Sarah Wells is COO of Spectrum Dental Printing in Worthington, Ohio, a 3D printing lab adjacent to a dental practice that is directly 3D printing dental models as well as removable devices. Her lab is a key part of the practice’s transition toward a digital dentistry workflow.

You probably don’t think of going to the dentist as an exercise in mass customization, but technically, it is. Many dental items such as bridges, dentures and mouth guards are made specifically for the patient, customized to the size, shape and perhaps even color of each mouth. When so many other items in daily life are simply mass produced identically at scale, how has dentistry sustained this exceptionally personalized experience?

Through manual labor, skill and analog processes, it turns out. These techniques have worked for decades, but pose trade-offs. They require hours of work, which translates to wait time for both doctor and patient, and may subject the patient to discomfort during the process. We dental patients have been willing to wait and suffer in order to receive these bespoke items, since there has been no other way.

But what if dentistry could be faster? What if it could be more precise? What if it could offer a more comfortable patient experience?

This is the stage of dentistry we are entering right now, says Sarah Wells. Wells is the digital technology specialist at Spectrum Dental and Prosthodontics, as well as the COO at Spectrum Dental Printing. This second business is a dental lab adjacent to Spectrum Dental’s regular practice that is dedicated to 3D printing dental models and removable devices such as occlusal guards, temporary dentures and surgical guides. Using a digital dentistry workflow enabled by 3D scanning technology as well as her lab’s five Formlabs 3D printers, Spectrum Dental is improving dental care for its own patients and now those at other practices, too.

An Analog Path to Customization

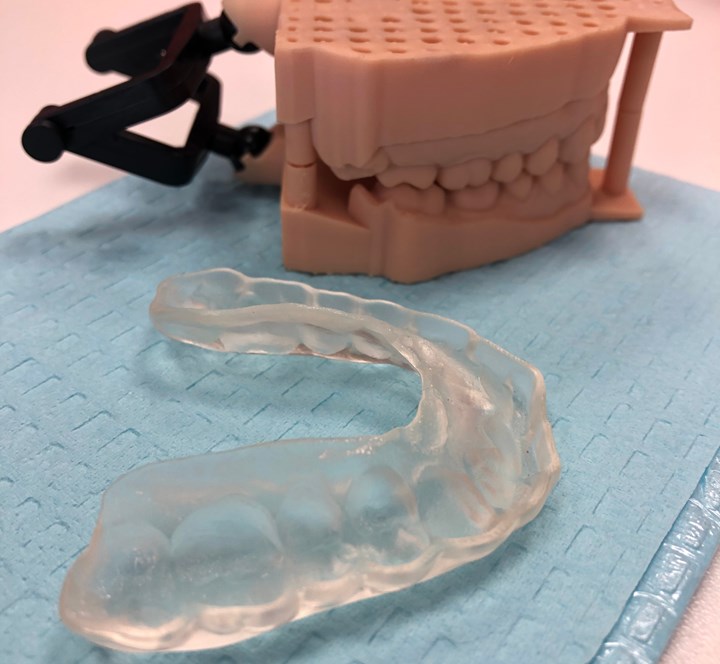

To understand what a new, digital dentistry process might mean, it’s helpful to look at the conventional way of doing things. Consider dental models. Typically cast from dental stone, these models are positive reproductions of a patient’s teeth and/or gums that serve as the basis for developing implants like bridges as well as removable devices such as dentures and occlusal guards, mouth guards worn at night to prevent tooth grinding.

This plaster-like model reproduces the teeth and gums of a particular patient. Models are used to get a better look at conditions inside a mouth as well as to develop devices like dentures or guards. With conventional processes, the model often becomes sacrificial tooling for making those devices.

The conventional process for producing dental models looks like this: The doctor places a tray filled with putty-like alginate in the patient’s mouth to obtain an impression of the teeth and gums. The material has to be allowed to harden while in the mouth, which takes several minutes and can be uncomfortable for the patient. Then, the impression is cleaned and trimmed. Once the impression is made, a technician mixes and pours the stone into the cavity to make the final model.

Obtaining a model this way is not prohibitively slow or expensive, but it does require manual work and skill. The doctor must work carefully while being cognizant of the patient’s comfort during the process. “The impression is all or nothing,” Wells says. “If the patient gags or moves, we have to start over. We might even make two or three impressions to make sure we’ve got it.”

Even if all goes smoothly, the final model still may not be completely accurate. The alginate used to capture the impression can cause teeth or tissue to move out of position, or even pull out teeth if they are loose. Bubbles and voids in the stone mixture can negatively impact the end result as well.

