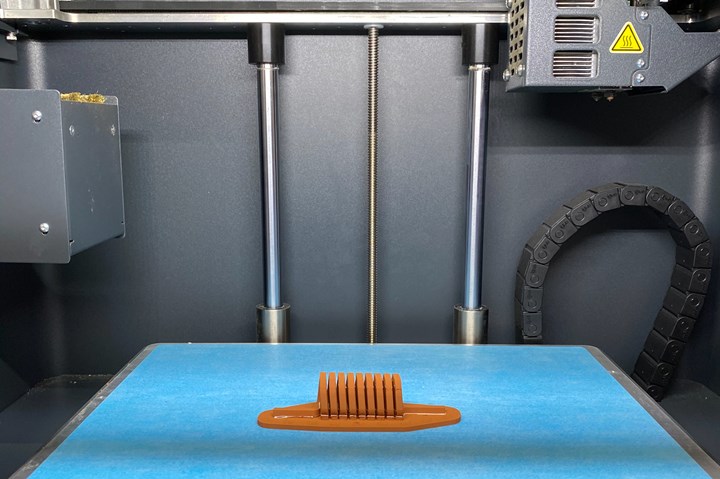

The Markforged Metal X 3D printing system is safe enough that RPG runs it in company president Robert Ginsburg’s office. Keeping the system locked in this office helps the company keep proprietary 3D printed customer parts secure.

RPG Industries Inc. is a machining job shop that has a number of different types of CNC machine tools on its shop floor, from EDM and abrasive waterjet to turning and milling. But visitors won’t find the primary equipment for its newest capabilities out on the shop floor with the rest of the machine tools — it’s kept in the company president’s office.

Robert Ginsburg, RPG’s founder and president, has always worked to ensure that his company stays ahead of the competition. He started the company as a wire EDM (electrical discharge machining) shop in the mid-90s when this technology was relatively new, eventually adding abrasive waterjet, sinker EDM, EDM drilling, milling and turning machines to the Tipp City, Ohio-based facility.

With his interest in such a wide array of manufacturing technologies, it may come as no surprise that Ginsburg felt drawn to additive manufacturing (AM). “3D printing really intrigued me,” he says. “You can design something on a computer, hit a button and the next day you have a functional part.” About eight years ago, he got a desktop polymer 3D printer from Afinia and started using it around the house, eventually bringing it into the shop to 3D print tooling. “I’ve always been a tinkerer. I enjoy the creative process,” he adds.

Beyond the desktop polymer 3D printer, Ginsburg was interested in adding metal additive manufacturing to the shop. He knew this capability would give his shop an edge by enabling it to print parts that can’t easily be produced by machining. But as he looked into it, he realized that most metal AM processes, such as powder bed fusion (PBF), involve the use and handling of metal powder, which wasn’t a good fit for RPG. The company wasn’t willing to make the additional investments required to manage the hazards of working with this raw material. He set aside the idea of adding metal AM capabilities to RPG, until he came across the Metal X metal 3D printer from Markforged.

