Learning Curve

A manufacturer that has succeeded for three generations expects additive manufacturing to be part of the reason why it will succeed in the fourth. One year into its investment in the technology, here is the company’s experience so far.

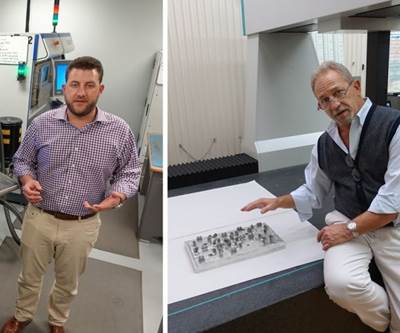

Christian M. Joest, owner and President of Imperial Machine & Tool Co., had no delusions about additive manufacturing. Last year, the New Jersey contract manufacturing company bought its first additive manufacturing machine for production metal parts: a selective laser melting system from SLM Solutions. Even as he was committing to the purchase, Joest was telling employees, “We will probably lose our shirts on this machine for a while.”

That’s OK. Thanks in part to a variety of long-term customer relationships, Imperial has the strength and the stability to wait out, and even confront, what Joest sees as the big problems still facing additive manufacturing today. One of those problems is that the technology is immature. In the future, he expects the equipment for making parts through additive layers to be faster, cheaper, more repeatable and more capable than it is today. He also expects its application to be much better understood. The resulting difference could be as great as the difference between early portable phones and the smartphones of today. “All of us currently doing additive manufacturing might be using the bag phone version of this technology,” he says.

The other problem is that the market is immature. The demand for production metal parts made through additive manufacturing is still so small as to be effectively zero, he says. The manufacturer therefore has to create the demand instead. That is, the manufacturer has to obtain the additive production capability first, then set about educating potential customers about the ways they can benefit from the capability.

This is precisely the course Imperial has taken. Despite the problems, Joest says the reason for taking this course now is because additive manufacturing is the future. He has little doubt. The two problems described above are temporary and small compared to the promise additive manufacturing offers to save cost and improve the designs of manufactured products. Joest wants Imperial to help its customers start realizing the benefits of additive manufacturing today, in part because this third-generation business owner fully expects Imperial to continue to advance and succeed under the fourth-generation leadership of his son, Christian G. Joest. Getting there—remaining in a position to answer customers’ most pressing manufacturing needs—will mean mastering additive manufacturing.

In this, Imperial does have a leg up. The company leader says some of the attributes distinct to his particular manufacturing business position it well for moving ahead with additive technology. Not the least of those advantages is the emphasis on long-term relationships.

Long View

The move toward seeking and serving regular, established, long-term customers is perhaps the most significant change that Imperial’s current president has made to the company during the tenure of his leadership. The goal Joest has followed for years is to make Imperial the go-to manufacturing resource for key customers that will return again and again. Today, the manufacturer gets just about all of its business from 15 companies and defense-related government entities. It routinely turns down short-term work that does not promise to turn into lasting business, because the short-term work would distract it from serving the long-term customers.

This model is valuable for additive manufacturing because of the inside knowledge that comes from these relationships. Over time, the extent of Imperial’s interaction with these returning customers has given the company a depth of understanding about these organizations’ needs and challenges that few manufacturing contractors possess. Those needs and challenges provide the opportunity. Additive manufacturing is probably not a replacement for processes that are working well today, but it likely does offer the answer to many of the challenges that current processes can’t address.

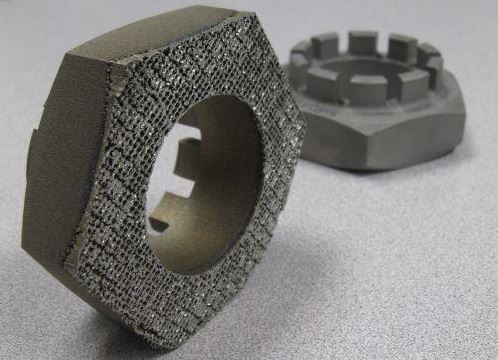

A recent example involved a well-known piece of military artillery, the M777 howitzer. Military engineers regularly seek to make improvements to the design of this gun that increase its weight. However, the weight of this gun is constrained—it has to be light enough to be underslung and carried by aircraft. Therefore, before any hoped-for improvement can be made, weight savings have to be found elsewhere on the gun. Through additive manufacturing, Imperial was able to deliver a new option for weight savings. On its SLM machine, the company grew large fastening nuts for the gun’s assembly that were not solid like the existing nuts, but instead had a honeycomb structure inside. The new nuts were just as strong as the old ones, but half the weight. The combined weight savings from all of the M777 nuts produced this way gave the military engineers freedom to add new components.

That military connection is another advantage relevant to additive manufacturing, says Joest. Granted, it is not a sweeping advantage, because the military makes manufacturing changes slowly. However, he says spare parts for military hardware represent an area in which additive manufacturing could deliver considerable value. The ability to “print” these spare parts as needed, instead of requiring depots to store either shelves full of finished parts or shelves full of bar and billet stock for machining them, promises dramatic savings. The chance to also redesign some of these parts for improved performance, as in the case of the howitzer nuts, makes the case even more compelling.

