How a Prototyping 3D Printer Became a Production 3D Printer

Boyce Technologies was already a leader in manufacturing communications devices, but 3D printing and a partnership with BigRep have helped it remain competitive—first through prototyping, and now in production.

By the time the job came to Boyce Technologies, there were only two weeks left in its nine-month timeline. Another contractor had fallen behind on the work, and so the customer—the New York City Transit Authority—approached Boyce, hoping the Long Island City company could manufacture the products in time. Without hesitation, company founder Charles Boyce agreed to take on the job.

The product in question was a totem with a digital screen used to display maps and advertising information to commuters on city streets. The system was complex, requiring the manufacturing and assembly of many different metal, plastic and electrical components. Fortunately, it was just the type of product that Boyce Technologies is positioned to tackle. And it was the type of timeframe Boyce is now equipped to handle as well, thanks in part to large-format 3D printing and the way that its 3D printing capability has advanced from rapid prototyping to rapid production.

Communication Is Key

Boyce Technologies was founded in 2008 by Charles Boyce, an engineer with experience in telecommunications safety equipment (think emergency phones and similar communication devices that might be found in subway terminals, at bus stops or in train stations). The company’s 120 employees manufacture complete communications systems from its 150,000-square-foot facility in Long Island City, just a few train stops from the heart of Manhattan.

Within this building is an extensive suite of manufacturing technologies, including machining, injection molding, thermoforming, powder coating, and laser and waterjet cutting equipment. “About the only thing we outsource is extruded aluminum,” says Ajmal Aqtash, director of advanced robotics. “We’ve gambled big on establishing a wide range of technologies that reflect not just our current needs, but our needs in the near future.”

In all of its equipment purchases Boyce has pursued a desire to partner with its suppliers. “Simply put, we’re not buying a piece of hardware or equipment or technology,” Aqtash says. “We’re actually buying into the relationship.” The company has established close relationships with suppliers such as Hurco (manufacturer of its 30 CNC machine tools), ABB (supplier of its several robotics systems) and Trumpf (maker of its laser cutting equipment).

But until 2017, additive manufacturing had no role at Boyce Technologies. Tooling and production metal parts were machined from aluminum or steel; polymer parts were made with injection molding or thermoforming. But when Aqtash came on board, he began to see areas where a 3D printer would make things easier. Boyce often manufactures full-scale prototypes of communication devices that can be carried down into a subway station, for example, to check the fit for future site installation.

“If you’re making something like that out of metal, there’s a lot of time and effort associated with that,” he says. “It is time-consuming on the front end, not to mention the size and weight of these parts.” At his suggestion, Boyce began to look at large-format 3D printers that could make these prototypes instead, offering a lighter-weight result that wouldn’t take up capacity on a machining center. A large-enough printer with the right material compatibility could also fill another need: manufacturing thermoform tooling for PETG shrouding and other end-use parts, either as an alternative to aluminum molds or a stop-gap solution until aluminum tooling can be made.