Without a good model to work from, the technician may end up developing a device that won’t work for the patient and the process will need to start over.

That end result is often not just the model itself, because these models are also the starting point for developing dental devices. If the patient requires dentures, for instance, the technician applies wax to the model and carves it into the desired shape. Then, the waxed model is placed into a flask and surrounded with plaster. The wax is melted away, and the finished mold can be filled with resin to create the dentures. For occlusal guards, the stone model actually becomes a thermoform mold; a thick sheet of acrylic is formed over the plaster then cured, trimmed and polished to form the guard. In both cases, the model serves as sacrificial tooling and is lost once the process is complete. Without a good model to work from, the technician may end up developing a device that won’t work for the patient and the process will need to start over with impressions.

This is the process Spectrum Dental now has largely replaced.

The Digital Dentistry Alternative

The 3D printing lab is just part of Spectrum’s digital dentistry workflow, which in fact started with 3D imaging. The practice has a desktop 3D scanner that can capture data from models made with traditional impressions, but also uses intraoral scanners that make it possible to move away from taking impressions altogether. Once the 3D data is acquired through one of these scanning methods, a dental lab can use it to create G code for a dental CNC mill or an STL file for a 3D printer.

Dr. Bradley Purcell, the owner and practicing prosthodontist of Spectrum Dental as well as president and CEO of the 3D printing lab business, teaches continuing education classes for dentists on scanning and the digital workflow among other topics. Spectrum is currently equipped with software and handheld intraoral Trios scanners from 3Shape. Each scanner is about the size of an electric toothbrush, and allows staff to capture digital three-dimensional images of patients’ mouths by simply moving the scanner’s camera along the teeth and jaw. The scan is instantly displayed on a computer monitor with any missing areas highlighted so the user can check that all needed data has been captured.

Spectrum Dental has four Trios wireless scanners that can be paired with any workstation computer to capture a full scan of the patient’s mouth in a matter of minutes.

This digital scan takes the place of analog dental impressions. In addition to shortening the process of data capture, the scan has other benefits. The scanner never touches the patient’s teeth, so teeth are protected from movement and the scan is more accurate. Scanning can also start and stop as needed for patient comfort, without losing any data.

Once complete, a technician can modify the data cloud to trim excess information, and postprocess it into an STL file. The original data cloud is stored in the software for 45 days, while the STL file is preserved indefinitely. If a model is needed, Wells can import the file into PreForm, Formlabs’ print preparation software, to place the part(s) on a build plate, add supports and send the job to one of the printers within about 15 minutes.

Models are typically printed at about a 30-degree angle, using tree-style supports on a flat raft. This strategy allows for good resin drainage, and makes part removal much faster and easier than removing each tree from the build plate individually.

A complete dental model (both top and bottom jaw) can be printed in about 7-8 hours, so Wells often runs these jobs overnight. While this takes longer than pouring a stone model, the process is hands-off and doesn’t require human involvement. In the morning, she can remove the prints from the build plate and place them into a washing unit filled with alcohol to clean off excess resin. After two rounds of washing, the parts go into a curing unit for about half an hour to set the resin. The supports are removed by hand, and models get a quick polish before they are ready to use.

The digital workflow has a number of benefits for both the practice and its patients, Wells says. On the business end, the scanning process saves time when patients are in the chair, and the data is more accurate than the form created by a physical mold, allowing for devices that fit and work better. The 3D printers free up work hours that would otherwise be spent manually casting these models. And it’s easier — an important point, because like many industries that rely on skilled labor, dentistry is facing a shortage of workers with the training necessary to make and fine-tune dental devices by hand. “We’re lucky as an industry that digital came up when it did,” Wells says, citing the number of dental technicians advancing toward retirement and impending loss of their skills.

The larger payoff, however, is an improvement in patient care. Spectrum Dental now routinely scans patients as part of their regular exams; doctors can then overlay new scans with previous data to check progress or identify changes. It’s also become a habit to print a model of a patient’s mouth when the dental lab is making a guide or other device. Why? “Anything we can do to save time for the doctor at the chair is a win,” Wells says. Having the model on hand allows the lab to check the fit of any device without having the patient on-site. If it doesn’t work, adjustments can be made or the device reprinted before the patient returns. Keeping a library of STL files on hand also makes it possible to remake a model or device at a moment’s notice, so patients can be cared for much more quickly.

