High-Throughput Cell Segregates Additive, Subtractive Processes

The real value of building parts layer by layer isn't the potential to replace conventional, subractive machining, but to complement it.

The further additive manufacturing technology advances, the more it becomes apparent that the real value of building parts layer by layer isn’t the potential to replace conventional, subtractive machining, but to complement it. Indeed, some machine tool builders are offering hybrid models that combine additive and subtractive technology in a single platform. However, two industry suppliers claim that for high-production applications, separating the technologies and letting each type of machine do what it does best can be a better way to maximize overall throughput.

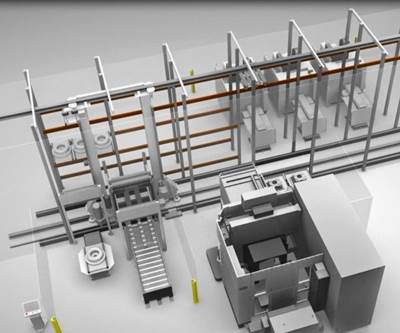

In keeping with that philosophy, Okuma America Corporation. has no immediate plans to offer its own additive equipment. That side of the equation falls to additive specialist RPM Innovations, Inc., a manufacturer of laser deposition machines. Meanwhile, members of Okuma’s Partners in THINC supplier network offer various options for linking the dedicated machines in an automated cell, whether the application calls for a single robot arm or a multi-pallet system like the one in the video below. “Making money in production applications is all about maximizing uptime,” says Wade Anderson, product specialist sales manager at Okuma. “The best way to make that happen is not to put both technologies in one machine, where one process has to wait for the other, but to link dedicated machines through an automated material handling system.”

The fact that one process is slower than the other strengthens the case for a cell in a high-production environment, says Robert Mudge, president and founder of RPM Innovations. Operating from CAD files, the company’s machines work by injecting metal powder directly into the melt pool created by a high-powered laser as it follows the contours of the workpiece, leaving deposits ranging from 0.005 to 0.04 inch thick and 0.04 to 0.16 inch wide. Although this technology opens new possibilities for creating difficult- or impossible-to-machine geometries in parts ranging to 7 feet tall and 5 feet wide, deposition rates range from a fraction of a cubic inch per hour to about 7 cubic inches per hour. At that rate, taking turns with a milling spindle can be impractical for parts produced in any significant volume, Mr. Mudge says. The opportunity cost of that strategy is particularly pronounced given the fact that cost-effectively machining additively produced geometries often requires equipment capable of complex, multi-axis contouring, or at least five-sided part access.

With loading and unloading automation, however, additive machines can contribute to a high-production process by working alongside their subtractive cousins without tying up milling capacity, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Mudge say. Maximizing both spindle and laser in-cycle time ensures the fastest possible process for the most common applications they foresee, such as building up worn turbine blade contours before machining them smooth, or additively producing and finish-machining automotive and aerospace parts that combine low weight and high strength for fuel efficiency. Further, there’s no reason why a hybrid cell couldn’t also churn out parts that require no additive processes at all, particularly if additive capacity is occupied at the time anyway.

A significant mismatch in processing speed isn’t their only argument for a cellular configuration. RPM’s laser deposition systems are designed to prevent oxidation of the metal powder by keeping oxygen levels below 10 parts per million (ppm) and dew point below -50°C in the workzone. Although shielding gas such as argon can prevent oxidation in a machine that combines additive and subtractive technologies, there’s still potential for increased consumable costs, Mr. Mudge says. Depending on the application, anywhere from 10 to 80 percent of the metal powder falls away from the deposition zone before it can be absorbed in the melt pool, he explains. If even a small portion of this material oxidizes, it can render the entire batch useless, he says. He adds that using a dedicated additive machine eliminates the risk of metal powder mixing with chips and coolant leftover from subtractive operations.

Another advantage of a cellular configuration is the ease with which other processes can be incorporated into the workflow, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Mudge say. Stress relief is a particular concern. Machining naturally imparts stress into workpiece material, Mr. Anderson explains—stress that, at some point, will release, potentially causing the final part to stretch and twist out of specification. Typically, processes like heat treating relieve this stress in a controlled, deliberate manner prior to finish-machining or other downstream operations. Whether contracted to an outside service or performed in-house, incorporating this operation won’t significantly disrupt a process in which workpieces move from one machine to another in an automated line, he says. The case is the same for cleaning, marking, inspection or any other downstream station.

However manufacturers choose to combine additive and subtractive technologies, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Mudge agree that the potential for time and cost savings can be dramatic. As a hypothetical example, they cite a job that involves machining a 200-pound part from a 2,000-pound forging. The ability to add certain features via laser deposition instead of machining them from stock could facilitate the use of a simpler, 400-pound forging instead. That translates to machining only 200 pounds of chips instead of 1,800. Put another way, incorporating additive technology would enable the same machining capacity to produce nine parts instead of one, regardless of a shop’s specific setup. However, for a high-volume manufacturer that prioritizes throughput, the best route may well be a cellular configuration that employs separate, dedicated machines to maximize the in-cycle time of both processes.

Related Content

Top 10 Additive Manufacturing Stories of 2023

Laser powder bed fusion, proprietary AM processes, machining and more made our list of top 10 articles and videos by pageviews this year.

Read MoreHow Electroplating Works for Polymer 3D Printed Parts

Baltimore-based RePliForm specializes in electroplating of 3D printed polymer parts for functional applications. This video explores how the process works, and potential benefits and uses for this technique.

Read MoreCopper, New Metal Printing Processes, Upgrades Based on Software and More from Formnext 2023: AM Radio #46

Formnext 2023 showed that additive manufacturing may be maturing, but it is certainly not stagnant. In this episode, we dive into observations around technology enhancements, new processes and materials, robots, sustainability and more trends from the show.

Read More3D Printed Cutting Tool for Large Transmission Part: The Cool Parts Show Bonus

A boring tool that was once 30 kg challenged the performance of the machining center using it. The replacement tool is 11.5 kg, and more efficient as well, thanks to generative design.

Read MoreRead Next

Okuma Engineer Offers Safety Tips for Hybrid Machine Tools

Shop air should be out of reach, but flood coolant is a friend, he says. The real challenge of hybrid machines right now is not safety procedures but software.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing and CNC Machining: Separate Together? Hear the Recorded Webinar

A maker of CNC machine tools and a maker of AM technology come together to describe integrating additive and subtractive into an efficient process for production.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read More