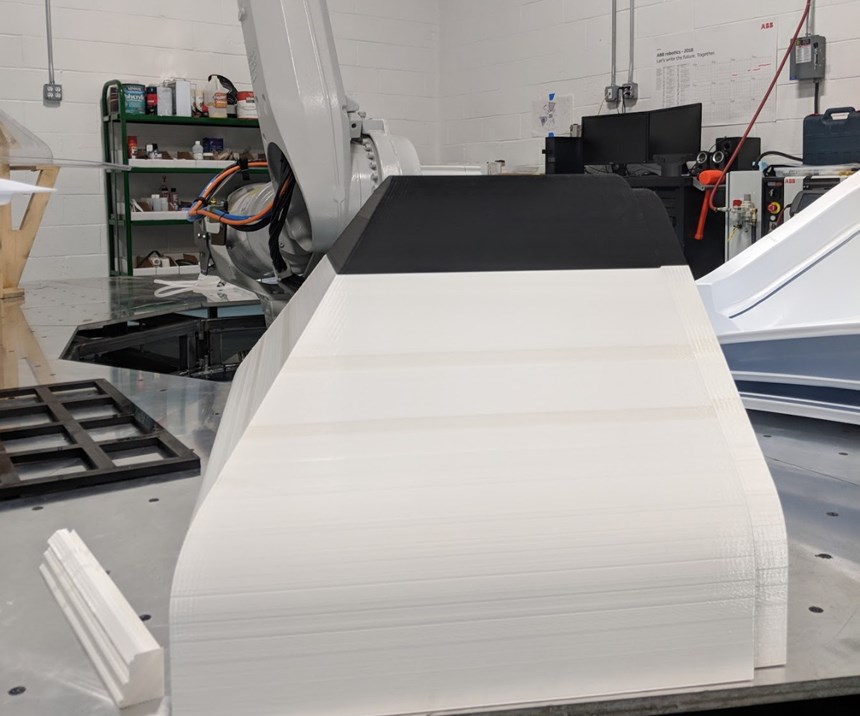

The company decided to purchase a BigRep Studio system, which was installed late in 2017. In addition to the printer’s large build volume (measuring 1,000 by 500 by 500 mm) and support for engineered materials, Boyce Technologies chose this machine for the relationship it has been able to establish with BigRep. “I think more than anything it was their willingness to listen and give us a voice within the additive space,” Aqtash says. As a company new to AM, Boyce has been able to voice its concerns and rely on BigRep’s expertise. “While it might have started with large-format 3D printing, the partnership ultimately has to do with that willingness to understand what our interests are and the next generation of technology that is going to keep us competitive.”

“The speed at which we were able to move...began to redefine the idea of rapid prototyping. We’re actually doing rapid production.”