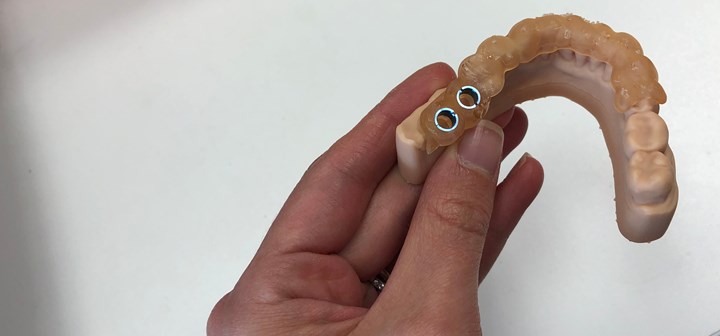

It’s become standard practice to automatically print a model of the patient’s mouth when making a device, so that the lab can check the fit and make adjustments before the patient returns. Surgical guides like this are a newer offering from Spectrum Dental Printing. They are printed with Formlabs’ Dental SG resin which can be processed in an autoclave; standard metal inserts are added after printing.

More Than Models

Spectrum Dental Printing originally started out with just two printers, making models for three of the dentists at the practice. Now, Wells is producing models, bite guards, surgical guides and even temporary dentures for Spectrum Dental as well as outside practices.

Wells removes a model from one of the lab’s washing stations. Each print is washed twice in isopropyl alcohol. Models are rinsed in the same unit for both washes, while items made with biocompatible resins must be cleaned in two stages in a separate pair of washing units.

The lab has grown to include four Form2 printers, a new Form3 model, three washing stations (one for the model material and two for processing biocompatible materials), and one curing unit. Wells is currently printing with Formlabs’ model resin as well as its biocompatible materials for mouth guards, surgical guides and dentures.

Right now, the mix of work is about 70% in-house items and 30% for external customers, Wells says. The digital workflow applies even to the outside-facing business — dentists who want to order models, guards and surgical guides need to provide STL files generated from a direct scan of the patient’s mouth, not impressions or conventional stone models. In a typical week, she is printing 15 to 18 occlusal guards and 60 to 70 models.

While removable dental devices have historically lacked the regulation of, say, hip or spine implants, the move toward digital may change that. When guards and other devices were made manually with analog tools and technology, standardizing the process was difficult. A digital dentistry workflow, however, makes it easier to implement a repeatable process. Although as yet Spectrum Dental Printing does not need ISO certification or FDA registration, Wells is working toward documenting its processes and bringing the lab into FDA compliance in anticipation of future requirements — and potentially, additional staff. The lab is preparing to move to a larger space in early 2020, and expects to add new printing technology soon too.

Making the shift to digital dentistry is an ongoing process for Spectrum Dental Printing and the dental practices it serves, but Wells believes the change is worth it. What was already a custom process has been made faster, easier and more convenient for the doctors, technicians and, most importantly, patients involved.

“It’s better patient care,” she says. “This will change how we treat people.”

Removable dental items such as occlusal guards do not face the same regulation as other medical devices. That could change as dentistry becomes more digital, and therefore more repeatable and trackable.

Related Content

Micro Robot Gripper 3D Printed All at Once, No Assembly Required: The Cool Parts Show #59

Fine control over laser powder bed fusion achieves precise spacing between adjoining moving surfaces. The Cool Parts Show looks at micro 3D printing of metal for moving components made in one piece.

Read More3D Printed Spine Implants Made From PEEK Now in Production

Medical device manufacturer Curiteva is producing two families of spinal implants using a proprietary process for 3D printing porous polyether ether ketone (PEEK).

Read MoreOvercoming Challenges with 3D Printing Nitinol (and Other Oxygen-Sensitive Alloys) Through Atmospheric Control

3D printed nitinol has potential applications in dental, medical and more but oxygen pickup can make this material challenging to process. Linde shares how atmospheric monitoring and the use of special gas mixtures can help maintain the correct atmosphere for printing this shape alloy and other metals.

Read MoreQ&A With Align EVP: Why the Invisalign Manufacturer Acquired Cubicure, and the Future of Personalized Orthodontics

Align Technology produces nearly 1 million unique aligner parts per day. Its acquisition of technology supplier Cubicure in January supports demand for 3D printed tooling and direct printed orthodontic devices at mass scale.

Read MoreRead Next

Topology Optimized 3D Printed Spine Implant: The Cool Parts Show #2

Medical contract manufacturer Tangible Solutions shares a titanium 3D printed spine implant with an unusual lattice structure in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreIs Your Dentist a Manufacturer?: The Cool Parts Show #10

Dental devices have always been custom, but 3D printing is disrupting how they are made. We go inside a dental lab in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreFormlabs Process to Deliver Custom 3D-Printed Earbuds

A process that uses the Form 2 3D printer and Formlabs resin to produce custom silicone ear molds is part of the "year of mass customized earbuds."

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)