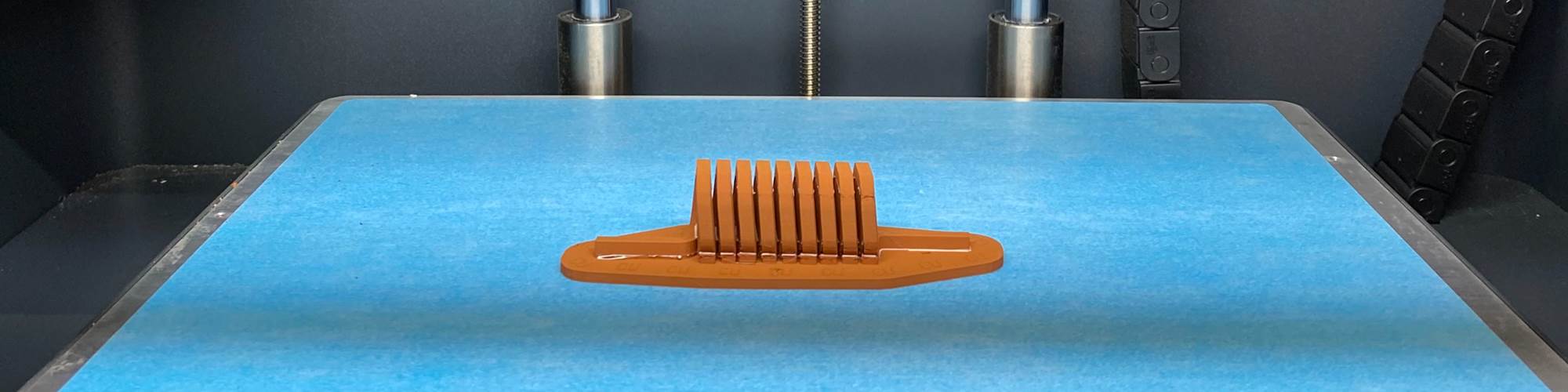

The Metal X uses a metal fused filament fabrication process that extrudes filaments carrying bound metal powder and a ceramic release material onto the machine’s print bed.

This system is well-suited to small, independent manufacturers like RPG because it uses a metal fused filament fabrication (FFF) process. Instead of loose metal powder, the machine prints with polymer filaments that contain bound metal powder and a ceramic release material. The metal filament is extruded onto the machine’s print bed to build an oversized part. After the print is complete, the part goes into another machine for a wash cycle that lasts about 12 hours. During this process, a solvent dissolves most of the polymer binding material.

The washed parts then go into a sintering oven for a little over 24 hours, where the remaining binder and ceramic supports are burned away and the part shrinks down to its final size. After sintering, some post-processing may be required, but Ginsburg says it’s minimal. “The parts are so close to net shape that very little secondary machining is required,” he notes.

Because the metal FFF process is so similar to the polymer FFF process used by desktop 3D printers, he says the learning curve for the Metal X wasn’t so steep. “I think it’s experience more than anything,” he says. “The more you do, the more you figure out how to slice the parts and orient them on the build sheet. It’s not difficult, but it becomes easier with trial and error.”

Living in a Material World

The system’s use of bound metal filament makes it easy for RPG to switch between materials. “I can run 17-4, and then within 15 to 20 minutes, I’m running copper, or vice versa,” Ginsburg says. He contrasts this with PBF machines, which are often dedicated to a single material because of the difficulty cleaning the previous powder out of the machine to switch to a new material. By contrast, the The Metal X makes the process of switching materials simple. “It’s just like doing it in a polymer-based machine or a traditional plastic printer,” Ginsburg says. This feature gives the shop flexibility to take on a wide range of work, which is essential as it works to grow its customer base in additive manufacturing.

Not only does the Metal X’s use of bound metal filament remove safety concerns inherent when using metal powders, it makes it easy for users to switch from one material to another. Metal filaments are produced by Markforged and are available in 17-4 PH stainless steel; H13, A2 and D2 tool steels; copper; and Inconel.

The metal filaments are produced by Markforged. Currently, the system can print parts in 17-4 PH stainless steel; H13, A2 and D2 tool steels; copper; and Inconel, all of which RPG has varying degrees of experience with. Of these materials, Ginsburg says that 17-4 is the most popular option for customers.

Lights Out

Another key factor that drew Ginsburg to metal 3D printing is its ability to run unattended. The printing, washing and sintering cycles might seem long compared to some subtractive processes such as turning, but they’re almost completely hands-off. He sees this as an important way forward for his shop because of the difficulty of finding skilled labor. “Having the lights out capability is just another revenue stream for the company that doesn’t add a lot of labor cost,” he explains.

“Having the lights out capability is just another revenue stream for the company that doesn’t add a lot of labor cost.”

Applications

Many of RPG’s metal 3D printing jobs involve one-off parts, such as this carburetor cover for a classic car. The original was broken and could not be repaired or replaced, and the part was cost-prohibitive to machine, making it an ideal application for the Metal X.

In the roughly three years that RPG has had the Metal X, the shop has found a number of applications for the system, one of the biggest being one-off parts. In order to help support this market, the shop has added a 3D scanner to provide reverse engineering services. One of the shop’s biggest successes in this area was a replacement part for a classic car. D&D Classic Automotive Restoration, a customer of RPG’s, was restoring a car from the 1930s when it discovered that the carburetor cap was broken. D&D couldn’t repair the part or buy a replacement, and it would have been cost prohibitive to machine a new one. RPG was able to use its 3D scanning capabilities to reverse engineer the part and 3D print it on the Metal X in 17-4 stainless steel.