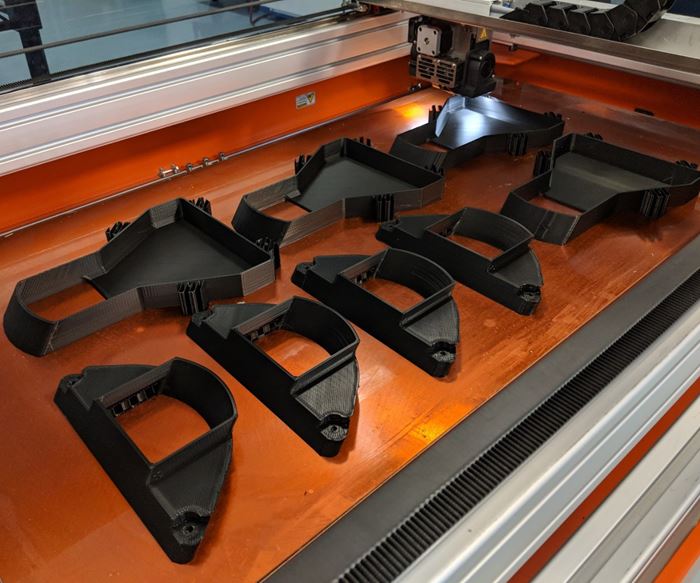

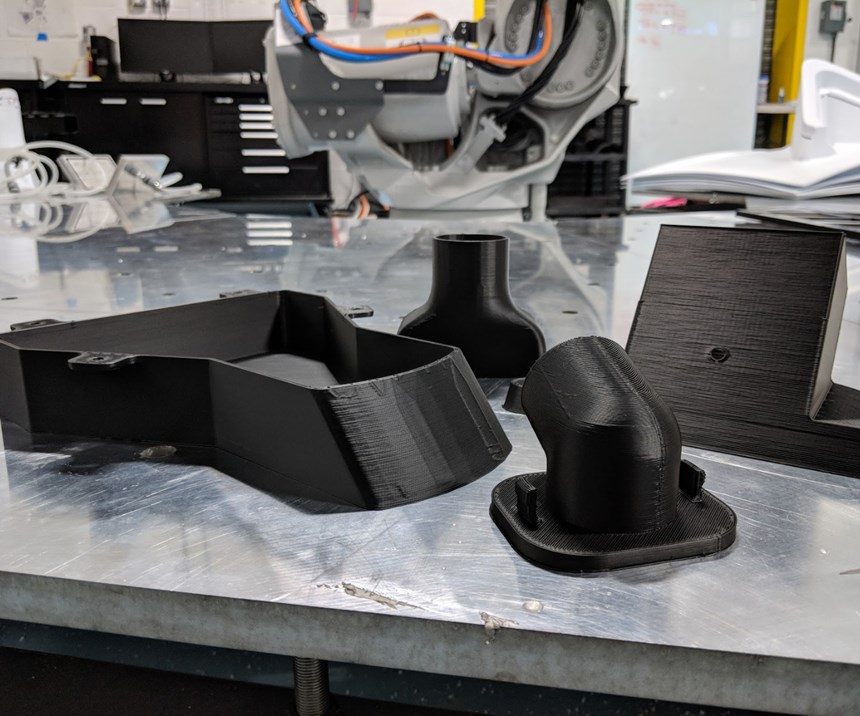

Boyce began to leverage that competitive advantage for more than just prototyping and tooling soon after the printer’s installation. A digital kiosk made for Verizon presented an early opportunity to use the Studio system in production. “We had traditionally understood certain parts to be metal, but as we began to look at it more carefully, there were things that weren’t structural and didn’t need to be of a certain density,” Aqtash says. “These could be light, and maybe of a more organic shape. For anything in terms of air handling, exhaust or intake, we chose to go with a 3D-printed approach.”

The final kiosks featured half a dozen parts that are fully 3D-printed, including air valves, conduits and exhaust systems. “That kind of started the culture change,” Aqtash says. “The speed at which we were able to move through design engineering and into production began to redefine the idea of rapid prototyping. We’re actually doing rapid production.”

