Density Parameters in AM: Measurement and Relevance

For powder material used in additive manufacturing, “density” has various meanings. The different density definitions are useful in different ways.

When it comes to determining density parameters to support additive manufacturing (AM), it is easy to measure mass, whether the sample is a finished component or an aliquot of powder. However, measuring volume is less straightforward and, in fact, volume can be measured in various ways, producing different values of density. Understanding how alternative density parameters are measured is valuable for AM, to optimize raw material choice, process performance and the characteristics of finished components.

Bulk Density

Starting first with a powder feed, bulk density—the mass of powder divided by the volume the powder occupies—can be determined by pouring a known mass of sample into a measuring cylinder. Bulk density is a useful measure for comparing powder specifications and can provide insight into AM bed formation and powder flowability, a critical property for both raw and recycled materials. The volume measured includes the interstitial space between powder particles, so bulk density is heavily dependent on particle packing, which in turn is influenced by particle size and shape.

The inclusion of interstitial space, however, means that bulk density values depend on the extent of aeration or consolidation of the sample. Tapping or the application of pressure encourages the sample to consolidate tighter, and will increase bulk density. This effect can introduce variability in bulk density measurements and allow relevant measurement for a specific application. For example, bulk density can be measured under a low consolidation pressure to generate representative values for packaging or for metering from a hopper.

True (Absolute) Density

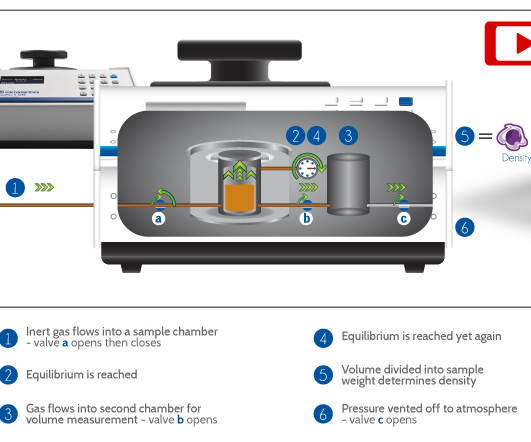

When it comes to assessing how a powder behaves during sintering, as particles melt and fuse to form the finished component, bulk density becomes less relevant and true density, also referred to as absolute density, is more informative. This is the density parameter based on the actual amount of material present and is simply and reliably measured using the technique of gas pycnometry. Gas pycnometry involves precise measurement of the volume of gas (typically nitrogen or helium) displaced by the sample.

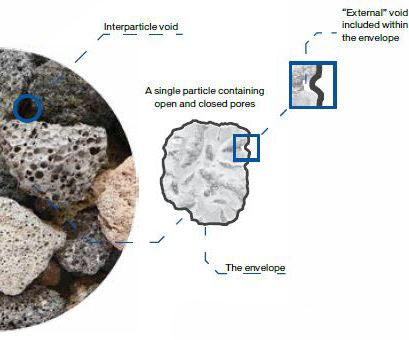

If the displacement gas has access to void spaces in a powder sample, via accessible porosity, then gas pycnometry will measure a higher volume than if the sample has negligible porosity, or closed pores. The resulting lower density is referred to as a skeletal (or apparent) density. Where the porosity of a feed material is a significant concern, it can be studied using the mercury porosimetry technique. Various AM feeds, including most metal powders in the sub-45-micron size range, have low porosity, which means that gas pycnometry tends to return true density values.

Envelope Density

Finished components are often associated with an envelope density which, as the name suggests, is based on the volume defined by an envelope around the sample of interest. It too is measured using pycnometry, but with a dry, free-flowing powder as the displacement media. This powder is composed of small rigid spheres that flow around the component but will not penetrate the intricacies of what are often highly irregular structures. The ratio of envelope to true density therefore indicates the degree of porosity of the component, a metric that is typically of prime importance in defining performance.

Whether bulk, true, or envelope density measurements are required, there is proven instrumentation to help, with pycnometry valuably presented in versatile systems for density measurement that enable the measurement of multiple density parameters. These can provide detailed insight into AM materials and products to directly support the more efficient application of this transformative manufacturing technique.

Related Content

The AM Ecosystem, User Journeys and More from Formnext Forum Austin: AM Radio #43

Sessions and conversations at the first U.S. Formnext event highlighted the complete additive manufacturing ecosystem, sustainability, the importance of customer education, AM user journeys and much more.

Read MoreImplicit Modeling for Additive Manufacturing

Some software tools now use this modeling strategy as opposed to explicit methods of representing geometry. Here’s how it works, and why it matters for additive manufacturing.

Read MoreNIOSH Publishes 3D Printing Safety Guide for Nonindustrial Settings

NIOSH has published a 3D printing safety guide for small businesses and other additive manufacturing users such as makerspace users, schools, libraries and small businesses.

Read MoreThe New Misperceptions Of AM: AM Radio #35

Tim Simpson and Peter Zelinski discuss a way additive manufacturing has advanced: The misperceptions have shifted. Knowledge of AM among manufacturers is more sophisticated now. The concerns that inform the perceptions of newcomers have therefore changed.

Read MoreRead Next

Postprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read MoreProfilometry-Based Indentation Plastometry (PIP) as an Alternative to Standard Tensile Testing

UK-based Plastometrex offers a benchtop testing device utilizing PIP to quickly and easily analyze the yield strength, tensile strength and uniform elongation of samples and even printed parts. The solution is particularly useful for additive manufacturing.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read More