it is also doing something even more transformative. Building on that early success, a major part of this group’s activity is developing 3D printed part programs in pursuit of the ultimate promise: digital inventory.

The SKU That Can Become Anything

To be clear, Würth is not interested in becoming a contract manufacturer or supplying tens of thousands of 3D printed parts to its customers. Instead, the company sees additive manufacturing as the natural extension of the activities it is already good at: sourcing and distributing parts as they are needed.

Inventory for the Würth Group currently looks like this: physical parts held in large warehouses. The company is now developing parts for digital inventory which can be made as needed, by Würth, at a service bureau or internally by the client.

Today most of these components are sourced in bulk from affiliate manufacturers and stored in one of the company’s warehouses around the world. But mass production and mass storage don’t make sense for many parts that might be spares, replacements or specialty items only needed in low quantities.

For these parts, Würth Additive Group is now building out digital inventory programs — in other words, creating repeatable additive manufacturing workflows so that these items can be produced on demand at a moment’s notice, either by Würth, a service bureau or the customer itself. It’s a different way of thinking about inventory and supply, says AJ Strandquist, CEO of the Würth Additive Group.

“Instead of parts, you can have filament and resin be the inventory,” Strandquist says. “The material can be just one SKU coming in that can become many other things.”

Many OEMs no longer want to single-source their products and have little interest in closed ecosystems post-covid, Strandquist says. Additive manufacturing brings flexibility and redundancy not possible with machining, injection molding or other conventional processes reliant on hard tooling, even when working with a single partner to source it. A part that lives in digital inventory rather than a physical warehouse is replicable when and where needed, provided that its digital record is complete enough to enable this.

Managing Liability in Digital Inventory

We’ve reached a point, Strandquist believes, where truly digital inventory enabled by additive manufacturing is possible. 3D printing technology has advanced to the point that the equipment and process are no longer the hurdles to adoption.

Now, “It’s documentation,” he says. “It’s paperwork. Liability is 90% of decision-making, and it needs to be adequately addressed.”

Case in point: The automotive repair industry could benefit tremendously from implementing 3D printed replacement parts for damaged cars. But it largely hasn’t, because there are no benchmarking or validation standards for these parts. A collision repair shop using a 3D printed replacement without these guardrails would be at risk.

“Right now, they’d be using a part no one agreed to,” Strandquist says. “If it fails, who is at fault?”

“It is not enough to create a digital supply chain,” points out technology leader Mikhail Gladkikh. “How do you manage it? How do you connect all the pieces?”

Answering these questions, Gladkikh says, is within Würth’s DNA as a longstanding parts supplier with procedures and digital solutions to manage conventionally sourced parts. The logistics, in other words, are already in place for these parts, and with prep work, 3D printed parts can be plugged in too.

Würth partners with AM technology providers and customers to establish production part approval processes (PPAPs) that ensure consistency and confidence in digital inventory parts. The work is case-by-case and the development has to go deep, but the payoff is a digitized part that can be produced on demand and repeatably every time, and sourced within Würth;s existing systems like any other.

“AM fits well into the existing digital supply chain,” Gladkikh says, “because we can certify 3D printed parts the same as any other part we make.”

In many cases, this means that 3D printed parts can be sourced through Würth channels without significantly changing the customer experience. Clients can continue to work with their same Würth account manager, even if parts are provided through the Additive Group. But the ultimate promise for the digital supply chain might be for clients to take on the production of their own digital inventory through 3D printing, and the group is working to enable this as well.

Welcome to the Hangar

I met with Strandquist, Gladkikh and other members of the team including Ed Tackett, additive manufacturing lead technologist, and Jacob Ayers, lead technician, at Würth Additive Group’s recently established facility in Greenwood, Indiana. The company’s additive efforts began at a nearby Würth warehouse, but when the Group outgrew the available space, it relocated to a repurposed airplane hangar at the local airport.

Most of the work of developing digital inventory programs with AM is now happening at this new space, which has been decked out with multiple 3D printers and other technologies, plus classroom space and a series of shipping containers stacked like Jenga blocks that serve as climate-controlled offices.