One other attribute of the company that favors additive manufacturing is this: Imperial’s machining area is already committed to lights-out production. The shop is staffed only by day, routinely leaving CNC machine tools to continue running through the night. For example, a common practice in this shop is to fixture a vertical machining center for the daytime project only on the right side of the machine’s table, because fixturing is kept in place on the left side of the table that will allow the machine to run a batch of production parts through the night. This culture of running unattended makes additive manufacturing a natural fit, because with cycles times of 20 hours or more for even a moderate-size part, additive manufacturing is inherently a lights-out process.

Learn By Doing

Since the SLM machine arrived last year, the Imperial employee who has been the most directly involved in getting to know its capabilities is Design Manager John Shelp. He says the learning curve with this or any metal additive manufacturing system can be characterized in one word: parameters. The company initially had no idea how to work with adjustable parameters including laser speed, laser heat and dwell time to account for the challenges of different part features and the behaviors of different materials in the additive process. It knows much more today, but Shelp says there was no way to achieve this understanding except through considerable trial and error.

Fortunately, Shelp is patient, and the company was patient about the learning process it asked him to carry out. He says plenty of times he would return to the machine at the end of a cycle only to discover that the build had been unsuccessful and the part had collapsed—meaning the only payoff from hours of machine time was yet another opportunity to diagnose how to run the cycle better next time.

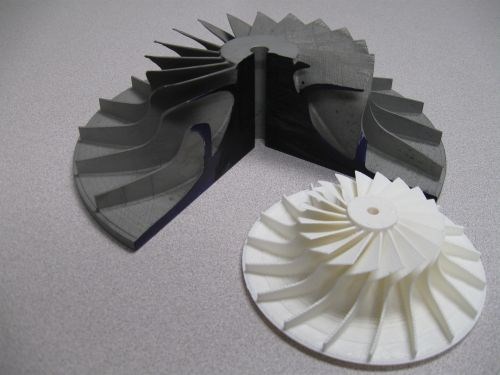

One large impeller took 4 days to build, and the first try failed to produce the part successfully. Vanes broke under their own weight during the cycle. In that case, the parameter that needed to be adjusted was the speed of the augur bringing powder to the laser. Increasing the material delivery rate allowed the cycle to generate the vanes to the solidity required.

Experiences such as this reveal why the phrase “3D printing” is something of a misnomer. In no way is additive manufacturing as easy to apply as a computer’s desktop printer, Shelp says.

Now, Imperial has ascended much of that learning curve related to process parameters, but success is throwing the company another curve. The next set of challenges—looming soon—relate to production volume.

Full Production

Though Joest predicted the company would lose money on additive manufacturing for a period of time, that period might already be near an end. Testing related to a customer’s still-secret production possibility has gone well, he says. The customer sees value in producing a certain small, high-volume component through an additive process. Joest says that if this job goes forward, then additive manufacturing would become profitable for Imperial, but the company would then be committed to producing hundreds of these small pieces at a time in one additive cycle after another.

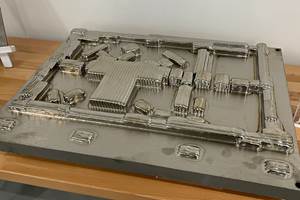

One seemingly simple issue arising from this prospect is actually a significant challenge. The SLM machine builds parts by layering them onto a build plate that serves as the anchor for the process. Once the build is complete, what is an efficient way to cut all of those hundreds of pieces off of the plate? A finely precise method is needed, but EDM probably won’t be fast enough to be practical, he says. This is yet another question for which there are no established answers, because additive production is so new. Therefore, Imperial will find the answer. Stay tuned, Joest says.

Related Content

How Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreVideo: 5" Diameter Navy Artillery Rounds Made Through Robot Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Instead of Forging

Big Metal Additive conceives additive manufacturing production factory making hundreds of Navy projectile housings per day.

Read More3D Printed NASA Thrust Chamber Assembly Combines Two Metal Processes: The Cool Parts Show #71

Laser powder bed fusion and directed energy deposition combine for an integrated multimetal rocket propulsion system that will save cost and time for NASA. The Cool Parts Show visits NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

Read More3D Printing Molds With Metal Paste: The Mantle Process Explained (Video)

Metal paste is the starting point for a process using 3D printing, CNC shaping and sintering to deliver precise H13 or P20 steel tooling for plastics injection molding. Peter Zelinski talks through the steps of the process in this video filmed with Mantle equipment.

Read MoreRead Next

Staying Focused on the Promise of AM

For this company, realizing that promise is a long-term undertaking. In the short term, it involves sometimes saying no.

Read MoreDoes Additive Manufacturing Make Sense in a “Subtractive” Machine Shop?

Definitely yes, says this shop—a metal 3D printed part is almost always a machined part as well, and an established machine shop is perhaps the best business to realize AM’s promise for production.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More