Penn State to Install Super-Finishing Lab for Metal 3D-Printed Parts

The funding for the lab is part of a one-year project to explore the uses of metal 3D printing for naval applications.

Penn State researchers have received more than $535,000 to install a state-of-the-art “super-finishing lab” for 3D-printed metal parts as part of a project to explore the use of 3D printing in naval applications. The new lab will complement the existing subtractive processing technology in the Factory for Advanced Manufacturing Education (FAME) Lab within the Harold and Inge Marcus Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering.

Together the machinery will provide the subtractive processing capability necessary to transform printed parts into components ready for product assembly. The equipment in the FAME Lab, which is physically located in the Leonhard Building on West Campus, will be used for both the instruction of engineering students as well as academic research.

Funding for the one-year project, titled “Super Finishing of Printed Metallic Parts for High Performance Naval Systems,” is being provided by the Defense University Research Instrumentation Program, which operates through the Department of Defense’s Office of Naval Research. Ed DeMeter, a professor in the Marcus department, is the principal investigator on the project.

“The Navy has a strong interest in identifying and researching the technical issues of using 3D-printed metal parts for naval applications now and in the future,” De Meter says. “They want to better understand how to design parts while identifying potential barriers and also benefits that may arise between the metal printing process and any secondary processing that is done to smooth out the surface texture of these parts.”

Metal parts can be printed to near-net shape, but require thermal processing to improve their material properties and hard tool machining processes to remove supports and create functional surfaces, according to De Meter.

“Super-finishing processes are used to remove burrs and to smooth surfaces. All three post processes are needed to produce parts for demanding national defense applications, which include jet engines and sea vessels,” he said.

Functional surfaces of the parts need to have extremely tight geometric control and a very smooth surface finish, explains DeMeter. If a part is subjected to a lot of cyclic loading (i.e. force, vibration, etc.), and has rough surfaces, it promotes the formation of cracks and premature failure of the parts.

“In parts like those the Navy uses, there are a number of internal passageways involved,” he says. “If the part is printed and the finish of the passageway is rough, it’s going to interfere with the flow; or if there are loose particles from the printing process in any crevice of the part, and they break free during the application, it can cause not only the part to fail but the entire system to fail.”

Joining De Meter on the research team are Rich Martukaniz, director of Penn State’s Center for Innovative Materials Processing through Direct Digital Deposition (CIMP-3D) and head of the Laser Processing Division in the Applied Research Laboratory; Saurabh Basu, assistant professor of industrial and manufacturing engineering; Guha Monogharan, assistant professor of mechanical engineering; Hojong Kim, assistant professor of material science and engineering; Todd Palmer, professor of material sciences and engineering and engineering science and mechanics; Edward Reutzel, associate research professor with the Applied Research Lab; Tim Simpson, Paul Morrow Professor in Engineering Design and Manufacturing; Jingjing Li, William and Wendy Korb Early Career Professor in the Marcus department; and Robert Voigt, professor of industrial and manufacturing engineering.

De Meter said the group’s focus of the initial research proposal was threefold. First and foremost, it is to establish expertise on how parts made using additive manufacturing (AM) processes will react when they are super finished and installed in complex assemblies. That general processing knowledge could then be shared via best practices to the overall community because, according to De Meter, such public information does not currently exist.

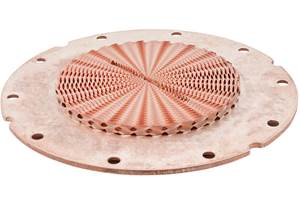

Secondly, the team wants to look into the finishing of metal parts that feature tight lattice structures to find out if the processes are able to polish some of the intricate passageways of the parts.

“If we find out there are deficiencies in finishing these parts, which we suspect there will be, that’s where we will want to work on process development,” says De Meter.

The third component of interest for the researchers is education. The vision of the team is to create graduate-level courses that could be offered online to employees of those companies who use the finishing processes on 3D-printed metal parts.

“It’s more convenient and economical for these employees to take some courses online than it would be for a company to pick up the cost of sending them off-site to learn about these technologies,” says De Meter.

Related Content

VulcanForms Is Forging a New Model for Large-Scale Production (and It's More Than 3D Printing)

The MIT spinout leverages proprietary high-power laser powder bed fusion alongside machining in the context of digitized, cost-effective and “maniacally focused” production.

Read MoreDMG MORI: Build Plate “Pucks” Cut Postprocessing Time by 80%

For spinal implants and other small 3D printed parts made through laser powder bed fusion, separate clampable units resting within the build plate provide for easy transfer to a CNC lathe.

Read More3D Printing Molds With Metal Paste: The Mantle Process Explained (Video)

Metal paste is the starting point for a process using 3D printing, CNC shaping and sintering to deliver precise H13 or P20 steel tooling for plastics injection molding. Peter Zelinski talks through the steps of the process in this video filmed with Mantle equipment.

Read MoreWith Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM), Cooling Technology Is Advancing by Degrees

San Diego-based Fabric8Labs is applying electroplating chemistries and DLP-style machines to 3D print cold plates for the semiconductor industry in pure copper. These complex geometries combined with the rise of liquid cooling systems promise significant improvements for thermal management.

Read MoreRead Next

Crushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read MorePostprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More