Does Manufacturing Need Additive?

If a subtractive manufacturing operation is going smoothly, AM need not replace it. So what is AM good for, and why do we need it in the first place?

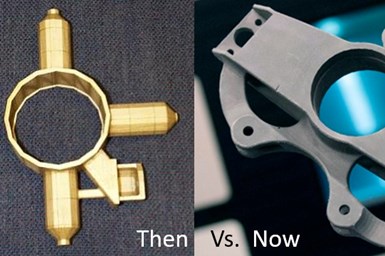

Then vs. Now: 3D printing succeeded in solving the “prototyping problem” (market pull) while AM offers more design freedom for end-use parts (technology push).

Photo Credit: Timothy W. SimpsonThis column has encouraged users to find production scenarios in which additive manufacturing makes sense and offers advantages over conventional manufacturing methods.

Thinking about these production scenarios where AM might win led me to a more interesting question: Is the goal of AM to replace conventional manufacturing methods at an enterprise level or just on a part-by-part basis? Many have argued that AM is “all or nothing” — obviously it is not — but will AM only be successful if it achieves the efficiencies and economies of scale that we associate with mass production?

I don’t think so, and we can thank Henry Ford for creating that paradigm. Instead, let’s look at it the other way around.

If conventional manufacturing is working just fine, then why use AM? If parts are being delivered on time and costs are reasonable, why change tactics? If production volumes justify the tooling investment, then why consider AM? If your supply chain is working just fine and your channels are operating efficiently, then why switch to AM? Last, but not least, if your customers like what you are selling and aren’t willing to pay for personalization or the performance benefits of a lightweight part that can only be made with AM, then is it worth the investment?

In short, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Or in this case, don’t use AM.

So why use AM in the first place? Pondering this, my mind wanders back to the origins of AM in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before iPhones and iPads, even before iMacs and iPods. Computers weren’t fast or cheap, and they certainly weren’t as ubiquitous as they are today. Graphics cards and computer monitors paled in comparison to what they are now, so designers relied mostly on 2D drawings, blueprints and sketches to share their design ideas and concepts. Computer-aided design (CAD) software had only been around a decade or so, but it was expensive, and everyone would have to huddle around a small screen to see images, still mostly in 2D. Projecting images from your computer onto a wall or giant video screen wasn’t possible. That technology was too expensive or didn’t exist yet (HDMI wouldn’t be invented for another decade).

Even if you could view a design on the screen, computers weren’t fast enough to allow you to rotate models in 3D in real-time, let alone pinch, swipe and zoom to examine the details of a 3D solid model on a screen. Fast forward 30 years, and we can now put on a virtual reality headset (untethered by wires), virtually teleport into an immersive 3D environment and interact — in real time — with a 3D solid model, zooming, rotating and scaling it while having a conversation — again, in real time — with other people immersed in VR or on their own computer anywhere in the world. That was the sort of thing that made for cutting-edge sci-fi at the time, when movies like Tron, Terminator and Blade Runner were offering visions of what computers and robots might be like in the future — good or bad as it may be.

While I have now seriously dated myself, I hope that I also transported you back to a time when computers weren’t mainstream, product design wasn’t what it is today and prototyping wasn’t easy. Yes, a designer could share drawings and blueprints with machining professionals and manufacturing engineers and get parts made, but it wasn’t quick, and it certainly wasn’t cheap. As a result, product designers had a prototyping problem, and 3D printing provided a real solution. Better yet, 3D printing enabled something unheard of before: rapid prototyping, which got better, faster and cheaper as the technology evolved into the 1990s.

This is why 3D Systems and Stratasys succeeded in bringing 3D printing to the market initially. 3D Systems’ Stereolithography (SLA), or vat photopolymerization as it is generally known, and Stratasys’s Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), or material extrusion, capabilities solved a real problem in the market that many companies experienced during product development — the difficulty of conveying an idea to others during concept design.

At the same time, the importance of idea generation and concept design was gaining recognition as critical to new product innovation, yet there was no way to easily review and critique, let alone hold, 3D models. Along came 3D printing, which solved the prototyping problem and became synonymous with rapid prototyping. Companies that didn’t use 3D printing for prototyping were seen as less as innovative; so, more companies bought more 3D printers. 3D printing manufacturers reinvested the profits to advance the technology and find faster, better and cheaper ways to address the so-called prototyping problem.

With this problem solved, companies shifted their attention to more pressing problems at hand within their organizations. Interest in 3D printing largely died off in the early 2000s as market pull became technology push, and it took over a decade before AM was able to gain widespread attention again. That was the advent of metal 3D printing and the renaming of “3D printing” as “additive manufacturing” about a decade ago.

This is the wave we are riding now, but many have lost sight of the market pull that drove 3D printing’s commercial success. As such, AM is driven by technology push, but it is worth reframing the conversation to refocus on the market pull that drove adoption in the first place. Moreover, if we want AM to compete with conventional manufacturing, we should focus on the manufacturing problems that can be solved better with AM, and how AM can help the machining professionals and manufacturing experts out there. In term, they may find ways to help AM.

Related Content

Additive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreVideo: For 3D Printed Aircraft Structure, Machining Aids Fatigue Strength

Machining is a valuable complement to directed energy deposition, says Big Metal Additive. Topology-optimized aircraft parts illustrate the improvement in part performance from machining as the part is being built.

Read MoreHow 3D Printing Aids Sustainability for Semiconductor Equipment: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

Hittech worked with its customer to replace fully machined semiconductor trays with trays made via DED by Norsk Titanium. The result is dramatic savings in tool consumption and material waste.

Read MoreVulcanForms Is Forging a New Model for Large-Scale Production (and It's More Than 3D Printing)

The MIT spinout leverages proprietary high-power laser powder bed fusion alongside machining in the context of digitized, cost-effective and “maniacally focused” production.

Read MoreRead Next

Profilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read MorePostprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read More