Material Freedom

A maker of engineered plastic components applies a 3D printer that uses the same granulate as molding machines.

If there is a battle of materials in bearings manufacturing, then Igus, the Cologne, Germany-based polymer bearing manufacturer is on team plastics. As opposed to most other bearings makers, Igus focuses exclusively on high-performance plastics for motion in industrial applications (what the company calls “motion plastics”). One of the distinctive aspects of Igus’s bearings is that they are self-lubricating and corrosion-resistant.

The company completes about 2 billion test cycles annually and has more than 200,000 end users around the globe. Tom Krause, product manager for Igus, says it started working with 3D printing in 2012 as a way to offer customers even more freedom in product design compared to making parts through molding. “We want to use the advantage of 3D printing to print parts that are complex to produce,” he says. 3D printing also allows for cost-effective production of unique parts or small series. Parts the company has made in this way include not only components for bearings, but also other parts where friction and wear are important, such as drive nuts or gears. The company even develops its own materials for these 3D printing applications.

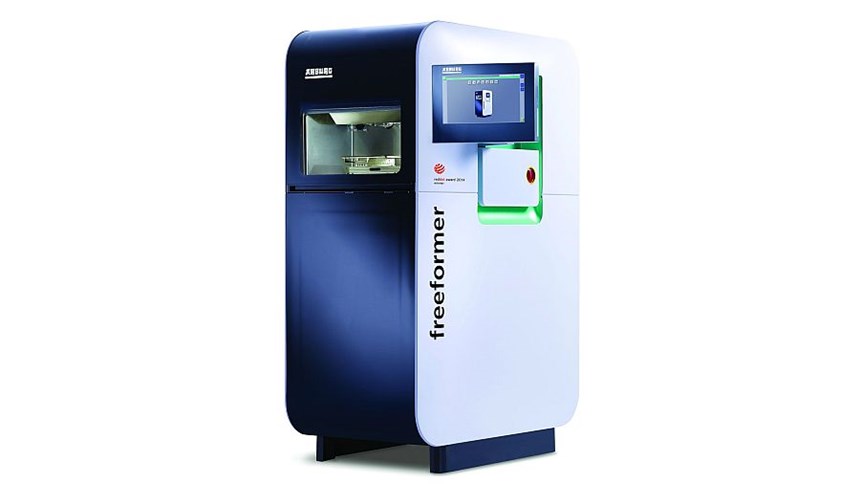

Particularly in light of this involvement in materials for 3D printing, Igus observed with interest a product introduction at the K Show in Düsseldorf, Germany, said to be the world’s largest trade fair for the plastics industry. At the 2013 event, injection molding machine maker Arburg introduced its Freeformer additive manufacturing system, which produces fully functional plastic parts without a mold from the same standard granulates used in injection molding. In this machine’s process—called AKF, the initials in German for Arburg Plastic Freeforming—standard granulates are melted in the same way they would be in an injection molding machine.

The AKF process makes use of 3D CAD files, which are read directly by the Freeformer. A nozzle closure with piezo technology then builds up the desired component layer by layer from plastic droplets to produce a three-dimensional part matching the CAD model. To create this geometry, the part under construction is moved under the nozzle by a component carrier with three or five axes.

Igus began to use the Freeformer in February 2015. Since then, it has put about 1,500 hours on the machine, the company says. Being able to use the same raw plastic as in most other plastic processing machines is a big advantage, says Krause. With the Freeformer, the company can use and try out a wider variety of plastics than with other printers.

“This raw material is much cheaper than the usual printing materials because with other printers, you need to have the plastic in a very special ‘shape,’ which makes it more expensive,” he says.

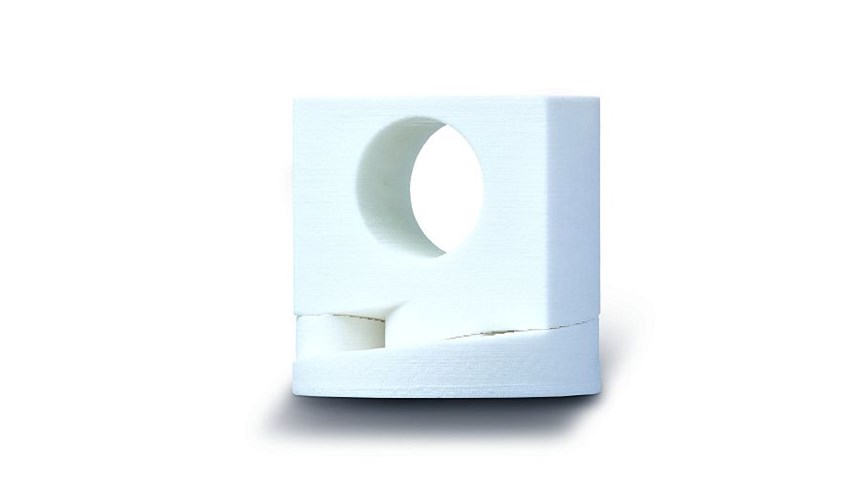

Thus far on the Freeformer, Igus has printed bearings, gears, sliders, drive-nuts and drive-screws. It has used both standard plastic granulates as well as its own 3D printing materials in the machine.

Krause says a big advantage of 3D printing in general is the ability to bypass expensive tooling for prototypes. The company can create new parts this way “much faster and more cost-effectively” than it could with previous prototyping methods. Some of the part geometries made this way are candidates for traditional molding. But, Igus also sometimes uses 3D printing to make parts that can’t be produced in any other way.

Related Content

6 Trends in Additive Manufacturing Technology at IMTS 2024

3D printers are getting bigger, faster and smarter. But don’t overlook the other equipment that the AM workflow requires, nor the value of finding the right supplier.

Read MoreActivArmor Casts and Splints Are Shifting to Point-of-Care 3D Printing

ActivArmor offers individualized, 3D printed casts and splints for various diagnoses. The company is in the process of shifting to point-of-care printing and aims to promote positive healing outcomes and improved hygienics with customized support devices.

Read MoreThis Drone Bird with 3D Printed Parts Mimics a Peregrine Falcon: The Cool Parts Show #66

The Drone Bird Company has developed aircraft that mimic birds of prey to scare off problem birds. The drones feature 3D printed fuselages made by Parts on Demand from ALM materials.

Read More3D Printing with Plastic Pellets – What You Need to Know

A few 3D printers today are capable of working directly with resin pellets for feedstock. That brings extreme flexibility in material options, but also requires greater knowledge of how to best process any given resin. Here’s how FGF machine maker JuggerBot 3D addresses both the printing technology and the process know-how.

Read MoreRead Next

Postprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read More3D Printed Polymer EOAT Increases Safety of Cobots

Contract manufacturer Anubis 3D applies polymer 3D printing processes to manufacture cobot tooling that is lightweight, smooth and safer for human interaction.

Read MoreAlquist 3D Looks Toward a Carbon-Sequestering Future with 3D Printed Infrastructure

The Colorado startup aims to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings, homes and city infrastructure with robotic 3D printing and a specialized geopolymer material.

Read More