3D printed plastic? Guess again.

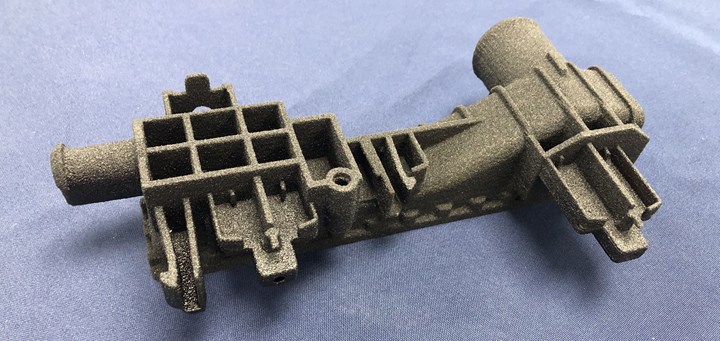

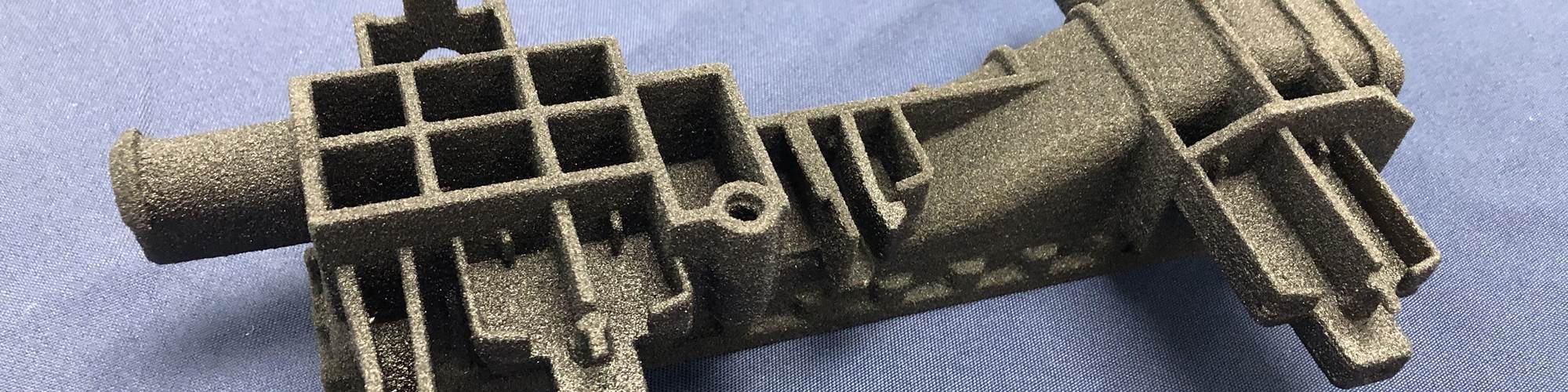

When I met with Mark and Brandon Lamoncha in an old Mitsubishi facility near Youngstown, Ohio, the part above was sitting on the conference table. Its rough surface registered as 3D printed, but I assumed it was made from polymer, maybe through a selective laser sintering (SLS) process. Admittedly I didn’t pay it much attention at all, because it didn’t match the profile of the work I was there to learn about: 3D printed sand tooling for foundry applications.

But then, partway through the conversation Mark handed me the part and made the reveal: This portion of a radiator cover was sand too.

“Normally if this was foundry sand and you squeezed it, it would just shatter,” he explained. “But with this infiltration process, you can make tooling out of it. You can make art. You can make a part that can be used.”

The surface of a resin-infiltrated sand print doesn’t need to stay rough; it can be coated to achieve a smooth, shiny finish.

The infiltration process he refers to is one recently patented by FreshMade3D, a Youngstown-area service bureau now with an outpost colocated in the same building as Humtown Additive, the 3D printing division of the Lamonchas’ Humtown Products. The two organizations have collaborated on a number of projects that infiltrate Humtown sand (3D printed on ExOne printers) with specialized FreshMade3D resins to give them the strength and durability to be used as end-use parts. The infiltrated sand items can be produced faster than injection molded parts by avoiding tooling, but they also have a notable advantage over plastic 3D printing: foundry sand (even the specialized kind used in sand printing) is still a cheaper feedstock than powdered polymer.

The combination of technologies has been used to produce vacuum- and thermoform tooling; columns and other architectural components; a full-sized statue replica currently on display at Ellis Island; and even a bowling ball that served as an early test of the technique and is still in use at a local alley.

Left: Dozens of green sand 3D printed brackets waiting to cleaned of loose sand and infiltrated with resin. Right: A completed face shield bracket ready for use.

Perhaps the highest volume application of resin-infiltrated sand thus far, though, turned out to be something right in front of my host’s nose: a face shield bracket. Like many 3D printing companies, Humtown too has spent time developing and manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE) in the fight against COVID-19. This bracket design is one result, and another potential use case for 3D printed sand strengthened with resin. You can read more about how Humtown Additive is innovating with sand 3D printing in this story.

A socially distanced conversation at Humtown Additive between me; Brandon Lamoncha, director of additive manufacturing; and Mark Lamoncha, president and CEO. The radiator cover is on the table, and Mark (right) is wearing Humtown’s sand 3D printed face shield bracket which fits onto a pair of safety glasses. Photo Credit: Cynthia Rogers, The Barnes Global Advisors

Related Content

-

In Casting and Molding, AM Simplifies Conventional Manufacturing

In new ways, additive processes are streamlining and enabling metal casting and plastic injection molding.

-

EOS Works With Phillips Federal, Austal USA to Develop CopperAlloy CuNi30 for US Navy Submarine Industrial Base

Using the copper-nickel alloy in combination with EOS’ platforms offers new design and production capabilities for U.S. Navy submarines, while also enabling the agency to limit global supply chain disruption because parts can be produced regionally, locally and on-demand.

-

New Equipment, Additive Manufacturing for Casting Replacement and AM's Next Phase at IMTS 2024: AM Radio #54

Additive manufacturing’s presence at IMTS – The International Manufacturing Technology Show revealed trends in technology as well as how 3D printing is being applied today and where it will be tomorrow. Peter Zelinski and I share observations from the show on this episode of AM Radio.

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)