But despite a selection of polymer and metal 3D printers on site, the hangar is not meant to be a production facility. Instead its purpose is threefold: to be a lab for developing programs that will be carried out by customers internally; a classroom for training those customers; and a showroom for the 3D printers and auxiliary equipment the company now supplies, some of which is pictured below.

3D Printing Equipment at Würth Additive Group

But aside from a technology stack, Würth Additive customers who are pursuing digital inventory applications also receive a fully developed process for manufacturing their particular product with the equipment they purchase. The company can do most of the heavy lifting for customers, from calculating costs and equipment needs through developing parts for the digital inventory, handing over a nearly turnkey process for their digital inventory parts at the end.

“We can save them five years of development,” Ayers says.

Clients receive a fully developed end-to-end process that accounts for 3D printing as well as all the steps around it. For example, as a solution for parts smaller than the Kurtz Ersa’s build plate, Würth might recommend printing onto smaller inset build plates so that parts can easily be lifted out when complete and production can continue. (Another example of a similar build plate strategy.)

3D Printing for Automotive Repair Parts

Most of Würth Additive Group’s process development work at present is focused on assisting OEMs in the industrial equipment and automotive sectors. Getting back to the challenge faced by auto collision shops, Würth sees significant value in applying 3D printing for items like autobody clips. These small plastic fasteners are typically made through injection molding. Compared to 3D printing, molding results in a lower cost per clip, but this is the wrong way of thinking about these parts and others like them, Tackett says. The cost calculation needs to take into account the price of not having a necessary part when it is needed.

“Each of these clips might cost only 50 cents to source through injection molding,” he says, “but if they aren’t available and dealerships have to wait to complete a repair, suddenly that clip might cost 6 weeks of a rental car while the vehicle sits in the shop.”

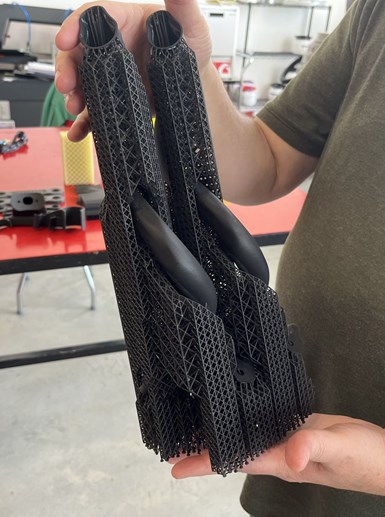

These autobody clips are conventionally produced by a Würth affiliate company. They can be reproduced with DLP without significant design changes, but modifications like the sacrificial hex grid make them easier to process. Thirty parts in this structure can be treated as one until it is time to separate them.

If instead that clip existed in a digital inventory, as a ready-to-go, pre-certified OEM part, the dealership could quickly source it from a local 3D printing facility or perhaps even print it on site. Würth is exploring possibilities like this for the broader automotive industry. As announced during the International Bodyshop Industry Symposium (IBIS) in April 2023, the Additive Group is bringing its expertise as a distributor to help roll out solutions like this as part of the 3D Printing in Auto Collision Task Force (led by Ford Motor Company alum Harold Sears) working to make AM part of the automotive repair supply chain.

Würth is probably best known as a provider of fasteners, but the parts it is preparing for the digital inventory can be larger components like these air ducts. “We make all the unaesthetic parts — wire harnesses, applicators, air tubes,” quips Ayers.

But in the meantime, the Additive Group is working on digital inventory alternatives for parts where it already has access as a supplier or distributor. The clip pictured in this article is a real example of an autobody clip, in this case made by a Würth affiliate company. Würth Additive Group now manufactures small batches of these clips using its DLP 3D printers, sticking closely to the original injection molding design.

“If the customer needs a clip, they could care less how it’s made,” Tackett says, and in many cases 3D printed parts need to coexist and be exchangeable for their conventional counterparts. A 3D printed clip might end up in the same bin as molded specimens. That’s why “95% of the parts we work on require no DFAM,” he says. Providing a workable replacement takes precedent over implementing design optimizations or other major changes.

