Optimized LPBF Reduces Cost Per Part by 90 Percent

Through a combination of laser powder-bed fusion, design and optimization technology, Betatype reduced the cost of an automotive part from more than $40 to less than $4.

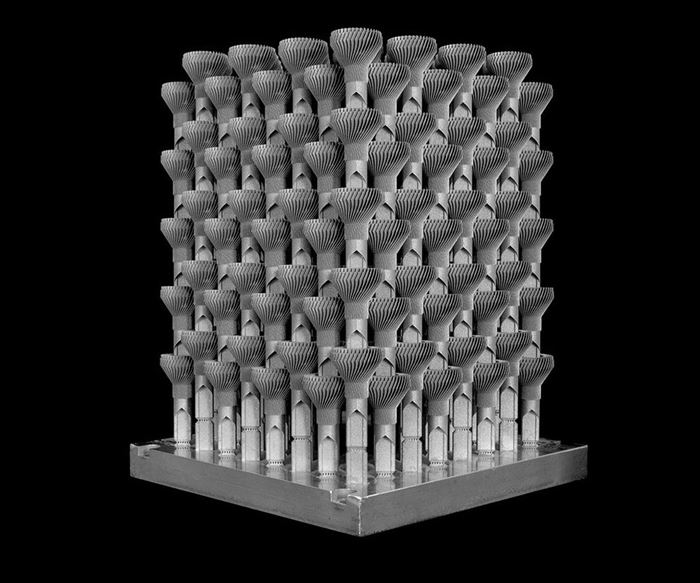

High volumes, productivity and cost-per-part are often cited as shortcomings of additive manufacturing (AM) for production applications in industries such as automotive. But AM process optimization that boosts productivity can reduce cost and support greater volumes. Betatype, a developer of AM optimization technology, recently worked on an automotive project using laser powder-bed fusion (LPBF) to produce 384 qualified metal parts in a single build, leveraging design and optimization strategies to reduce the cost-per-part.

Founded in 2012, Betatype has developed “Engine,” a data processing platform for managing and controlling multi-scale design. The technology can be applied to design complex parts that could not be easily built through traditional processes. Data processing also makes it possible to manage and optimize every tool path within each part, the company says, by shortening laser scan paths and delays. Geometry-driven control allows for the selection and application of laser parameters on an exposure to exposure level, enabling greater quality control and more efficient melting.

With the right part design, tool paths and parameters, additive manufacturing can be a more cost-effective method of production, as illustrated in Betatype’s manufacture of heatsinks for LED headlights. Typically, these components require comparatively large heatsinks which are often actively cooled. Betatype recognized that the specific geometry for these metal parts made them ideal for producing with LPBF.

By considering the LPBF process at the initial design stage of the component, Betatype was able to design a part with built-in support features, which allowed multiple headlight parts to be stacked on top of each other without the need for additional supports. Full stacking is often difficult with LPBF due to the thermal stresses involved in the layer process; by intelligently designing the structure to reduce thermal stresses, Betatype was able to make it a viable option with minimal thermal distortion. It was then possible to snap apart the finished parts by hand, without the need for further postprocessing.

For the collective 384 parts, Betatype was able to reduce build time from 444 hours to under 30 hours. Reducing the build time for these parts also reduced cost-per-part, from upwards of $40 to under $4.

The design of the part and supports enabled a series of parts to be “nested’” together to maximize the build volume, resulting in 384 parts being produced in one go within a single build envelope by Progressive Technology on an EOS 280M system.

Through specific control parameters, the exposure of the part in each layer was reduced to a single tool path, with minimal delays in between. This toolpath strategy, coupled with Betatype’s optimization algorithms and process IP, reduced the build time of each part from 1 hour to under 5 minutes per part, the company says.

For the collective 384 parts, Betatype was able to reduce build time from 444 hours to under 30 hours. Reducing the build time for these parts also reduced cost-per-part, from upwards of $40 to under $4.

The EOS M280 is a single-laser, medium-frame (SLMF) system; with a multi-laser, medium-frame 3D printer, Betatype’s optimization approach could reduce build time to less than 19 hours. Using one of these high-productivity systems would enable 19 times the productivity over a year of production per system, increasing volume from 7,955 parts to 135,168, Betatype says. With an installation of seven machines running this optimized process, volumes could approach 1 million parts per year, and those parts could be more functional and more cost-effective than those made conventionally.

Related Content

This 3D Printed Part Makes IndyCar Racing Safer: The Cool Parts Show #67

The top frame is a newer addition to Indycar vehicles, but one that has dramatically improved the safety of the sport. We look at the original component and its next generation in this episode of The Cool Parts Show.

Read MoreIndyCar's 3D Printed Top Frame Increases Driver Safety

The IndyCar titanium top frame is a safety device standard to all the series' cars. The 3D printed titanium component holds the aeroscreen and protects drivers on the track.

Read More8 Transformations 3D Printing Is Making Possible

Additive manufacturing changes every space it touches; progress can be tracked by looking for moments of transformation. Here are 8 places where 3D printing is enabling transformative change.

Read MoreWhat Holds AM Back in Automotive Production? GM Additive Lead Describes Advances Needed

“If AM were cheaper, we would be doing more of it,” says GM’s Paul Wolcott. Various important factors relate to cost. However, the driving factor affecting cost is speed.

Read MoreRead Next

Postprocessing Steps and Costs for Metal 3D Printing

When your metal part is done 3D printing, you just pull it out of the machine and start using it, right? Not exactly.

Read MoreBike Manufacturer Uses Additive Manufacturing to Create Lighter, More Complex, Customized Parts

Titanium bike frame manufacturer Hanglun Technology mixes precision casting with 3D printing to create bikes that offer increased speed and reduced turbulence during long-distance rides, offering a smoother, faster and more efficient cycling experience.

Read MoreCrushable Lattices: The Lightweight Structures That Will Protect an Interplanetary Payload

NASA uses laser powder bed fusion plus chemical etching to create the lattice forms engineered to keep Mars rocks safe during a crash landing on Earth.

Read More