One Small Step for Metals, One Giant Leap for AM

Eliminating support structures for metal parts expands pathways to profitable AM.

For most manufacturing processes, the more complex the part, the more expensive it will be to produce. This is not a surprise. Machining a complex part can require a combination of set-ups, fixtures, jigs, tooling, etc., which all drive up cost. Similar logic applies to injection molding: the more complex the part, the more expensive the tooling, the more expensive the part. Same goes for casting, forging, stamping and pretty much every manufacturing process we currently have at our disposal.

With additive manufacturing (AM), “the data is the tooling” as Patrick Dunne, vice president of advanced applications at 3D Systems eloquently said in one of his LinkedIn posts last year. Manipulating “the data” to change “the tooling” and produce a different AM part is relatively easy compared to having to remake fixtures, jigs and other (physical) tooling for conventional manufacturing. Because it is so easy in comparison, the cost is negligible, and by extension, “the tooling” for making complex parts with is essentially zero. Consequently, it is easy to see why many tout “free complexity” when it comes to AM, finally enabling “economies of one.”

While the logic makes sense and has driven much of the hype behind AM, the bane for most metal AM processes, particularly laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), has been support structures. They have been a necessary evil since the process was invented, and they are one of the quickest ways to kill a compelling business case for AM.

Supports are the “scrap” of metal AM, and we all know that scrap is bad for any manufacturing process. It is something manufacturing engineers work hard to reduce and eliminate with conventional processes, and the same is true for AM. Supports increase material consumption, which adds cost, increases build time, which adds more cost and increases post-processing time, which also adds cost. Supports are a big cost multiplier that work against us, not for us.

The term “supports” is actually a misnomer. Supports do not actually support the overhanging or cantilevered features on a part as the name implies. In reality, they help anchor such features down to the build plate (or to another feature in the part) to ensure that these features do not warp or distort during the build. This warping or distortion is usually upward (in the + z direction), and with layers as thin as 20-40 microns, it does not take a lot of upward motion before collision with a recoater blade may occur—just ask any L-PBF technician or machine operator and they will have plenty of build failure stories to share (check out our #AMWTF series).

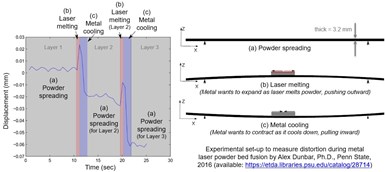

Figure 1. Experimental validation of warping and distortion that results from repeated heating and cooling during metal laser powder bed fusion (adapted from Alex Dunbar, Penn State, 2016)

As many people know now, the warping and distortion results from the residual stresses that accumulate during the build. The constant heating and cooling (i.e., thermal cycling) causes regions in the part to expand and contract (see Figure 1), which induces residual stresses in the metal AM part. The same thing happens during welding, which is why joints are stress-relieved after welding. Again, no surprises here, and while countless methods, tools and algorithms exist to try and avoid overhanging structures when designing a part, supports remain inherent to L-PBF.

Velo3D and now SLM Solutions have fundamentally changed the game though for L-PBF, eliminating the need for supports with their SupportFree and Free Float technology, respectively. This has always been within the realm of the possible; it just required a lot of time and energy (and money) to perfect the algorithms and software needed to analyze every feature on a part, identify the downward facing surfaces on each of these features and compute the appropriate process parameter settings for the laser scan pattern based on the angle of inclination for each surface on each feature of each layer for each part. Piece of cake, right?

Velo3D was among the first AM original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to offer this, and it was great to see them named as one of Most Innovative Manufacturing Companies in Fast Company—a possible first for an AM OEM to be named on their list. Nonetheless, what I did not fully appreciate until I was speaking with Mike Rogerson last month was how eliminating supports from the majority of metal parts completely changes the economics for manufacturing existing parts, as I have railed against time and again.

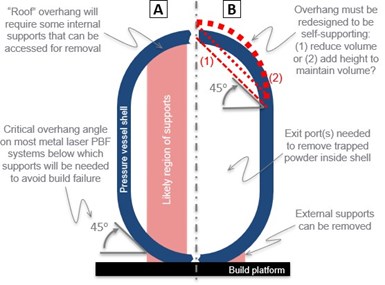

Figure 2. Challenges of making a simple pressure vessel using metal using laser powder bed fusion: original shell (A) as well as redesigned shell (B) to avoid overhangs using one of two possible solutions (1) and (2)

No supports means no scrap. It means no wasted material, no unnecessary build time and not nearly as much post-processing. It also means simpler geometries are easier to make, as well as more complex geometries. Take a pressure vessel, for example. They are relatively simple in terms of shape, but you could never replicate one of these easily with L-PBF processes that require supports, because a portion of the internal shell structure will likely exceed the critical overhang limit (see Figure 2). Redesigning the internal structure of a pressure vessel in order to eliminate overhangs that need supports requires extra engineering effort, time and cost, and it drives up risk—and good luck passing code; code cases for AM pressure vessels are still in development.

So while eliminating supports may sounds like a small thing, it is big for metal AM. It means that process substitution is exactly that—process substitution. Not redesign to make AM work. Thus, companies can spend their time and money qualifying an AM process and the associated material feedstocks, not re-engineering parts, and the uphill battle is no longer as steep.

Related Content

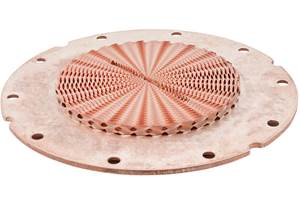

With Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM), Cooling Technology Is Advancing by Degrees

San Diego-based Fabric8Labs is applying electroplating chemistries and DLP-style machines to 3D print cold plates for the semiconductor industry in pure copper. These complex geometries combined with the rise of liquid cooling systems promise significant improvements for thermal management.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreDMG MORI: Build Plate “Pucks” Cut Postprocessing Time by 80%

For spinal implants and other small 3D printed parts made through laser powder bed fusion, separate clampable units resting within the build plate provide for easy transfer to a CNC lathe.

Read More3D Printed Cutting Tool for Large Transmission Part: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

A boring tool that was once 30 kg challenged the performance of the machining center using it. The replacement tool is 11.5 kg, and more efficient as well, thanks to generative design.

Read MoreRead Next

Crushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read More