The minor design tweaks made to the clips have therefore focused primarily on changes to support printability, such as adding venting and optimizing break points. Parts were also grouped together in a sacrificial hex grid for easier processing. The entire batch can be treated as a “part kit” that stays together for printing, cleaning and curing. The strategy saves time and reduces touches on all the parts, as well as eases traceability.

“You can deal with 30 parts as if they are one part,” Ayers says, illustrating the kind of process-level thinking that Würth is bringing to digital inventory implementation efforts.

3D Printing to Deliver the Critical Widgets

There is still a long way to go to make automotive body clips or other fasteners, brackets and industrial components fully digital parts on a large scale. But for every component that Würth Additive Group can develop for the digital inventory, it potentially saves time, money and headaches down the road. As the autobody clip above illustrates, this transition can be accomplished with minimal disruption to the customer and end user, and more importantly, improve their experiences by ensuring that these items are readily available.

“Our approach is integrated with the way they do business right now,” Tackett says. Würth can continue to play the role of parts provider and distributor, even as more and more of these parts become digital files rather than physical inventory.

“A $1 million machine makes so many things unaffordable,” Strandquist says, which is why so many additive parts seem to be high-value, complex components. Würth instead sees the value in adopting more affordable equipment to pursue digital inventory of mundane but necessary parts.

“It’s a new way to make parts, but OEMs can still make products by plugging into the same universe of suppliers,” Gladkikh says.

More than this, OEMs can still derive value and make money from spare and replacement parts; the difference is that they no longer also need to carry the cost of maintaining a stock of these components at all times. As Würth is finding, there is plenty of value to be gleaned from digitizing the manufacture of parts like clips, brackets, caps and other parts that may be easy to overlook, but might be the key to getting a car back on the road or an assembly line back up and running.

“You don’t need to be making rocket parts to make additive manufacturing work,” Strandquist says. “We are filling the gap for obsolete and warranty parts — the places where you need that widget, no matter what.”

Related Content

8 Transformations 3D Printing Is Making Possible

Additive manufacturing changes every space it touches; progress can be tracked by looking for moments of transformation. Here are 8 places where 3D printing is enabling transformative change.

Read MoreSeurat: Speed Is How AM Competes Against Machining, Casting, Forging

“We don’t ask for DFAM first,” says CEO. A new Boston-area additive manufacturing factory will deliver high-volume metal part production at unit costs beating conventional processes.

Read MoreThis 3D Printed Part Makes IndyCar Racing Safer: The Cool Parts Show #67

The top frame is a newer addition to Indycar vehicles, but one that has dramatically improved the safety of the sport. We look at the original component and its next generation in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreA Tour of The Stratasys Direct Manufacturing Facility

The company's Belton manufacturing site in Texas is growing to support its various 3D printing applications for mass production in industries such as automotive and aerospace.

Read MoreRead Next

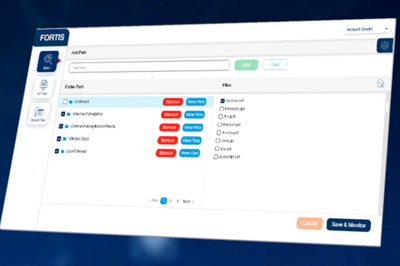

Platform Backed by Blockchain Provides Data Assurance for Additive Manufacturing

VeriTX’s Fortis platform offers “data assurance as a service” to protect digital information from tampering. The product is launching with an initial focus on files intended for 3D printing.

Read MoreWürth CEO Joins 3D Printing in Auto Collision Task Force

The task force will evaluate how 3D printed auto parts can be used to assist in the collision and automotive repair sector in a safe and regulated environment.

Read MoreIs a Functional 3D Printer Network Possible? Automation Alley’s Project DIAMOnD and the Industry 4.0 Future

The initiative that placed 3D printers at more than 300 Michigan manufacturers is laying the groundwork for a future in manufacturing that is digital, distributed and largely additive.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)