Plotting a Pathway to Profitable AM

The cost per pound for a metal AM part may shock you, but that knowledge is essential to help you plan your journey to success with Additive Manufacturing.

If you applied the AM part selection criteria that I gave you two months ago, then you may have a potential candidate for AM on your hands. Ensuring that the material is available, the part fits within the AM build envelope, and the complex features seem to justify the use of AM (versus numerous set-ups or changeovers on a mill, say) only means that you can print it; it does not mean that you should. That is where sticker shock comes into play, particularly with metal AM processes like powder bed fusion.

Several months ago, I shared a simple cost model for laser powder bed fusion that relied only on the weight and height of the part, the cost of the powder, and the cost to operate the AM system. Armed with that information and a few technical specifications about the AM machine (build rate, layer height, recoating time), an estimate for the total cost of a metal AM part could be found by working backward from the industry average for printing (59.2%), pre- (14.4%), and post- (26.4%) processing costs. No CAD model was required, just the material, the weight of the part, and its maximum possible height.

If we ignore the build height for a moment, then estimating the cost of a metal AM part is simply a function of its weight and material, allowing you to develop an estimate of the total cost per kilogram (or price per pound, if you prefer) of any metal AM part. This is where you need to sit down because the numbers are a bit shocking.

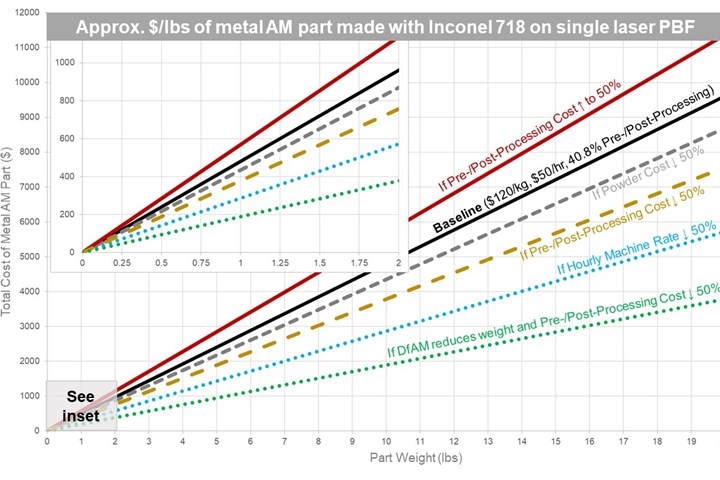

By estimating the total $/lb of a metal AM part, users gain insight to plot a profitable pathway to AM success.

Let’s take Inconel 718 as an example. It costs roughly $120/kg for powder feedstock, and the material density and volumetric build rate for this material on an EOS M290 is 8.15 g/cm3 and 4.2 mm3/sec, respectively. If we decrement the build rate by 80% as advised in my simple cost model and multiple that by the density, then we find that the material build rate is just shy of 100 g/hr (98.58 g/hr to be exact if I did my math and units right). If the machine operating cost is, say, $50/hr fully burdened, then the printing cost per gram is $0.51/g or $507/kg. Don’t believe me? Do the math.

Sadly, we are not done yet. The material cost and machine cost are only 59.2% of the total cost based on the industry averages I cited earlier. That means the total cost of a metal AM part is found by adding material cost ($120/kg) and machine cost ($507/kg) and multiplying by 1.689 (= 1/0.592). Note that if the industry average printing cost was 50% of the total cost (vs. 59.2%), then the pre-/post-processing cost would be 50%, which means the total cost would simply be double the sum of machine cost and material cost—much easier math to do.

Putting this all together, a rough estimate for the total cost per kilogram of a metal AM part made with Inconel 718 is $1060/kg { = ($120/kg of material + $507/kg of machine time)/0.592} or $1.06/g. That’s $480/lbs for those who prefer English units. Ouch! Reality bites, especially since we have ignored several cost drivers, including build height which drives up machine time even higher.

Fortunately, by knowing this number and where it comes from, you can begin to plan your path to profitability. By varying some of these assumptions, you can plot the cost-per-kilogram as I have done in the figure and identify ways to achieve your cost target. How much cheaper does the material need to be? How much faster does the machine need to be or can I amortize (or depreciate) the cost of the machine differently to reduce its hourly rate? Better yet, how do I reduce the pre- and/or post-processing costs to minimize the multiplier? My personal favorite: how can I use design for AM (DfAM) to minimize volume, build time, material cost, and pre-/post-processing cost all at once? Again, you now see why DfAM is the value multiplier for AM because it is the fastest way to move down these cost curves.

If you run the numbers for Ti-6Al-4V, AlSi10Mg, and 17-4PH using metal 3D printing material data from EOS, you get $1347/kg, $2285/kg, and $1287/kg, respectively, for a laser powder bed fusion with a single laser. This might surprise you given that Ti-6Al-4V is the most expensive material ($360/kg) compared to AlSi10Mg ($78/kg) and 17-4PH ($91/kg). The difference lies in the build rate for Ti-6Al-4V, which is among the fastest available in large part due to thicker layers (60mm vs. 30mm and 40mm, respectively). The low build rate and low material density of aluminum combine to make it one of the most expensive metals to use in AM even though the powder is the cheapest. This just goes to show you that a material that may have been too expensive for conventional manufacturing may be within reach when you use AM.

While the cost model is admittedly simple and there are lots of underlying assumptions, it gives insight into AM that you did not know you had. The ability to run a sensitivity analysis or ask “what if” questions with this approach can help a company navigate the pathways available to them and find one that leads to a profitable part—if not now, then in the future as machines get faster and costs come down.

While finding a pathway to profitable AM is good, don’t lose sight of the fact that AM is only way to make the part a reality. The real challenge lies in being more cost-effective than the other manufacturing options available to you. By knowing the cost per kilogram, though, you can set your sights for success with AM—once the sticker shock wears off.

Related Content

3D Printing Molds With Metal Paste: The Mantle Process Explained (Video)

Metal paste is the starting point for a process using 3D printing, CNC shaping and sintering to deliver precise H13 or P20 steel tooling for plastics injection molding. Peter Zelinski talks through the steps of the process in this video filmed with Mantle equipment.

Read MoreThis Year I Have Seen a Lot of AM for the Military — What Is Going On?

Audience members have similar questions. What is the Department of Defense’s interest in making hardware via 3D printing over conventional methods? Here are three manufacturing concerns that are particular to the military.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreAM 101: What Is Binder Jetting? (Includes Video)

Binder jetting requires no support structures, is accurate and repeatable, and is said to eliminate dimensional distortion problems common in some high-heat 3D technologies. Here is a look at how binder jetting works and its benefits for additive manufacturing.

Read MoreRead Next

3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read MoreCrushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read More