RPG has also used the system to produce parts for the aerospace and defense

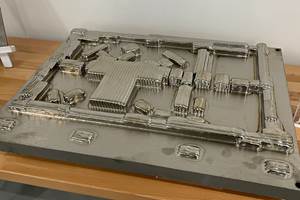

This nozzle was another metal 3D printing success for RPG. It was one of a series of nozzles in different sizes that RPG printed in 17-4 stainless. Ginsburg says it would have been difficult to produce this shape using a machining process.

industries. One of these jobs involved printing a series of nozzles in 17-4. They were round, hollow parts that had a series of “spokes” inside that would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to machine. “I honestly don’t know of a more effective way to produce it,” Ginsburg says. In total, the shop printed a few dozen in varying sizes. “I believe a majority of manufacturers would have no-quoted it based on the complexity,” he adds. But by batching the parts and producing them on the Metal X, RPG was able to cost-effectively turn each order around in about a week. “I don’t think traditionally machining the part would have been any quicker, and the cost would have been considerably higher,” he says.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the successes the shop has had so far with the Metal X, the machine is still underutilized. Ginsburg estimates that it runs 2 or 3 nights per month. He says the biggest challenge is educating its customer base on when to use 3D printing and how to design parts for it. The shop is working on some marketing initiatives in this area to help its current customers take full advantage of this capability.

Ginsburg has also identified a few areas of opportunity for the Metal X:

- 3D-printed molds. RPG does some moldmaking work on its EDM machines, and has a benchtop injection molding machine for proving out molds. Ginsburg believes that the shop could also use the Metal X to produce complex mold inserts.

- Medical prototyping. The low runs and intricate shapes of medical device prototyping would be a good fit for the system’s capabilities.

- 3D-printed copper electrodes. Markforged recently introduced a copper material for the Metal X, which could enable RPG to print complex electrodes for its sinker EDM machines.

- On-demand manufacturing marketplaces. RPG has been doing work through Xometry for a few years. Ginsburg estimates that this online manufacturing marketplace currently accounts for about 5% of the company’s business. However, none of that work is 3D printing work. He says that the platform isn’t currently set up to handle parts from Markforged machines. This presents an untapped market for the system because many of the jobs on these platforms are well-suited to 3D printing. “Most the work on Xometry we see is maybe three to ten parts, and that’s where the Metal X would shine,” he says.

Safety and Security

The system’s use of bound metal powder filament instead of loose powder eliminates many of the safety concerns inherent to other metal AM machines, making the Metal X is safe enough that Ginsburg can store the materials and printer in his office, and even run the printer there, while the wash station and sintering oven are out on the shop floor. He says he enjoys sharing an office with the 3D printer, and that it has the added benefit of providing an extra layer of security. “By keeping it in a locked office, it allows us to protect customers’ proprietary parts,” he explains. If a 3D printed part design is particularly secretive, he can assure the customer of being the only one who might see it.

Related Content

Zeda AM Production Plant in Ohio Now Open — Thoughts on the New Facility

73,000-square-foot metal powder bed fusion plant includes extensive machining capability plus separate operational models for serving medical versus other businesses.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Is Subtractive, Too: How CNC Machining Integrates With AM (Includes Video)

For Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing, succeeding with laser powder bed fusion as a production process means developing a machine shop that is responsive to, and moves at the pacing of, metal 3D printing.

Read MoreHow Norsk Titanium Is Scaling Up AM Production — and Employment — in New York State

New opportunities for part production via the company’s forging-like additive process are coming from the aerospace industry as well as a different sector, the semiconductor industry.

Read MoreTop 10 Additive Manufacturing Stories of 2023

Laser powder bed fusion, proprietary AM processes, machining and more made our list of top 10 articles and videos by pageviews this year.

Read MoreRead Next

FFF 3D Printing for Metal: Sintering Can Wait

Separating 3D printing from high-temperature processing is part of how the Markforged Metal X realizes a price less than established metal AM equipment.

Read MoreMetal AM System Revs Up Prototyping for Startup’s New Engine

The Desktop Metal Studio System demonstrates time and cost savings in prototyping and improving the parts for Lumenium’s IDAR engine.

Read MoreThe Promise of Lower-Cost Metal 3D Printing: 3 Views

Representatives of companies using the new Desktop Metal system—Caterpillar, Jabil and Lowes—describe their expected applications for this capability.

Read More