From Rapid Prototyping to Rapid Production

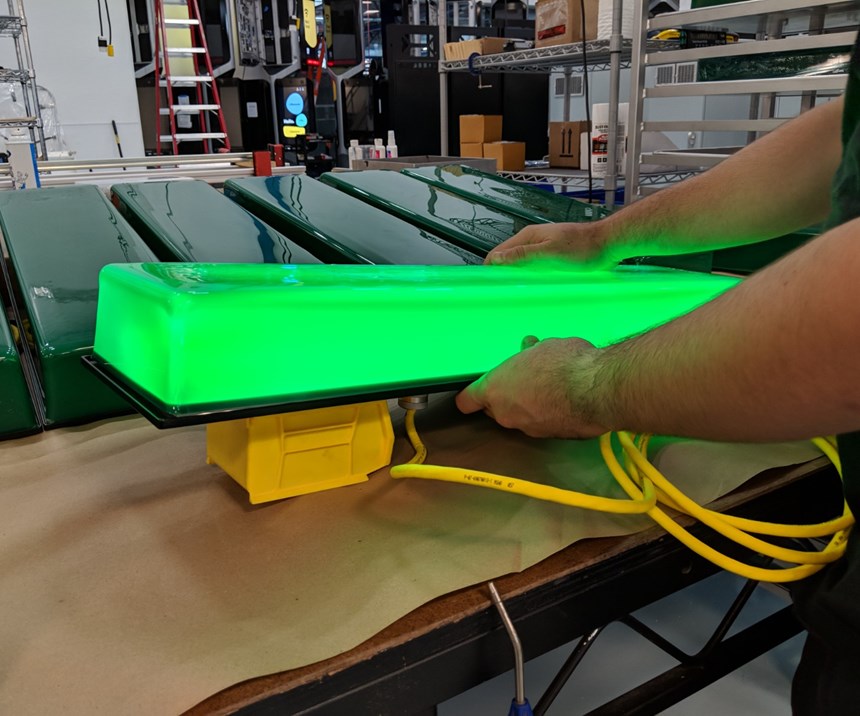

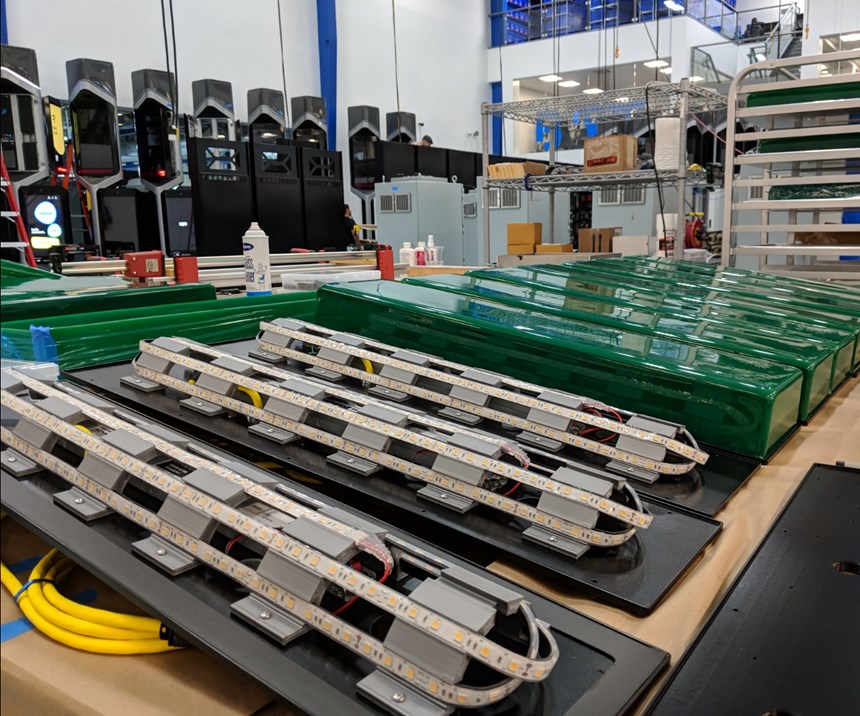

That “rapid production” attitude helped save the day in the rush job to build the NYC Transit totems. Each of these systems features a green acrylic cap on its top that houses an LED strip for illumination as well as a sensitive antenna instrument.

“That antenna required that no metallic material be in front of it, which would disrupt the reception,” Aqtash says. “The brackets for the LED strip and the housing for the antenna had to be plastic, and we had only a short period of time for design, engineering and production. 3D printing presented a solution.”

Using its BigRep Studio system, Boyce was able to prototype curved mounting brackets for the LED lights to illuminate the cap, and then move straight into manufacturing these parts on this same platform. 3D printing these brackets allowed them to be made quickly and more cost effectively than injection molding or machining, while also meeting the no-metal requirement above the antenna.

“It was a natural segue for us to implement this within that short period of time,” Aqtash says. “In the end we didn’t go through thermoforming. We didn’t go through injection molding. I think we made one prototype and everything came together, and then we just jumped right into production. If additive technology wasn’t part of the equation here, I just can’t see that happening.”

“What we initially thought was a prototyping machine is actually a production machine.”

Ultimately Boyce was able to deliver the completed totems with their 3D-printed brackets within two weeks. Aqtash points to this situation as an indicator of how 3D printing is viewed now at Boyce Technologies. “Creating an additive part was very natural for us,” he says. “We weren’t stretching. We’ve normalized it, in a sense.”

But normalization isn’t the end for 3D printing at Boyce Technologies. The company is already looking for the next way to push the envelope, again leveraging its partnership with BigRep. The company recently became the first commercial site to install the BigRep Pro, a next-generation printer that incorporates Bosch-Rexroth motion control and is said to be 10 times faster than the Studio system. That’s only the beginning. Boyce has plans to experiment with robot-based 3D printing for larger parts, automated finishing and more. The Studio printer will remain a key part of the business even as these experiments go on.

“We’re now using it 90 percent of the time for production and only a small percentage for prototyping,” Aqmal says. “What we initially thought was a prototyping machine is actually a production machine.”

Related Content

Bike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MoreFaster Iteration, Flexible Production: How This Inflation System OEM Wins With 3D Printing

Haltec Corp., a manufacturer of tire valves and inflation systems, finds utility in 3D printing for rapid prototyping and production of components for its modular and customizable products.

Read MoreIndyCar's 3D Printed Top Frame Increases Driver Safety

The IndyCar titanium top frame is a safety device standard to all the series' cars. The 3D printed titanium component holds the aeroscreen and protects drivers on the track.

Read More4 Weeks from Design to Molded Part for Medical with Metal 3D Printed Tooling

Mold builder Westminster Tool applied the Trueshape process from Mantle to produce tooling to take a medical device from prototype mold to full-scale production in a matter of weeks.

Read MoreRead Next

3D-Printed Prototypes Become the Parts with Carbon Fiber Filled Filament

Utah Trikes, a retailer and manufacturer of trikes and quads, has grown its custom business using FDM Nylon 12CF to produce end-use composite parts that formerly would have required moldmaking.

Read MoreAutomated AM System Looks Toward Future of Industrial Production

A partnership between 3D printer manufacturer BigRep and Dutch research organization TNO is creating an automated additive manufacturing system.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)