The Third Bucket and the Conversion of Production: A Perspective on Polymer Development for AM

Sabic sees 3D printing taking plastics where they have not gone before, but end-user needs will push the capabilities of 3D printers.

When Keith Cox talks about 3D printing, he refers to it as a “conversion process.” That phrase is an important clue to the role 3D printing is destined to play and the way that companies like his employer will figure in. I recently had a conversation with him about polymer development for additive manufacturing.

Cox works for SABIC, supplier of polymer materials, where his role is senior business manager for AM. From his and this company’s perspective, 3D printing is indeed another conversion process, one more means (like injection molding, blow molding or extrusion) for converting the raw stock from SABIC into a finished good. The different processes behave in different ways and make different demands on the material. And while 3D printing is the newest such process to appear, tailoring materials to the needs of a conversion process is what the company has been doing all along. In this sense, supporting additive manufacturing as it finds a growing role in production is simply more of the same.

But in another sense, AM represents a very different set of challenges for the company. And a different opportunity, because 3D printing promises to grow the very market potential for plastics by expanding what it is possible for plastics to do.

Realizing a polycarbonate delivering roughly similar properties after injection molding or 3D printing entails starting with different formulations of the raw stock tuned to these different processes.

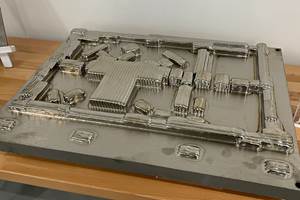

The challenges first: 3D printing is physically a very different operation from other conversion processes. In fact, it is different operations, plural, because AM processes such as selective laser sintering (SLS) and fused filament fabrication (FFF) differ from one another. But both these processes differ markedly from established means of working with plastic such as injection molding. Consider: Injection molding is a hot, high-pressure, short-cycle-time process—the mold slams shut as high-temperature material is injected in. By contrast, both SLS and FFF are processes involving little pressure, run only at the melting or extrusion temperature of the material, with a cycle time lasting so long that the material might remain at or near this temperature for hours at a time or even a day. Thus, realizing a polycarbonate delivering roughly similar properties after injection molding or 3D printing entails starting with different formulations of the raw stock tuned to these different processes.

The other, bigger area of challenge relates to how dynamic additive still is, and how much is still changing. “The maturity level of the AM space today makes material development complex,” he says. “These processes are all evolving. Even in FFF over the last five years, we’ve seen tremendous change in the 3D printing technology. So, we’re at a disadvantage both because there is not a lot of history with these processes and because there continues to be a lot of change.” And that change plays out not only in the machine hardware, but also in the design and simulation software, which are also advancing and can also affect material application.

But it’s all worth it, and the reason why gets to the opportunity. 3D printing is fundamentally different from other conversion processes because there is no tooling needed. There is no mold, for example. That opens the range of part geometries that can be achieved, while reducing the production quantities that might be cost-effective. Because of both areas of freedom, 3D printing will be an enabler for the advance of polymers. By delivering both previously impossible forms and previously impractical solutions, 3D printing will bring plastics into applications it was never able to serve before. Polymer developers obviously see high value in being part of this.

Indeed, the opportunity today falls into three categories, says Cox—“three buckets,” he says—and the most important one is the bucket most affected by the capabilities of today’s machines. Those buckets are:

- Drop-in material replacements. In this area of materials development, the supplier can develop its own, more competitive version of some existing material option—say, its own version of a polycarbonate filament for FFF similar to an existing version.

- New materials for standard print profiles. Within the sets of printer parameters used for established materials, the materials company might be able to engineer new materials with special properties. A new SABIC filament delivering high toughness for consumer electronics and automotive applications is an example.

- New materials leveraging non-standard print profiles. This third category is the most exciting area of material development. The most promising new material options tend to push 3D printers by requiring operational parameters different from the parameter sets locked into established machines—machines that might have been invented with prototyping rather than production in mind. For example, polymers engineered to withstand high-temperature applications need printers not only able to achieve the required high extrusion temperature, but also able to give the operator the capacity to employ that temperature. Another material might require a distinct and specific print speed or layering height. Machines offering an “open format”—that is, user ability to adjust machine settings governing the build—are becoming more valuable as materials advance, Cox says.

Related Content

Two 12-Laser AM Machines at Collins Aerospace: Here Is How They Are Being Used

With this additive manufacturing capacity, one room of the Collins Iowa facility performs the work previously requiring a supply chain. Production yield will nearly double, and lead times will be more than 80% shorter.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreAt General Atomics, Do Unmanned Aerial Systems Reveal the Future of Aircraft Manufacturing?

The maker of the Predator and SkyGuardian remote aircraft can implement additive manufacturing more rapidly and widely than the makers of other types of planes. The role of 3D printing in current and future UAS components hints at how far AM can go to save cost and time in aircraft production and design.

Read MoreBeehive Industries Is Going Big on Small-Scale Engines Made Through Additive Manufacturing

Backed by decades of experience in both aviation and additive, the company is now laser-focused on a single goal: developing, proving and scaling production of engines providing 5,000 lbs of thrust or less.

Read MoreRead Next

Bike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MorePostprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More