For Stratasys, Acquisition of Origin Part of Strategy Focused on Production and Polymer Materials

Americas president Rich Garrity describes how the two additive manufacturing technology companies came together (COVID-19 helped), along with the value of protecting one culture while allowing another to change.

What does it mean that Stratasys purchased Origin? The two companies became one at the end of last year, and another more recent acquisition followed this one (more below).

In part, the answer to the question is obvious: The move represents a commitment by Stratasys to end-use part production as the role of additive manufacturing (AM) and the most promising opportunity for the company to serve. Scale production is the purpose of the polymer AM platform Origin developed.

But in part, the answer is also more subtle. For Stratasys, this move relates to a clarifying of goals, along with the prospect of current and future culture change for this established supplier of 3D printing equipment, software and materials.

Rich Garrity, president for the Americas with Stratasys, seen here with an Origin machine. Photo Credit: Stratasys

I recently spoke with Rich Garrity, president for the Americas with Stratasys, about the acquisition. He says the move is part of a strategy spelled out by company CEO Yoav Zeif. That aim is to “lead in polymer 3D manufacturing,” Garrity says, adding that this vision “offers a clear north star for our way forward.”

Describing Stratasys as an “established” 3D printing equipment maker is inarguable. For a time, the company was synonymous with what were then the accepted uses of industrial polymer 3D printing: tooling and prototypes. To find a machine shop using a 3D printer bigger than a desktop model was to find it using a Stratasys machine. However, the scope of credible applications for AM has significantly changed — to the extent that Stratasys has committed to pursuing different applications of 3D printing now than it once did, and serving those customers in a different way.

“Production AM will be our focus,” Garrity says. “Future investment will be in that area. And we will take a solution-driven approach to the market,” he says, as contrasted with a machine- or product-driven approach.

“The model that got us where we are is not the model that will get us where we are going.”

“The model that got us where we are is not the model that will get us where we are going.”

But being solution-driven requires having access to all the potential solutions. This is where Origin comes in, and this move is part of a larger picture. Out of the polymer AM processes, polymer deposition, or fused deposition modeling (FDM), is the one Stratasys has — the one it has led in. Now, Origin brings vat polymerization, or digital light processing (DLP), a very different means of 3D printing in polymer. Meanwhile, a major investment in Xaar brings Stratasys powder bed fusion 3D printing and, the most recent acquisition of all of these, RP Support brings stereolithography.

For Stratasys and Origin, the move from relationship to purchase happened quickly, and essentially happened both during and thanks to the pandemic. The two companies worked together on 3D printed swabs for COVID-19 testing. Origin was able to rapidly develop a workable swab design and Stratasys had the organizational reach to market the swabs to hospitals and other institutional users. It became clear this model for working together offered a way forward. Origin, a Silicon-Valley technology startup, excels at product innovation, and has continued to refine its platform for polymer part production and for rapid materials development for DLP. Stratasys, meanwhile, has the 3D printing sales organization Origin might never have had the ability to grow on its own.

That much made for a promising fit. The concern then became cultural.

Garrity says the Origin leadership “wanted to make sure the DNA of Origin stayed in place, that they wouldn’t get ‘sucked into the Stratasys machine.’ And we wanted that, too.” He says Stratasys responded in the way it designed the organization around the acquired company — keeping with a product line or business unit model for internal organization, to allow Origin to continue operating as it has been.

Yet while the concern is cultural, Garrity says he sees an opportunity there, too. Origin developed a production AM system, but importantly, the focus of that system is materials. Origin’s platform offers both software control over parameters important to material behavior and a level of access and openness allowing independent material companies to use this platform to realize their own aims.

The success of AM for production depends on allowing customers to work with exactly the material they want, and Stratasys cannot develop all these options on its own.

That openness does not match Stratasys’ historic approach to materials. The company has developed FDM materials internally. But the success of AM for production depends on allowing customers to work with exactly the material they want, and Stratasys cannot develop all these options on its own.

So, Garrity hopes Origin is not too isolated within its new owner, so that the team of approximately three dozen who were employees of the company can help change the larger organization. The important differences between the two companies go beyond an open approach to materials; RP Support brings something like this same openness as well. Origin’s software-based approach to machine development and control is even more distinctive, as is its entrepreneurial team. Garrity cites the “cultural DNA,” and frames the opportunity he sees in this with the question, “How do we get Origin to rub off on the broader Stratasys?”

Related Content

At General Atomics, Do Unmanned Aerial Systems Reveal the Future of Aircraft Manufacturing?

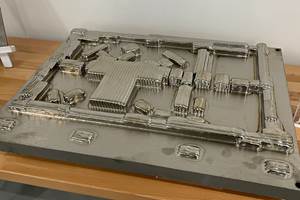

The maker of the Predator and SkyGuardian remote aircraft can implement additive manufacturing more rapidly and widely than the makers of other types of planes. The role of 3D printing in current and future UAS components hints at how far AM can go to save cost and time in aircraft production and design.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

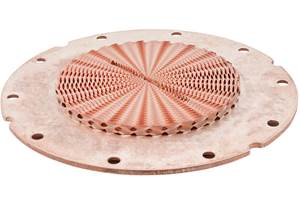

Read MoreWith Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM), Cooling Technology Is Advancing by Degrees

San Diego-based Fabric8Labs is applying electroplating chemistries and DLP-style machines to 3D print cold plates for the semiconductor industry in pure copper. These complex geometries combined with the rise of liquid cooling systems promise significant improvements for thermal management.

Read MoreThis Drone Bird with 3D Printed Parts Mimics a Peregrine Falcon: The Cool Parts Show #66

The Drone Bird Company has developed aircraft that mimic birds of prey to scare off problem birds. The drones feature 3D printed fuselages made by Parts on Demand from ALM materials.

Read MoreRead Next

How Test Swabs Became 3D Printing's Production Win: The Cool Parts Show #15

Nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 testing are one of the best production cases for 3D printing we've seen, pandemic or otherwise. Why AM is winning on speed, functionality and collaboration.

Read MoreThe Promise of Full Polymerization in Resin 3D Printing

Origin’s platform isn’t just another resin 3D printer based on digital light processing (DLP). Through hardware, software and material partnerships, the company is changing what is possible inside a photopolymerization printer.

Read More